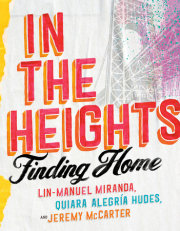

1A Multilingual Block in West PhillyDad was hurrying mom in English. “Let’s go, Virginia,” as he leaned against the tailgate sucking an unfiltered so hard I heard it crackle all the way on the stoop. Mom propped the screen door with her foot, ordering me to carry out boxes in snaps, gestures, and screams. And Titi Ginny was telling mom to pay dad no mind in Spanish. “Siempre tiene prisa,” she whispered with a tilted smile, turning dad’s impatience into a sweet little nothing.

My brat pack came to wave me off and started in on the obscene gestures whenever mom turned her back. Chien was first-generation Vietnamese. Ben and Elizabeth, first-gen Cambodian. Rowetha lost her Amharic after leaving Ethiopia. We all spoke English, unlike our parents, who all spoke different languages from one another. This was my West Philly crew, my pampers–to–pre-K alphabet soup. I assumed all blocks everywhere were like it—as many languages as sidewalk cracks, one boarded-up home for every lived-in, more gum wads than dandelions. But mom told me no, nature would reign at our new rental house on a horse farm.

Titi Ginny unlatched the screen so it slammed, and handed me a pastelillo grease-wrapped in paper towel. A snack for the drive. I wanted her to re-create our current layout in the new spot, to move next door so I could sneak across the alley and watch cartoons in her lazy boy. There was a spot between two pleather cracks, duct-tape repaired, where my butt fit perfectly. My Sunday morning throne. But mom said there were no alleys where we were moving, and no such thing as next door either. That gave me something to think about.

Anyway, Titi Ginny’s softball team was waiting in Fairmount Park and she had to be on second base in an hour. So she rolled down her driver’s side and promised to visit the farm, my big cousins in tow. Mary Lou, Cuca, Flor, Big Vic, Vivi, and Nuchi. She’d cram all their stinky teen butts in her backseat, and they’d see the country for the first time. “Bring Abuela and Tía Toña, oh, and Tía Moncha, too,” I said, marveling at the prospect of hanging with my fam outside of Philly. Titi Ginny turned the key and every version of dios-te-bendiga rolled off her tongue. There were a million ways to say god-bless in Spanish. Dios te cuide, dios te favoresca, dios te this and te that. There was only one way to say it in English, and you only said it after a sneeze. Then off she went before off we went.

Dad slammed the tailgate and mom teared up in the pleather passenger side. “Extrañaré a mi hermana.” Dad stayed quiet, probably didn’t understand. But I knew the Spanish word for missing someone sounded like the English word for strange. Sandwiched between them, I sensed mom’s worried profile. She had talked the move up for months, but saying goodbye to a sister was a whole ’nother thing.

“Then why do we have to move today? Can’t we finish out summer on the block?”

“Because, Quiara, I been stuck a city girl since I was eleven. But before that, before I came to Philly, I had a whole farm to myself. Mami gets to be with nature again, where she belongs, like in Puerto Rico.” And her tired eyes made room for a little spark.

How she told it, mom had been changing scenes all her life, same as geese veeing over the art museum. There was always a next stop full of new promise. Even Abuela’s memories about PR were made of a million places—towns, cities, and barrios. Too many to keep track. This time, I got to join mom’s migration.

Pulling away from the narrow block, the rearview showed my crew double-dutching and playing shoot-out. No final waves, hollers, or stuck-out tongues. Whatever’s the best language for saying bye, I’d flubbed it cuz the city already forgot me.

The horse farm was on a twisty road flanked by woods. Perky little hills worked a number on my bladder. Despite a strong midday sun, the road was all green shadow thanks to trees thick and tall as god’s fingers. My old block’s trees were like zoo elephants—one or two specimens stunted by a cement habitat. But this chaos of greenery had my heart calling dibs. Monster claws made of vine and bramble reached for our truck. Far as I had known, plants began in the soil and grew to the sky. But not here, where greenery grew sideways, diagonally, and downward. “We are your new brat pack,” the woods whispered, seeming mischievous as my old crew, and also like they wouldn’t tell on you.

