Excerpted from the introduction by Dmitri Nabokov As a tepid spring settled on lakeside Switzerland in 1977, I was called from abroad to my father’s bedside in a Lausanne clinic. During recovery from what is considered a banal operation, he had apparently been infected with a hospital bacillus that severely lessened his resistance. Such obvious signals of deterioration as dramatically reduced sodium and potassium levels had been totally ignored. It was high time to intervene if he was to be kept alive.

Transfer to the Vaud Cantonal University Hospital was immediately arranged, and a long and harrowing search for the noisome germ began.

My father had fallen on a hillside in Davos while pursuing his beloved pastime of entomology, and had gotten stuck in an awkward position on the steep slope as cabin-carloads of tourists responded with guffaws, misinterpreting as a holiday prank the cries for help and waves of a butterfly net. Officialdom can be ruthless; he was subsequently reprimanded by the hotel staff for stumbling back into the lobby, supported by two bellhops, with his shorts in disarray.

There may have been no connection, but this incident in 1975 seemed to set off a period of illness, which never quite receded until those dreadful days in Lausanne. There were several tentative forays to his former life at the

hôtel Palace in Montreux, the majestic recollection of which floats forth as I read, in some asinine electronic biography, that the success of

Lolita “did not go to Nabokov’s head, and he continued to live in a

shabby Swiss hotel.” (Italics mine.)

Nabokov did begin to lose his own physical majesty. His six-foot frame seemed to stoop a little, his steps on our lakeside promenades became short and insecure.

But he did not cease to write. He was working on a novel that he had begun in 1975—that same crucial year: an embryonic masterpiece whose pockets of genius were beginning to pupate here and there on his ever-present index cards. He very seldom spoke about the details of what he was writing, but, perhaps because he felt that the opportunities of revealing them were numbered, he began to recount certain details to my mother and to me. Our after-dinner chats grew shorter and more fitful, and he would withdraw into his room as if in a hurry to complete his work.

Soon came the final ride to the Hôpital Nestlé. Father felt worse. The tests continued; a succession of doctors rubbed their chins as their bedside manner edged toward the grave- side. Finally the draft from a window left open by a sneezing young nurse contributed to a terminal cold. My mother and I sat near him as, choking on the food I was urging him to consume, he succumbed, in three convulsive gasps, to congestive bronchitis.

Little was said about the exact causes of his malady. The death of the great man seemed to be veiled in embarrassed silence. Some years later, when, for biographical purposes, I wanted to pin things down, all access to the details of his death would remain obscure.

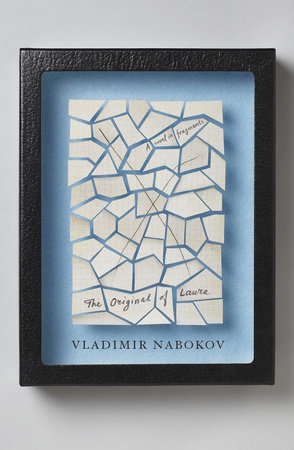

Only during the final stages of his life did I learn about certain confidential family matters. Among them were his express instructions that the manuscript of

The Original of Laura be destroyed if he were to die without completing it. Individuals of limited imagination, intent on adding their suppositions to the maelstrom of hypotheses that has engulfed the unfinished work, have ridiculed the notion that a doomed artist might decide to destroy a work of his, what- ever the reason, rather than allow it to outlive him.

An author may be seriously, even terminally ill and yet continue his desperate sprint against Fate to the last finish line, losing despite his intent to win. He may be thwarted by a chance occurrence or by the intervention of others, as was Nabokov many years earlier, on the way to the incinerator, when his wife snatched a draft of

Lolita from his grasp.

----

My father’s recollection and mine differed regarding the color of the impressive object that I, a child of almost six, distinguished with disbelief amid the puzzle-like jumble of buildings in the seaside town of Saint-Nazaire. It was the immense funnel of the

Champlain, which was waiting to transport us to New York. I recall its being light yellow, while Father, in the concluding lines of

Speak, Memory, says that it was white.

