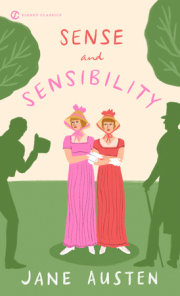

Chapter IThe family of Dashwood had long been settled in Sussex.Their estate was large, and their residence was at Norland Park,in the centre of their property, where, for many generations,they had lived in so respectable a manner, as to engagethe general good opinion of their surrounding acquaintance.The last owner but one of this estate, was a single man, who livedto a very advanced age, and who, for many years of his life,had a constant companion and housekeeper in his sister.But her death, which happened ten years before his own,produced a great alteration in his home; for, to supplyher loss, he invited and received into his house the familyof his nephew Mr. Henry Dashwood, the legal inheritorof the Norland estate, and the person to whom he intendedto bequeath it. In the society of his nephew and niece,and their children, the old Gentleman's days werecomfortably spent. His attachment to them all increased.The constant attention of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Dashwoodto his wishes, which proceeded not merely from interest,but from goodness of heart, gave him every degree of solidcomfort which his age could receive; and the cheerfulnessof the children added a relish to his existence.

By a former marriage, Mr. Henry Dashwood had oneson: by his present lady, three daughters. The son,a steady respectable young man, was amply providedfor by the fortune of his mother, which had been large,and half of which devolved on him on his coming of age.By his own marriage, likewise, which happened soon afterwards,he added to his wealth. To him, therefore, the successionto the Norland estate was not so really important as tohis sisters; for their fortune, independent of what mightarise to them from their father's inheriting that property,could be but small. Their mother had nothing, and theirfather only seven thousand pounds in his own disposal;for the remaining moiety of his first wife's fortune wasalso secured to her child, and he had only a life interestin it.

The old Gentleman died: his will was read, andlike almost every other will, gave as much disappointmentas pleasure. He was neither so unjust, nor so ungrateful,as to leave his estate from his nephew;—but he left it to himon such terms as destroyed half the value of the bequest.Mr. Dashwood had wished for it more for the sake of hiswife and daughters than for himself or his son;—but tohis son, and his son's son, a child of four years old,it was secured, in such a way, as to leave to himselfno power of providing for those who were most dearto him, and who most needed a provision by any chargeon the estate, or by any sale of its valuable woods.The whole was tied up for the benefit of this child, who,in occasional visits with his father and mother at Norland,had so far gained on the affections of his uncle,by such attractions as are by no means unusual in childrenof two or three years old; an imperfect articulation,an earnest desire of having his own way, many cunning tricks,and a great deal of noise, as to outweigh all the valueof all the attention which, for years, he had receivedfrom his niece and her daughters. He meant not tobe unkind, however, and, as a mark of his affectionfor the three girls, he left them a thousand pounds a-piece.

Mr. Dashwood's disappointment was, at first, severe;but his temper was cheerful and sanguine; and he mightreasonably hope to live many years, and by living economically,lay by a considerable sum from the produce of an estatealready large, and capable of almost immediate improvement.But the fortune, which had been so tardy in coming, was hisonly one twelvemonth. He survived his uncle no longer;and ten thousand pounds, including the late legacies,was all that remained for his widow and daughters.

His son was sent for as soon as his danger was known,and to him Mr. Dashwood recommended, with all the strengthand urgency which illness could command, the interestof his mother-in-law and sisters.

Mr. John Dashwood had not the strong feelings of therest of the family; but he was affected by a recommendationof such a nature at such a time, and he promised to doevery thing in his power to make them comfortable.His father was rendered easy by such an assurance,and Mr. John Dashwood had then leisure to consider howmuch there might prudently be in his power to do for them.

He was not an ill-disposed young man, unless tobe rather cold hearted and rather selfish is to beill-disposed: but he was, in general, well respected;for he conducted himself with propriety in the dischargeof his ordinary duties. Had he married a more amiable woman,he might have been made still more respectable than hewas:—he might even have been made amiable himself; for hewas very young when he married, and very fond of his wife.But Mrs. John Dashwood was a strong caricature of himself;—more narrow-minded and selfish.

When he gave his promise to his father, he meditatedwithin himself to increase the fortunes of his sistersby the present of a thousand pounds a-piece. He thenreally thought himself equal to it. The prospect of fourthousand a-year, in addition to his present income,besides the remaining half of his own mother's fortune,warmed his heart, and made him feel capable of generosity.—"Yes, he would give them three thousand pounds: it wouldbe liberal and handsome! It would be enough to makethem completely easy. Three thousand pounds! he couldspare so considerable a sum with little inconvenience."—He thought of it all day long, and for many days successively,and he did not repent.

No sooner was his father's funeral over, than Mrs. JohnDashwood, without sending any notice of her intention to hermother-in-law, arrived with her child and their attendants.No one could dispute her right to come; the house washer husband's from the moment of his father's decease;but the indelicacy of her conduct was so much the greater,and to a woman in Mrs. Dashwood's situation, with onlycommon feelings, must have been highly unpleasing;—but in her mind there was a sense of honor so keen,a generosity so romantic, that any offence of the kind,by whomsoever given or received, was to her a sourceof immoveable disgust. Mrs. John Dashwood had neverbeen a favourite with any of her husband's family;but she had had no opportunity, till the present,of shewing them with how little attention to the comfortof other people she could act when occasion required it.

So acutely did Mrs. Dashwood feel this ungraciousbehaviour, and so earnestly did she despise herdaughter-in-law for it, that, on the arrival of the latter,she would have quitted the house for ever, had not theentreaty of her eldest girl induced her first to reflecton the propriety of going, and her own tender love for allher three children determined her afterwards to stay,and for their sakes avoid a breach with their brother.

Elinor, this eldest daughter whose advice wasso effectual, possessed a strength of understanding,and coolness of judgment, which qualified her,though only nineteen, to be the counsellor of her mother,and enabled her frequently to counteract, to the advantageof them all, that eagerness of mind in Mrs. Dashwoodwhich must generally have led to imprudence. She hadan excellent heart;—her disposition was affectionate,and her feelings were strong; but she knew how to governthem: it was a knowledge which her mother had yet to learn;and which one of her sisters had resolved never to be taught.

Marianne's abilities were, in many respects,quite equal to Elinor's. She was sensible and clever;but eager in everything; her sorrows, her joys, could haveno moderation. She was generous, amiable, interesting: shewas everything but prudent. The resemblance betweenher and her mother was strikingly great.

Elinor saw, with concern, the excess of hersister's sensibility; but by Mrs. Dashwood it was valuedand cherished. They encouraged each other now in theviolence of their affliction. The agony of griefwhich overpowered them at first, was voluntarily renewed,was sought for, was created again and again. They gavethemselves up wholly to their sorrow, seeking increaseof wretchedness in every reflection that could afford it,and resolved against ever admitting consolationin future. Elinor, too, was deeply afflicted; but stillshe could struggle, she could exert herself. She couldconsult with her brother, could receive her sister-in-lawon her arrival, and treat her with every proper attention;and could strive to rouse her mother to similar exertion,and encourage her to similar forbearance.

Margaret, the other sister, was a good-humoredwell-disposed girl; but as she had already imbibeda good deal of Marianne's romance, without havingmuch of her sense, she did not, at thirteen, bid fairto equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life.

Copyright © 2014 by Jane Austen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.