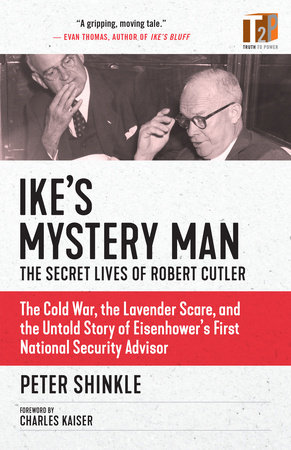

Foreword by Charles Kaiser This is a remarkable book about an extraordinary man who was Dwight Eisenhower’s “right hand” for foreign policy.

Robert Cutler, known as Bobby, was born into a prominent Boston family, the fifth of five sons whose friends had names like Cabot, Lowell, and Lodge. He attended Harvard, fought in the First World War, graduated from Harvard Law School, and served as corporation counsel for Maurice Tobin, a Democratic mayor of Boston. Then he became an army general, a senior strategist on Eisenhower’s presidential campaign, and America’s first national security advisor .

He was also a banker, a poet, a cross-dresser who loved the female roles in amateur theatrical productions, and a closeted gay man at the center of a gay White House love triangle.

Ike’s Mystery Man is the perfect title for Peter Shinkle’s fine biography. One of the big headlines here is about Cutler’s shepherding of a disastrous 1953 executive order that destroyed the lives of thousands of federal employees, just because they were gay.

Shinkle writes that Cutler, like nearly all gay men of his time, “struggled profoundly to find, recognize, and accept his sexual and romantic orientation.” And like far too many of his contemporaries, he was perfectly willing to promote discrimination against other homosexuals, if it would help deflect suspicion from himself.

The author of this book is the great-nephew of his subject. He first learned of Cutler’s sexuality in a casual conversation with his aunt long after Cutler’s death. Shinkle has done a superb job of untangling the crosscurrents of postwar Washington, when the Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, his evil henchman Roy Cohn, and their ally Vice President Richard Nixon made themselves notorious by persecuting former Communists and current homosexuals, whom they portrayed as mortal threats to the government. (Twenty years later, Cohn became the tutor in the dark arts of bluster and bullying for another disastrous Washington disrupter: Donald Trump.) Ironically, Eisenhower’s executive order banning gay people from the federal government and all its contractors was part of his effort to extinguish McCarthy’s work.

Shinkle identifies two books published in 1948 as landmark events for gay Americans. Gore Vidal’s bestselling novel,

The City and the Pillar, ripped away the secrecy enveloping the fancy gay worlds in Hollywood and Manhattan, just as

Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, by Alfred Kinsey, shocked America by reporting that 37 percent of all males had had at least one homosexual experience in their adult lives. Together, Shinkle observes, these books spurred “a revolution in public perceptions.” The author also has an intriguing theory: “By raising homosexuality in the public consciousness, the Kinsey and Vidal books may ironically have contributed to a period of heightened discrimination” in the 1950s, after the relatively permissive years of the Second World War.

“A strange climate of paranoia and dishonesty permeated Washington,” Shinkle writes, “where vicious hunts for homosexuals were led by men themselves suspected of being gay [such as McCarthy and Cohn], where people laughed as [Joseph] Welch and McCarthy sparred maliciously over the words

pixie and

fairy . . . and where senators practiced the art of gay blackmail against political foes . . .

“Homosexuality was simultaneously everywhere but nowhere, suspected but not proved, concealed but then revealed, loathed and labeled a security risk — but then giggled about. Amid it all, from . . . deep inside the NSC and the White House, Bobby and Skip were doing their best to serve President Eisenhower and fight Communism.”

Skip was Tilghman “Skip” Koons, a gorgeous twenty-seven-year-old Russian speaker whom Cutler recruited for the National Security Council staff. How Koons’s homosexuality failed to prevent his employment is a mystery: Shinkle speculates that because of his experience with the CIA and in naval intelligence, he may not have received a formal FBI background check. He was recommended to Cutler by an ex-lover, Steve Benedict, whom Cutler knew from the Eisenhower campaign.

Incredibly, at the height of the gay witch hunt in 1954, Benedict also joined the White House as its security officer — and the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, invited him to a cocktail party to celebrate his appointment.

Cutler left his White House post before the 1956 election, possibly because of fears that his orientation might become public. But he returned for Eisenhower’s second term.

He was completely besotted with Koons, to whom he wrote wild love letters quoted in these pages: “Out of all the concerns in my world this interest in you and yours predominates. As if some electric current, invisible but sure, pulsed across the sea to communicate between us. I hope this can always be so . . .”

Cutler was a fierce workaholic who confided to Koons that he was taking an amphetamine, Dexedrine, to wake up and a barbiturate, Seconal, to go to sleep. Koons was less than half his age. Eventually, the older man presented the object of his affection with a 163,000-word journal about their relationship, which may or may not have gone beyond hand-holding. Benedict inherited that diary and six hundred letters between Cutler and Koons. He gave it all to Shinkle, a research bonanza that made much of this book possible.

All three men lived on a razor’s edge. In 1957, a White House correspondence clerk named George Dame was arrested in the men’s bathroom in the library of George Washington University by a member of the vice squad. Dame named two other gay White House staffers; one of them told the FBI that Cutler was gay. Hoover took personal charge of the investigation. Once again, mysteriously, he took no action, possibly because it would have damaged his relationship with the president.

Hoover himself had a “spousal” relationship with his deputy Clyde Tolson that, according to his biographer Richard Powers, was “so close, so enduring, and so affectionate that it took the place of marriage for both bachelors.” But since Hoover’s was the only Washington house that was surely never bugged by the FBI, what actually happened inside his bedroom is lost to history. Truman Capote memorably described the FBI director as a “killer fruit . . . a certain kind of queer who has Freon refrigerating his bloodstream.”

Cutler was a wildly emotional gay man. After his dying mother gave him her mother’s wedding ring, he had it engraved with their initials and his own — and wore it for the rest of his life. When he was sixty-seven, he boasted to his diary that he was “emotionally immature . . . And I thank God for it. For the alive freshness of early and penetrating feelings, rushing through me like a wild west wind.”

There is much more to this terrific book than the private life of a tortured gay man. It covers all the major events Cutler was involved with at the White House, including American-organized coups in Guatemala and Iran, the fight over a security clearance for J. Robert Oppenheimer, American nuclear policy in the 1950s, and the earthquake caused by the launch of Sputnik, the first human-made satellite, by the Soviet Union.

This book also provides a revealing portrait of the power of the military-industrial complex, which Eisenhower famously warned against in his farewell address. The bank Cutler worked for in Boston had close ties to the United Fruit Company, and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had been managing partner of the New York law firm that represented Standard Oil of New Jersey. Both corporations received considerable protection when the Justice Department tried to pursue them for anti-trust violations.

This is an important and constantly surprising work by a former investigative reporter. Shinkle’s sophistication, the multiple secrets he uncovered, and the breadth of his narrative make it one of the most rewarding books of popular history I have ever read.

— Charles Kaiser

Copyright © 2021 by Steerforth Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.