I shall stick to my image, no matter what researchers ferret from historical records of the French Line’s liveries of the period. I am equally sure of the colors I saw in my final onboard dream as we approached America: the varying shades of depressing gray that colored my dream vision of a shabby, low-lying New York, instead of the exciting skyscrapers that my parents had been promising. Upon disembarking, we also saw two differing visions of America: a small flask of Cognac vanished from our baggage during the customs inspection; on the other hand, when my father (or was it my mother? memory sometimes conflates the two) attempted to pay the cabbie who took us to our destination with the entire contents of his wallet—a hundred-dollar bill of a currency that was new to us—the honest driver immediately refused the bill with a comprehending smile.

In the years that had preceded our departure from Europe, I had learned little, in a specific sense, of what my father “did.” Even the term “writer” meant little to me. Only in the chance vignette that he might recount as a bedtime story might I retrospectively recognize the foretaste of a work that was in progress. The idea of a “book” was embodied by the many tomes bound in red leather that I would admire on the top shelves of the studies of my parents’ friends. To me, they were “appetizing,” as we would say in Russian. But my first “reading” was listening to my mother recite Father’s Russian translation of

Alice in Wonderland. We traveled to the sunny beaches of the Riviera, and thus finally embarked for New York. There, after my first day at the now-defunct Walt Whitman School, I announced to my mother that I had learned English. I really learned English much more gradually, and it became my favorite and most flexible means of expression. I shall, however, always take pride in having been the only child in the world to have studied elementary Russian, with textbooks and all, under Vladimir Nabokov.

My father was in the midst of a transition of his own. Having grown up as a “perfectly normal trilingual child,” he nonetheless found it profoundly challenging to abandon his “rich, untrammeled Russian” for a new language, not the domestic English he had shared with his Anglophone father, but an instrument as expressive, docile, and poetic as the mother tongue he had so thoroughly mastered.

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, his first English-language novel, cost him infinite doubt and suffering as he relinquished his beloved Russian—the “Softest of Tongues,” as he entitled an English poem that appeared later (in 1947) in the

Atlantic Monthly. Meanwhile, during the transition to a new tongue and on the verge of our move to America, he had written his last significant freestanding prose work in Russian (in other words, neither a portion of a work in progress nor a Russian version of an existing one). This was

Volshebnik (

The Enchanter), in a sense a precursor of

Lolita. He thought he had destroyed or lost this small manuscript and that its creative essence had been consumed by

Lolita. He recalled having read it to group of friends one Paris night, blue-papered against the threat of Nazi bombs. When, eventually, it did turn up again, he examined it with his wife, and they decided, in 1959, that it would make artistic sense if it were “done into English by the Nabokovs” and published.

That was not accomplished until a decade after his death, and the publication of

Lolita itself preceded that of its fore- bear. Several American publishers, fearing the repercussions of the delicate subject matter of

Lolita, had abstained. Convinced that it would remain forever a victim of incomprehension, Nabokov had resolved to destroy the draft, and it was only the intervention of Véra Nabokov that, on two occasions, kept it from going up in smoke in our Ithaca incinerator.

Eventually, unaware of the publisher’s dubious reputation, Nabokov consented to have an agent place it with Girodias’s Olympia Press. And it was the eulogy of Graham Greene that propelled

Lolita far beyond the trashy tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, inherited by Girodias from his father at Obelisk, and along with pornier Olympia stablemates, on its way to becoming what some have acclaimed as one of the best books ever written.

The highways and motels of 1940s America are immortalized in this proto–road novel, and countless names and places live on in Nabokov’s puns and anagrams. In 1961 the Nabokovs would take up residence at the Montreux Palace and there, on one of their first evenings, a well-meaning maid would empty forever a butterfly-adorned gift wastebasket of its contents: a thick batch of U.S. road maps on which my father had meticulously marked the roads and towns that he and my mother had traversed. Chance comments of his were recorded there, as well as names of butterflies and their habitats. How sad, especially now when every such detail is being researched by scholars on several continents. How sad, too, that a first edition of

Lolita, lovingly inscribed to me, was purloined from a New York cellar and, on its way to the digs of a Cornell graduate student, sold for two dollars.

Copyright © 2009 by Dmitri Nabokov. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.