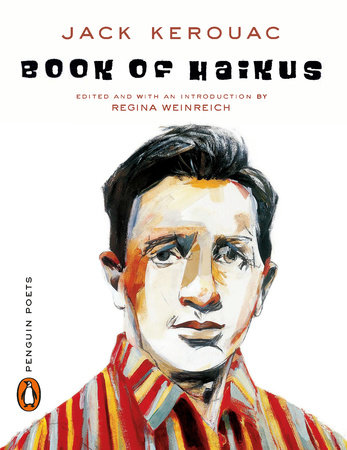

PENGUIN BOOKS

BOOK OF HAIKUS

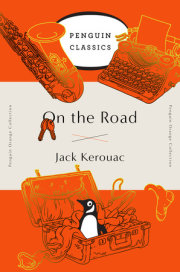

JACK KEROUAC was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, the youngest of three children in a Franco-American family. He attended local Catholic and public schools and won a football scholarship to Columbia University in New York City, where he met Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. His first novel, The Town and the City, appeared in 1950, but it was On the Road, first published in 1957, that made Kerouac one of the most controversial and best-known writers of his time. Publication of his many other books followed, among them The Subterraneans, Big Sur, and The Dharma Bums, in which he describes his discovery of haiku. Kerouac’s books of poetry include Mexico City Blues, Scattered Poems, Pomes All Sizes, Heaven and Other Poems, and Book of Blues. Kerouac died in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven.

REGINA WEINREICH teaches in the Department of Humanities and Sciences at the School of Visual Arts in New York and has published widely in periodicals including The New York Times, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Village Voice, and in the literary journals The Paris Review and Five Points. She is the author of Kerouac’s Spontaneous Poetics: A Study of the Fiction. She was a writer on the documentary The Beat Generation: An American Dream and a producer/director of Paul Bowles: The Complete Outsider.

by Jack Kerouac

the town and the city

the scripture of the golden eternity

some of the dharma

old angel midnight

good blonde and others

pull my daisy

trip trap

pic

the portable jack kerouac

selected letters: 1940–1956

selected letters: 1957–1969

atop an underwood

orpheus emerged

POETRY

mexico city blues

scattered poems

pomes all sizes

heaven and other poems

book of blues

THE DULUOZ LEGEND

visions of gerard

doctor sax

maggie cassidy

vanity of duluoz

on the road

visions of cody

the subterraneans

tristessa

lonesome traveller

desolation angels

the dharma bums

book of dreams

big sur

satori in paris

Jack Kerouac

BOOK

OF

HAIKUS

Edited and with an Introduction by

Regina Weinreich

Then I’ll invent

The American Haiku type:

The simple rhyming triolet:—

Seventeen syllables?

No, as I say, American Pops:—

Simple 3-line poems

Reading Notes 1965

Introduction: The Haiku Poetics of Jack Kerouac

The American writer Jack Kerouac is mostly known as a prose fiction stylist. He is famous for his bestselling novel On the Road and for having spawned the Beat Generation. For some, images of rebellious hipsters come to mind, as well as a beat determination not to revise, first thought best thought. But careful readers of Kerouac’s prose recognize that within the ragged, circular, soulful cadences for which his writing is at once criticized, imitated and revered is the rhythmic phrasing of poetry.

Among the literati who knew him best, Jack Kerouac was a poet supreme who worked in several poetry traditions, including sonnets, odes, psalms, and blues (which he based on blues and jazz idioms). He also successfully adapted haiku into English, his “American haikus.”1 “‘Haiku,’” he wrote, “was invented and developed over hundreds of years in Japan to be a complete poem in seventeen syllables and to pack in a whole vision of life in three short lines.” Finding that Western languages cannot adapt themselves to the “fluid syllabillic Japanese,” he sought to redefine the genre:

“I propose that the ‘Western Haiku’ simply say a lot in three short lines in any Western language. Above all, a Haiku must be very simple and free of all poetic trickery and make a little picture and yet be as airy and graceful as a Vivaldi Pastorella. Here is a great Japanese Haiku that is simpler and prettier than any Haiku I could ever write in any language:—

A day of quiet gladness,—

Mount Fuji is veiled

In misty rain. (Bashō) (1644–1694)

Thus, in this tradition, Kerouac wrote:

Birds singing

in the dark

Rainy dawn

Kerouac composed this and hundreds more haiku in notebooks dated from 1956 to 1966. These small, bound notebooks—the kind he could press into his checkered lumberman’s shirt pocket and carry around anywhere for fresh and spontaneous entries—contain a huge cache of his three-line jottings, a mother lode, so to speak, from which he selected what would comprise his Book of Haikus, a collection he urged Lawrence Ferlinghetti to publish in 1961. Five Working Notebooks dated 1961–1965 are another source of haiku, and more were embedded in novels, letters, or published in small literary magazines. Twenty-six, some chosen for a 1964 anthology of American verse edited by his Italian translator, Fernanda Pivano, were published posthumously in 1971 by City Lights in Scattered Poems. A manuscript page (Berg Collection of the New York Public Library) indicates Kerouac’s intentions.

Jack Kerouac was not the first American poet to experiment in haiku aesthetics. Before him, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Amy Lowell, and Wallace Stevens all created haiku-inspired verse. It was not until after the Second World War that a “rigorous and informed attention to the genre”2 arose, with the first volume of R. H. Blyth’s four-volume Haiku appearing in 1949, bringing the classical traditions of haiku and Zen to the West.

