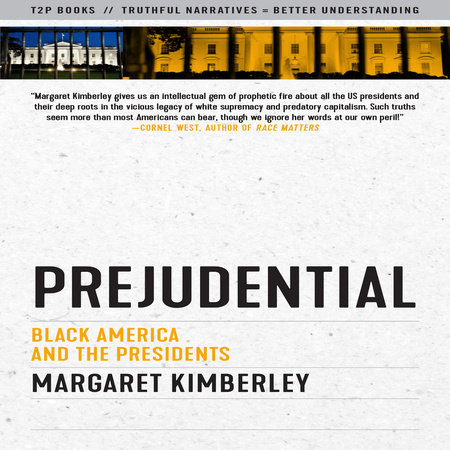

Author's Preface"In 1956, I shall not go to the polls. I have not registered. I believe that democracy has so far disappeared in the United States that no 'two evils' exist. There is but one evil party with two names, and it will be elected despite all I can do or say." — W. E. B. Du Bois, 1956

Once upon a time there were millions of people living on a continent. They were invaded by people from a distant part of the world. These newcomers killed them via military attacks, infectious diseases, and outright theft of their lands. The invaders also kidnapped other human beings from yet another part of the world and enslaved them on the stolen land. More than two hundred years after the invaders appeared there was a war that ended slavery but accelerated the extermination of the indigenous residents. More invaders came until they had claimed the entire continent. The political and economic system of this land was built on these crimes.

These are undeniable truths of American history that can be asserted and summed up briefly, but the devil is always in the details. Americans like to think of themselves as an exceptional people bound together by noble ideals. This belief is challenged, however, when history is taught more honestly and fully, without omitting facts or telling outright lies. Presidents are outsized characters in America’s narrative about itself. Children attend schools named after them; there are monuments dedicated to them in every state. They have their own national holiday, Presidents’ Day, which presents an opportunity for the country’s virtues to be celebrated. We are conditioned to feel a deep connection to these men hundreds of years after some of them have died.

The language used to create and protect presidential images is telling. The first several presidents are known as the Founding Fathers, a term that affirms patriarchy and white supremacy. George Washington is more than just the first president; he is the “Father of Our Country.” Regardless of our group affiliations and histories, we are taught to see these people as benevolent figures no matter what actions they took in while in office.

Most Americans are taught from childhood, for instance, that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were brave and brilliant men in any number of ways, but that both men owned human beings as slaves is rarely mentioned in telling their stories or assessing their character. Americans are not taught that the British offered freedom to the enslaved people who fought on their side in the Revolutionary War. Abraham Lincoln, widely regarded as the great liberator, initially sought to limit the spread of slavery rather than to end it, and actively considered the option of deporting or segregating black people in order to make America a whites-only society. Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy are considered to have been “good for black people,” even though they constantly feared antagonizing southern segregationists and failed their constituents.

It is particularly difficult to write about America’s history without giving in to the notion of patriotism, which includes suppressing certain narratives. Even those who think of themselves as progressives base their arguments for systemic change in terms of obedience to the cherished myths of great men. Despite claims to the contrary, Americans are highly indoctrinated to the belief in American superiority. Though the democratic progress usually amounts to a series of compromises and incremental steps, emphasizing only those facts of history that make our “great men” look good undermines the creation of the sense of inclusion and understanding necessary for the lives of all citizens to improve.

This book is an effort to shed light on the truth. George Washington didn’t have wooden teeth, as is commonly believed, but he did take teeth out of his slaves’ mouths. He may not have chopped down a cherry tree, but when Philadelphia became the capital of the United States, he deliberately rotated his slaves out of Pennsylvania in order to avoid their becoming emancipated, as the law would have required.

The very foundation of this country, the celebrated Declaration of Independence from Great Britain, was tainted by the fact that some delegates to the Second Continental Congress were keenly focused on the continuation of slavery. The case in which James Somerset, who was brought to London by his Bostonian slaveholder, was freed in 1772 threatened the future of slaveholding in the thirteen colonies. He won his freedom based on the argument that the law of England did not support slavery. Many feared that the precedent might “cheat an honest American of his slave.”

All of the men who became president were able to reach that high office in part because they swore allegiance to American ideals that were built on tenets of conquest and enslavement. These truths are self-evident: The founding of the United States continued the conquest and genocide of the continent’s indigenous population and protected the practice of slavery. The legacies of predatory capitalism and anti-black racism are a huge part of our collective story. None of this is ancient history that can be dismissed in the twenty-first century. These themes run deeply in our culture, and they should be acknowledged and understood. Aristotle said: “If liberty and equality, as thought by some, are chiefly to be found in democracy, they will be attained when all persons alike share in government to the utmost.” More than twenty-three hundred years later, we’re still not there. Americans need to recognize the malignancies that have threatened the healthier aspects of our shared history and continue to do so. If we are ever to have the opportunity to be fully realized as human beings, capable of living in peace among ourselves and the rest of the world, we need to be honest with ourselves. To the extent that our leaders embody aspects of who we are as a people, studying how each president has participated in our nation’s complicated and often shameful treatment of black people is as good a place as any to start.

Copyright © 2020 by Margaret Kimberley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.