When I got out of the pickup, I walked to the edge of the woods and stared. “Introduce yourself. Go talk to the trees,” mom said. I ventured in, ferns feathering my shins, and didn’t stop walking till I couldn’t see the house and the house couldn’t see me. Jack-in-the-pulpits were terrariums of rainwater and drowned flies. Mushrooms shriveled and swelled. A baby toad peed a puddle in my hand. In that moist wilderness, mine and mine alone, I recited a poem aloud. An original, from memory, about the Chuck Taylors that my dreams were made of. The trees listened close, gave a standing ovation. Their mossy velvet roots invited me to sit and felt so soft I almost forgot Titi Ginny’s lazy boy.

2Spanish Becomes a Secret; Language of the Dead“Please, mom? Can we go to Titi Ginny’s this weekend?”

“Ay, how many times do I have to say no?” Mom rested, sweating, against the hoe’s tall handle. Ribs heaving above spent lungs. All morning she had sliced the hoe’s blade downward, troughing and trenching a patch of earth out back. Now they reversed roles and the hoe supported her momentary repose. “Go cut me an eight-foot piece, entiendes?” She handed me a knot of twine. I found a measuring tape in dad’s workshop garage, and an exacto knife for cutting. Two important tools, I told myself, for an important task. When I returned with the measured and cut section, she told me to anchor one end in my fist. I held it firmly against the dirt, pink earthworms wriggling near my wrist. Mom lifted the twine’s loose end and walked a steady circular path using the rope as a tether, marking her course with a walking stick. In just minutes, she had etched a circle into the freshly turned soil. Its symmetry was flawless. Next came the compass, which I got to hold, as mom located north, east, west, south, and center. She marked each of the five directions with a river stone, conch shell, or raw quartz. The garden would be a living medicine wheel, she told me.

For the remainder of the weekend, whether baking bread or sweeping cobwebs from the ceiling, mom paused on the hour, headed out back, and jotted numbers in her marble composition book. “This column is time of day. This column is the sun’s position. This one, shadow length. So I know where to plant each herb. Back in Puerto Rico, Papi taught me. He couldn’t read or write, so his brain was his notebook. My job was to bring coffee to him while he farmed, then bring back the empty cup. Little by little, I observed his methods. He would share a tidbit about the plants, seasons, moon cycles. For a man who never stepped foot in a schoolroom, your abuelo was a genius.” A genius who died in Puerto Rico before I was born. The man and the island were mysteries to me, and the title Abuelo felt too familiar for, essentially, a stranger.

“How come he couldn’t read?”

“He knew a little. Mami taught Papi the basics. But when he was younger than you, Papi lost all his elders to a hurricane. An entire community carried out to sea and, whoosh, swallowed by the ocean. He was one of two children who survived. Grew up like a slave in poverty, but with his indigenous science knowledge.”

She compiled a notebook index of herbs and scooped me up for long drives to nurseries that might sell them. Angelica. Rosemary. Eucalyptus. Rue. Lemon balm. Yerba bruja. Basil (albahaca). Verdolaga (purslane). Peony. Artemisa (wormwood). Various types of mint. Parsley. Marjoram (mejorana). Hot peppers. Pazote. And many, many sages. Because of its strong personality and curative properties, sage was to be planted at center. Mexican sage. Purple sage. Pineapple sage. Lemon sage. Rooting young herbs in loose soil made mom glow with a radiance I’d never seen in Philly. Depending on the humidity, her hair might be a tall springy afro, pyramid down in loose curls, or lie smooshed beneath a bandana save a strand at the ears. As summer progressed, she darkened from new-penny bright to old-penny rich. But some things never changed: her ski slope nose, the overbite that emphasized her tiredest smile, and slender shoulders with enough soft to lean your head on.

Monday through Friday mom still left home early and came home late, the bone-tired breadwinner. I had no clue what she did in the city, but the long train ride home was standing-room-only as briefcases pummeled her knees. She returned soggy-limbed, a marionette whose strings had come loose. Mom’s curls and clothes that had been impeccable in the morning drooped off her brow, shoulders, and hips. She looked like a neglected laundry line. I was usually already in bed and only heard her entrance, the muffled footsteps in the hallways, the mattress’s sigh as it accepted her troubles. Often, a fight would suddenly energize her and I’d stare at the ceiling to mom and dad’s vitriolic screams.

Copyright © 2021 by Quiara Alegría Hudes. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.