Kerouac turned to Buddhist study and practice after his “road” period, from 1953 until 1956, in the lull between the writing of the seminal On the Road in 1951,2 and its publication in 1957—that is, before fame changed everything. When he finished The Subterraneans in the fall of 1953, fed up with the world after the failed love affair on which the book was based, he picked up Thoreau and fantasized a life separate from civilization. Then he happened upon Asvaghosha’s The Life of Buddha and immersed himself in Zen study.

Kerouac began his genre-defying book Some of the Dharma in 1953 as a collection of reader’s notes on Dwight Goddard’s The Buddhist Bible; the endeavor grew into a massive compilation of spiritual material, meditations, prayers, and haiku, a study of his musings on the teaching of Buddha. By 1955, while living in North Carolina with his sister, he worked on two other Buddhist-related texts: Wake Up, his own biography of the Buddha, and Buddha Tells Us, translations of “works done by great Rimbauvian Frenchmen at the Abbeys of Tibet,” what he refers to in his letters as “a full length Buddhist Handbook.”

Haiku came to the West Coast poets through Gary Snyder. Inspired by D. T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism (1927) in the fall of 1951, Snyder spent the early ’50s traveling in Japan, studying and practicing Zen Buddhism. Philip Whalen and Lew Welch became avid haiku practitioners through his influence. Kerouac, Ginsberg, Snyder, and Whalen spent time together in Berkeley in 1955 talking, drinking, and trading their own versions of Blyth’s haiku translations, which they were reading in all four volumes. Through Blyth’s translations and his extraordinary commentary on the Japanese works, Kerouac found emotive and aesthetic sympathies. Even though he attempted to meditate, wrote a sutra, “The Scripture of the Golden Eternity” (1956) at Gary Snyder’s behest, and thought of his entire oeuvre, his Legend of Duluoz, as a “Divine Comedy” based on Buddha,3 Buddhism stayed a literary concern for him, not a meditative or spiritual practice, as it was for Snyder and Whalen. Later, when he told Ted Berrigan in his 1968 Paris Review interview he was a serious Buddhist, but not a Zen Buddhist, the distinction was to separate his interest from the prevalent scholarly study of dogma in favor of Buddhist essence.4 The practice of haiku, however, persisted throughout his life, becoming an important medium for rendering the Beat ideal of “shapely mind,” and for crafting an American Mysticism in the manner of Thoreau. For a new generation of poets, Kerouac ended up breaking ground at a pioneering stage of an American haiku movement.

Finding these haiku was a bit like extracting gold from baser metals, so embedded were many of them (nearly 1,000) in blocks of prose, scribble, and even street addresses. Many reappear throughout his work, because Kerouac recycled his haiku, using them in different ways.

Traditional haiku collections are organized by season or subject, but that did not seem an appropriate way to present Kerouac’s haiku. Part I of this volume is comprised of haiku he selected himself. The chronological organization of the haiku in Part II seemed the best way to give a sense of the evolution of the work, as well as to see each poem in its own light. Handy for this approach, Kerouac, in a 1963 journal, divided up his life according to the seasonal haiku reference, and so, following his idea, I have taken Spring and Summer as the period before the publication of On the Road, Autumn and Winter as after, in his later years.5

This book endeavors to include examples of the entire range of Kerouac’s haiku—those which he selected for publication (The Book of Haikus found in a black folder so named) and poems in those subcategories by which he experimented in haiku possibilities: the philosophical “pops” as well as the angry, emotionally blunt “beat generation haikus.” As with all of Kerouac’s work in prose and poetry, process is key to his search for more refined language.

Allen Ginsberg spoke perhaps hyperbolically of Kerouac as the “only master of the haiku: He’s the only one in the United States who knows how to write haiku . . . [he] talks that way, thinks that way.”6 What Kerouac “got” perhaps more than any other Beat poet working in this genre was the rendering of a subject’s essence, and the shimmering, ephemeral nature of its fleeting existence. This sensitivity to impermanence appears again and again in his work, from The Town and the City, constructed around the death of the father, through The Book of Dreams, which evokes the frail individual beset with a harsh, indifferent society, at times succumbing, defeated.

One of Kerouac’s classic haiku images is of a sole animate entity in a wide, cavernous expanse:

The windmills of

Oklahoma look

In every direction

And, from a 1960 notebook:

One flower

on the cliffside

Nodding at the canyon

That isolated being—here “look[ing]” or “nodding”—is the quintessential Kerouacean persona seen again and again in his Legend of Duluoz.

Seeking visual possibilities in language, Kerouac combined his spontaneous prose with sketching, a technique suggested to him by Ed White, a friend during his Columbia University days in the late ’40s: Why don’t you sketch in the streets like a painter but with words?

“‘Keep the eye STEADILY on the object,’ for haiku,” he exhorted himself in his notebooks. “WRITE HAIKUS THEN PAINT THE SCENE DESCRIBING THEM!” He also likened good haiku to good painting. The best haiku gave him “the sensation I get looking at a great painting by Van Gogh, it’s there & nothing you can say or do about it, except look in dismay at the power of looking.”

Kerouac also recognized the purposeful caesura or cut of Japanese haiku as key to its sound and sense. Quoting Shakespeare in a 1963 Notebook, Kerouac wrote: “birds sit brooding in the snow’ (combining the thought as well as the sound of the ellipse of a JAP haiku) always wondered where did he get that sound? & always think, that’s what I like about S, where he revels in the great world night.” The extraordinary juxtapositions often noted in Kerouac’s sketched prose—in Visions of Cody (written in 1951 and 1952, a portion published in 1959 as Visions of Neal), Doctor Sax (written in July 1952, published in 1959), and “October in the Railroad Earth,” (1952)—especially evoke haiku spirit, even before he was fully immersed in composing haiku.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.