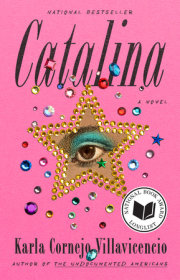

Chapter 1

Staten Island

August 1, 2019

If you ask my mother where she’s from, she’s 100 percent going to say she’s from the Kingdom of God, because she does not like to say that she’s from Ecuador, Ecuador being one of the few South American countries that has not especially outdone itself on the international stage—magical realism basically skipped over it, as did the military dictatorship craze of the 1970s and 1980s, plus there are no world-famous Ecuadorians to speak of other than the fool who housed Julian Assange at the embassy in London (the president) and Christina Aguilera’s father, who was a domestic abuser. If you ask my father where he is from, he will definitely say Ecuador because he is sentimental about the country for reasons he’s working out in therapy. But if you push them, I mean really push them, they’re both going to say they’re from New York. If you ask them if they feel American because you’re a little narc who wants to prove your blood runs red, white, and blue, they’re going to say No, we feel like New Yorkers. We really do, too. My family has lived in Brooklyn and Queens a combined ninety-seven years. My dad drove a cab back when East New York was still gang country, and he had to fold his body into a little origami swan and hide under his steering wheel during cross fires in the middle of the day while he ate a jumbo slice of pizza. Times have changed but my parents haven’t. My dad sees struggling bodegas and he says they’re fronts. For what? Money laundering. For whom? The mob. My mother wants my brother and me to wear pastels all year round to avoid being seen as taking sides in the little tiff between the Bloods and the Crips.

My parents are New Yorkers to the core. Despite how close we are, we’ve talked very little about their first days in New York or about their decision to choose New York, or even the United States, as a destination. It’s not that I haven’t asked my parents why they came to the United States. It’s that the answer isn’t as morally satisfying as most people’s answers are—a decapitated family member, famine—and I never press them for more details because I don’t want to apply pressure on a bruise.

The story as far as I know it goes something like this: My parents had just gotten married in Cotopaxi, Ecuador, and their small autobody business was not doing well. Then my dad got into a car crash where he broke his jaw, and they had to borrow money from my father’s family, who are bad, greedy people. The idea of coming to America to work for a year to make just enough money to pay off the debt came up and it seemed like a good idea. My father’s family asked to keep me, eighteen months old at the time, as collateral. And that’s what my parents did. That’s about as much as I know.

You may be wondering why my parents agreed to leave me as an economic assurance, but the truth is I have not had this conversation with them. I’ve never thought about it enough to ask. The whole truth is that if I was a young mother—if I was me as a young mother, unparented, ambitious, at my sexual prime—I think I would be thrilled to leave my child for “exactly a year,” as they said it would be, which is what the plan was. I never had to forgive my mom.

My dad? My dadmydadmydad was my earliest memory. He was dressed in a powder-blue sweater. He was walking into a big airplane. I looked out from a window and my dad was walking away and, in my hand, I carried a Ziploc bag full of coins. I don’t know. It’s been almost thirty years. It doesn’t matter anymore.

My parents didn’t come back after a year. They didn’t stay in America because they were making so much money that they became greedy. They were barely making ends meet. Years passed. When I was four years old, going to school in Ecuador, teachers began to comment on how gifted I was. My parents knew Ecuador was not the place for a gifted girl—the gender politics were too f***ed up—and they wanted me to have all the educational opportunities they hadn’t had. So that’s when they brought me to New York to enroll me in Catholic school, but no matter how hard they both worked to make tuition, they fell short. Then one day—I think I was in the fourth grade—the school bursar called me into his office and explained that there was an elderly billionairess who lived in upstate New York who had heard about me and was impressed. He told her my family was poor and might have to pull me from the school. (Okay, so in this scenario the tragedy would have been that I’d have to go to the local public school, which was not a great school, but just so we’re on the same page, I support public schools and I would have been fine.) So she came up with a proposition. She’d pay for most of my tuition if I kept up my grades and wrote her letters.

That was the first time in my life I’d have a benefactor, but it would not be my last. When I was at Harvard, a very successful Wall Street man who knew me from an educational NGO we both belonged to—he as a supporter, me as a supported—learned I was undocumented and could not legally hold a work-study job, so every semester he wrote me a modest check. In the notes section he cheekily wrote “beer money”—the joke being that I wouldn’t really drink until I was twenty-one—but every semester I used it for books, winter coats for those f***ing Boston winters, money I couldn’t ask my parents for because they didn’t have any to give. I wrote him regular emails about my life at Harvard and my budding success as a published writer. He was always appropriate and boundaried. I had read obsessively about artists since I was a kid and considered myself an artist since I was a kid so I didn’t feel weird about older, wealthy white people giving me money in exchange for grades or writing. It was patronage. They were Gertrude Stein and I was a young Hemingway. I was Van Gogh, crazy and broken. I truly did not have any racial anxieties about this, thank god. That kind of thing could really f*** a kid up.

I’m a New York City kid, but although the first five years of my time in America were spent in Brooklyn, if we’re going to be real, I’m from Queens. Queens is the most diverse borough in the city. This might sound like a romanticized ghetto painting, but when I walk through my neighborhood, a Polish child with a toy gun will shoot at my head and say the same undecipherable word over and over; a Puerto Rican kid will rap along to a song on his phone and turn it up as loud as necessary to make out the lyrics, even rapping along to some N-words; some Egyptian teenagers will refuse to move out of my way as I’m simply trying to cross the street; and some Mexican guys will invite me to join a pyramid scheme. But none of us will try to take any rights away from each other. We don’t have potlucks, but we live in peace. We go to the same street fairs.

The other boroughs are less diverse, but I found that the same thing is basically true. Except for one borough that I was always curious about—Staten Island, New York’s richest, whitest, most suburban borough. It is almost 80 percent white. By way of comparison, Brooklyn and Queens are just less than half white, the Bronx is 45 percent white, and even Manhattan is only 65 percent white. Staten Island is geographically isolated—you can’t take the subway there from the city—and, I don’t know, man, there isn’t a lot of shared goodwill between islanders and city residents. It’s not like we’re unaware. They’ve literally tried to secede from New York City and form their own city or join New Jersey. In June 1989, the New York State legislature gave Staten Island residents the right to decide on secession, and in November 1993, 65 percent of voters voted yes. Governor Mario Cuomo insisted that the referendum be approved by the state legislature, where it was defeated, but the desire continued to bubble just beneath the surface for years, so even after the world was rocked by Brexit, you had local island politicians posting on social media about how inspiring an event it was. Staten Island is the city’s most conservative borough, pretty reliably Republican, the only borough in New York City to go for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election. It’s also the borough where Eric Garner was killed in a choke hold at the hands of NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo. A Staten Island grand jury declined to indict Pantaleo for murder.

I learned about all of this later. But the first time Staten Island really entered my consciousness was when there were news reports about hate crimes against Latinx people when I was a kid. This was the only context in which Staten Island was mentioned on Spanish nightly news—Mexican immigrants as victims of hate crimes at the hands of young black men, a cruel reminder of the rift between our communities.

Copyright © 2020 by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.