Preface

Poll after poll demonstrates that year after year Americans’ basic historical knowledge reaches newly obscene lows. This trend takes on increasing urgency when we observe political leaders and senior policy makers direct foreign and domestic affairs in the apparent absence of knowledge of relevant historical context. Frankly, it is embarrassing to watch, and often tragic in its human consequences.

I was first struck by the severity of this problem when I returned to my alma mater, the United States Military Academy — West Point — to teach freshman (“plebe”) American History 101. I was straight out of graduate school, my sense of the decisive importance of the subject heightened by my tours in Iraq and Afghan where I fought in wars begun and waged seemingly without the faintest sense of the region’s history. That the cadets would likely, almost inevitably, form the increasingly militarized vanguard of future US foreign policy only added urgency.

Most cadets entered West Point having been taught — and thus understanding — a rather flimsy brand of US history. These otherwise gifted students’ understanding of the American past lacked substance or depth, and pivoted on patriotic platitudes. Such young men and women hardly knew the history of the country they had volunteered to kill and die for. That, I thought to myself, is how military fiascoes are made.

Throughout my teaching tenure I set myself the task of bridging — in some modest way — the gap between what scholars know and what students learn. That process and its challenges motivated me to write this book: an enthusiastic attempt to bridge the perhaps unbridgeable — academic and public history. No doubt the project will be found wanting, but there’s inherent value in the quest, in the very struggle. The skeletal geneses of the chapters that follow were the thirty-eight lesson plans I crafted to impart the broad contours of US history to future leaders of an army at war.

That the often censorious — some will say downright un-American — analyses herein were introduced to presumably patriotic and conservative West Point cadets may seem shocking. That many other history instructors on the faculty presented not altogether dissimilar concepts may be more surprising still. Nonetheless, as Martin Luther King Jr. often warned: We should not confuse dissent with disloyalty. In today’s politically and culturally tribal times, unfortunately, this seems the reflexive response to any manner of disagreement.

I make no apologies for having presented combat-bound cadets with undeniable dark facts and some critical conclusions common among esteemed scholars. Exposure to the historical myths and flaws — in addition to the well-worn triumphs — of the country they might very well die for seemed appropriate. Anything less would have felt obscene.

#

I write this preface amid both a deadly pandemic and widespread demonstrations in communities large and small inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement that have shaken many Americans’ perceptions of the nation’s political and economic systems to the core. Whether these historically unprecedented events will translate into structural or lasting change is unclear, but there’s no better time to translate the version of American History 101 that I taught at West Point to a public audience and to pose the salient question: What, exactly, is exceptional about the United States?

America is exceptional — not always in ways that should engender patriotic pride, but rather often in ways that should cause us to reflect, take stock, and strive to do better. Plenty of other countries, for instance, sport equally (if not more) free and democratic societies; dozens are healthier and provide superior medical care; some are even more affluent.

Hardly any, however — particularly in the wealthier “developed” world — have such vast wealth gaps, disparate health services and outcomes, or traditionally weak left-labor parties. Essentially none imprison quite so many of their citizens, militarily garrison the globe, or fight even a fraction as many simultaneous far-flung wars. Even if we were to set aside any associated value judgments, it bears asking why — historically speaking — this is the case.

Why does the United States have income inequality rates equivalent to those of its Gilded Age more than a century earlier?

Why didn’t its citizens insist upon, or achieve, universal public health care before — and especially after — the Second World War, when most of its Western allies and even adversaries did?

Why was there, at least in comparative terms, never a viable socialist or serious labor party alternative in mainstream American politics?

Why has an unprecedented class- and especially race-based mass incarceration regime developed in the nation that most loudly proclaims its dedication to freedom?

And why is it the United States wages undeclared warfare across the planet’s entirety?

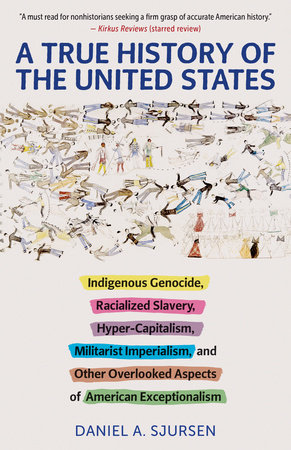

Many of the answers actually lie in the past, in the historical development of US politics and society. These aspects of the darkly exceptionalist present can only be understood through — and partly explained by — a better understanding of four ghastly themes underpinning American history but largely glossed over in standard, introductory survey classes: indigenous genocide, racialized slavery, hyper-capitalism, and militarist imperialism.

Many people loudly claim to hate history, at least as a subject in their schooling. Given the uneven quality of its teachers and consequent presentation, that’s quite understandable. Still, distaste for the history class hardly tempers the inordinate value nearly all Americans place on the concept of history, at least as they choose to understand it. Most people understand themselves, their family, their community, and their nation through the prism of history. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are, the public policy we craft, and even what we imagine possible.

Copyright © 2021 by Daniel A. Sjursen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.