Chapter One

MermaidsIn June 1990, Barbara Bush visited the campus of Wellesley College to perform the routine duty of delivering a commencement speech to that year’s graduating class. She was roughly eighteen months into her tenure as First Lady and was in the midst of a busy graduation season; she had already delivered remarks to graduates at the University of Pennsylvania and St. Louis University. Her appearance at Wellesley, an elite all-female school in the woods of eastern Massachusetts, was supposed to be the sort of choreographed assignment that she could carry out in between fundraising trips to Texas and White House events in Washington.

But Barbara had known that her Wellesley visit would be different. The students hadn’t wanted her to come.

The year had marked the dawn of a new decade, and a generation of young American women had been raised on the promise that they would benefit from the landmark political and cultural changes that had occurred during their lifetimes. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 had prohibited workplace and pay discrimination on the basis of sex. In 1973, Roe v. Wade established a constitutional right to abortion. The 1980s saw women enter the workforce at unprecedented levels, prompting new discussions about how to balance having a family and a career—and whether it was at all possible. So the First Lady’s trip to Massachusetts was overshadowed by a roiling debate over whether Barbara—then the sixty-four-year-old wife of a Republican president and a woman whose primary life achievements included supporting her family—deserved to deliver the Wellesley commencement address.

“Wellesley teaches that we will be rewarded on the basis of our own merit, not on that of a spouse,” read a petition that circulated among students protesting the First Lady’s speech. “To honor Barbara Bush as a commencement speaker is to honor a woman who has gained recognition through the achievements of her husband, which contravenes what we have been taught over the last four years at Wellesley.”

Barbara had not been their first choice. That privilege had gone to the Black novelist Alice Walker, who won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for The Color Purple, an exploration of Black womanhood, gender roles, sexual discovery, and resilience. American feminism was slowly beginning to expand its gaze from the white middle class to include women of color, but Walker was vocal in her belief that feminism—at least as it was understood, discussed, and marketed—had not been inclusive enough. She had coined the term “womanist” to make the point that feminism—at least as far as a generation of white women had defined it—largely excluded the experiences of women of color. Walker was a provocative and accomplished author who could challenge a graduating class primarily composed of middle-class white women, but she declined the invitation.

The invitation was repurposed and sent to the Bush White House, where it promptly sparked a debate about modern feminism that drew national attention. The graduates were trying to understand, really, the limits of what they were allowed to want. Was it a career? Was it a career and a marriage? Was it a career, a marriage, and children? This was the first generation to be introduced to the idea of “having it all,” a phrase that has, for decades, prompted endless searching discussions but no universal answer. (If you ask Jill Biden, a working mother and grandmother with a demanding schedule, what “having it all” means, she will look at you quizzically before answering, “I don’t think you can really have it all. You know, at least not at the same time. And I think I would never say that for myself.”)

The criticism over the invitation to Barbara was so widespread that even the president got involved. President George H. W. Bush could not resist defending his wife: “I think these young women can have a lot to learn from Barbara Bush and from her unselfishness and from her advocacy of literacy and of being a good mother and a lot of other things,” the president said, according to a front-page story in The New York Times that appeared in May 1990.

On graduation day, the First Lady appeared onstage at Wellesley with Raisa Gorbacheva, the wife of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who at the time was overseeing the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Their appearance was meant to telegraph a new sense of optimism that the Cold War would finally end.

Barbara wore a robe, her trademark string of pearls, and brick-red lipstick. Her white hair was rolled into a tuft of snowy curls. She understood that she wasn’t exactly the picture of modernity. She had dropped out of school after two years at Smith College to marry George Bush, a handsome navy warplane pilot who had narrowly survived a combat mission in September 1944. (They married in January 1945.) The couple moved to Texas and had six children, with Barbara watching over the brood as her husband built an oil business and, later, a career in politics.

Forty-five years later, she found herself speaking to a crop of young and idealistic graduates who had been conditioned to question the offerings of domesticity. Instead of trying to assure the young women that she was one of them, and instead of being defensive about her background and her decisions to marry rather than pursue a career, she honestly and elegantly drew contrasts between her generation and theirs.

“Now, I know your first choice for today was Alice Walker—guess how I know—known for The Color Purple,” she told the crowd. “Instead you got me, known for the color of my hair.”

The speech that followed was earthy and full of humor, delivered with the sly smiles and in-on-the-joke grimaces of a woman who understood what the crowd expected from her and who was intent on delivering something else.

She recounted a story by the author Robert Fulghum about a young pastor who created a game called Giants, Wizards, and Dwarfs for a group of unruly children. “You have to decide now,” the pastor instructed the children, “which you are . . . a giant, a wizard or a dwarf.”

As the children rushed to sort themselves into categories, the pastor felt a small girl tugging at his pants leg: “But where do the mermaids stand?” she asked. The pastor told her that mermaids didn’t exist, but the little girl protested, insisting that she was, indeed, a mermaid.

“She intended to take her place wherever mermaids fit in the scheme of things,” the First Lady told the graduates in the crowd. “Where do mermaids stand, all of those who are different, those who do not fit the boxes and the pigeonholes?”

There had been so much controversy surrounding the event that three major networks aired it live, an unusual occurrence for a First Lady’s speech. She urged the women in the crowd to embrace their passions, nurture their relationships, and prioritize their time with their families.

“At the end of your life, you will never regret not having passed one more test, winning one more verdict, or closing one more deal,” she told them. “You will regret time not spent with a husband, a child, a friend, or a parent.”

Americans who observed the speech that day saw a First Lady who used grit and grace to nod to a new generation and acknowledge that times were changing: “Somewhere out in this audience may even be someone who will one day follow in my footsteps and preside over the White House as the president’s spouse,” she said. “And I wish him well.”

When she was finished, the graduates got to their feet and cheered. The stakes had been high and the margin for error was slim, but it only took eleven minutes for the First Lady, whose very presence had been the subject of protest and ridicule, to disarm her audience. When Barbara arrived back at the White House, aides had strung up a banner to greet her home: a job wellesley done.

“You can see the winds of change in that crowd of women,” said Anita McBride, who served as chief of staff to Laura Bush and now studies the history of First Ladies. “That, for me, is really a signal for the modern age of the First Lady. Society was changing, the generations were changing, and they had different expectations for women’s roles.”

The role of First Lady is an unpaid position that bestows upon its holder no formal responsibilities, only the pressure of meeting the ever-shifting expectations of the president, his aides and allies, the American people, and a restive press corps. In biographies and memoirs, the women who have served the American people alongside their husbands have grappled with the responsibility and difficulty of occupying this rare space in government.

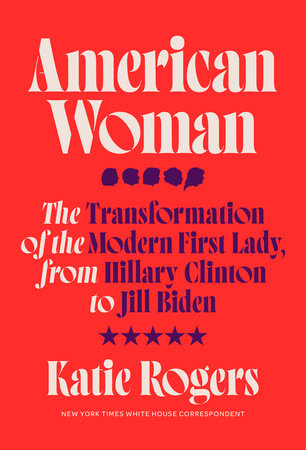

Copyright © 2024 by Katie Rogers. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.