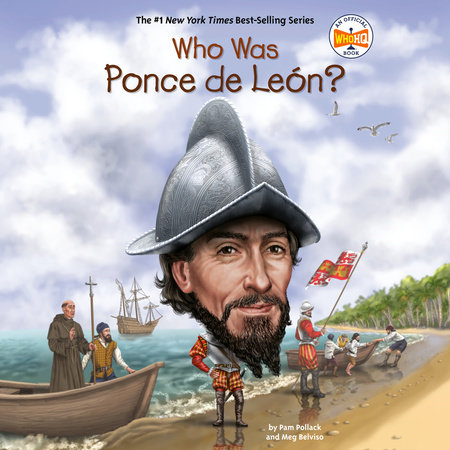

Who Was Ponce de León? Today, the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean is divided into two separate nations, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In the early 1500s, the whole island had been invaded and forced to become a colony of Spain. Hispaniola was ruled by a Spanish governor, Nicolás de Ovando. In 1508, Governor Ovando sent one of the Spanish men living on Hispaniola to explore the nearby island of Borinquén, which the Spanish called San Juan Bautista, but today is called Puerto Rico. The man’s name was Juan Ponce de León.

The Spanish governor considered the island of Hispaniola and the people there to be the property of his king and queen. The Spaniards had heard that there was gold in Borinquén, and they wanted all the gold they could get. Any they found had to be shared with King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Spain, but that still left plenty for a conquistador—or conqueror—to keep for himself.

In 1509, Juan Ponce de León returned to Hispaniola from Puerto Rico. Governor Ovando was eager to learn what he had seen and done there. Juan reported that he and his team of fifty men had founded a new settlement they called Caparra. The Taino people who already lived in Puerto Rico were no match for Juan’s soldiers and their guns.

Governor Ovando was very pleased with Juan’s report. The Spanish had already taken over the island of Hispaniola, enslaving the Indigenous people who lived there. Now, he hoped the Spanish could also rule Puerto Rico.

Governor Ovando rewarded thirty-five-year-old Juan by making him the first governor of Puerto Rico. He would pay him a good salary. He said that Juan could take a large piece of land in Puerto Rico and build a house on it. He could force the native people of the island to help him build it and work the land. The people of Puerto Rico did not have any choice in the matter.

Juan was thrilled with his new title and the riches that came with it: land, power, and gold. These were the reasons that Juan had left his home in Spain and traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to a world he had never seen before.

Chapter 1: A Young Page Juan Ponce de León was born in 1474 in Santervás del Campo, in the Valladolid province of northwest Spain. His father was Count Juan Ponce de León, a nobleman from a well-respected aristocratic family. The Ponce de Leóns were descended from the Visigoth kings of the Roman period in Spain.

We don’t know who Juan’s mother was, because his parents weren’t married. That wasn’t unusual for the Spanish nobles at that time. Juan’s father was said to have had twenty children from different mothers. By the time Juan was a young boy, an older relative, Rodrigo, was already famous for his bravery as a soldier. Rodrigo was named Duke of Cádiz in 1484.

Young Juan did not live with either of his parents. Like many children of noble families, he was sent to live with a relative at a young age. Juan’s guardian was named Pedro Nuñez de Guzman. He had the title of Knight Commander of the Order of Calatrava and was a personal friend of King Ferdinand. Pedro would teach Juan all the things he needed to know to grow up to be a knight like his famous relative, Rodrigo.

As a boy of noble blood, Juan did not go to school. He was taught by private tutors. Most children in Spain at that time didn’t read at all. Juan had access to Pedro’s private library, however, and he learned to read and write. He also learned how to behave at court with the king and queen. As a knight, he would one day serve the throne of Spain. He might very well meet the king and queen in person.

Spain was a Catholic country, and Juan learned the teachings of his church. He believed that anyone who wasn’t Catholic must be converted to Catholicism in order to go to heaven.

Juan’s education also focused on horseback riding and hunting. He learned to train hounds to chase animals like deer, boar, and even bears. He also trained birds of prey, including falcons and hawks, to fly away and then return to perch on his arm.

Juan practiced with all the weapons a knight of that time used. That meant learning to fight with a sword and hold a lance while riding on horseback. He also practiced shooting the arquebus, a gun that looked like a long rifle.

When Juan was still a boy, he began working as a page for his guardian, Pedro. A page was a young man who trained to be a knight by serving one. Juan knew that as a knight he would have to fight and maybe even die to defend the kingdom of Spain. He was ready to do that. In fact, he couldn’t wait to become a real knight. He longed for adventure, to see the world and win glory on the battlefield, as Rodrigo had.

And soon, he would get his chance.

Chapter 2: The Battle of Granada Juan was fourteen years old in 1488. He was ready to go to war and be the soldier that he’d trained to be his whole life.

For hundreds of years, the Catholic leaders of Spain wanted Spain to have only one religion—theirs. In the early eighth century, the Moors, who were Muslim, had invaded from North Africa and won control of the Iberian Peninsula in southwestern Spain. The Catholic Spaniards did not like any area being under the control of the Moors. The fighting between the two sides went on for centuries.

By 1488, when Juan was ready to join the fight, only one area remained under the control of the Moors: the emirate of Granada. The rulers of Spain, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, were united in wanting to drive the Moors out of this region. They gathered troops and weapons to overwhelm the Moors at Granada.

The emirate of Granada—the Moorish region—was able to hold out against the Spanish for so long because it was in the mountains and surrounded by towns and forts. Juan’s relative Rodrigo was already fighting against the Moors there. He was a war hero whom Queen Isabella described as the “mirror of chivalry.”

When Juan joined the Spanish soldiers fighting their way toward Granada, it was ruled by the young sultan Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII. His forces weren’t strong enough to fight against modern weapons like cannons and bombards, which fired heavy granite balls from far away. That meant the Spanish soldiers didn’t have to move in close to fight as they had in the past. They could also rely on their long arquebus rifles. Unlike earlier guns, these could be fired by a single man.

To complicate matters, the Moors were used to fighting only in mild weather. When winter set in, soldiers and commanders returned home. But under Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spanish soldiers were paid year-round and equipped for colder weather. That meant Juan fought year-round—and he fought so bravely that he came to the attention of the king and queen.

Juan and the other soldiers reached Granada in April 1491. They surrounded the city so that no one could get in or out or get food inside. Muhammad XII hoped to receive help from Egypt and Morocco, in northern Africa, but no help came. After eight months, the sultan surrendered Granada to Ferdinand and Isabella. He opened the doors of his city to them, saying, “These are the keys of this paradise.”

Muslims and Jews would later be given this choice: either convert to Christianity or leave Spain. Victory at Granada convinced the Spanish king and queen that they were superior to their enemies and that God wanted them to win. Spain was now a completely Catholic country. Because of their victory over the Moors, they believed they should go out and search for other lands to conquer and to spread their Catholic faith.

They would need conquistadors—from the Spanish word for conqueror—to explore new lands for them. These knights and soldiers would sail forth from Europe, opening trade routes and claiming land for their home countries. Ferdinand and Isabella thought Juan, now eighteen years old, was just the kind of conquistador they needed.

Copyright © 2022 by Pam Pollack and Meg Belviso. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.