I

SIX DEGREES

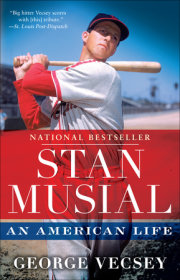

In 1958, the St. Louis Cardinals made a barnstorming trip to Japan on the golden anniversary of the first visit by two major league squads. Among the Cardinals' entourage was Stan Musial, about to turn thirty-eight, old by baseball standards, but still exhibiting his characteristic smile and convoluted batting stance.

In the city of Tokyo was a seventeen-year-old prospect named Sadaharu Oh, the son of a Chinese noodle shop operator and a Japanese mother. Oh was already Japan's best-known high school player. His batting coach, Tetsuharu Kawakami, strongly suggested that Oh adapt Musial's coiled stance. “Hitting is with your hip, not with your hand,” said Kawakami, who had won five batting titles in Japan.

With the obstinacy of a seventeen-year-old, Oh declined. Several years later, on the brink of failure that was partially self-induced through his excesses and hardheadedness, Oh would submit to his guru. With the hope of salvaging his career, Oh would accept an even more idiosyncratic posture—“the flamingo stance,” the Japanese would call it. He would raise his front leg, the right one, forcing his weight and power to his back foot. The new stance had its roots in the twisted Musial position.

That earnest trip in 1958 was regarded as something of a failure by Musial, who hit only two home runs for the adoring Japanese fans. “I was tired, worn out after the regular season,” Musial would recall thirty years later. “I'm sorry they couldn't have seen me earlier.” Yet the trip by the Cardinals would help produce the greatest home run hitter in the history of baseball, as Sadaharu Oh would eventually hit 868 home runs.

Years later, Musial and Oh would meet, shake hands, and bow to each other, left-handed sluggers from opposite shores, comrades in unorthodoxy.

This is the beauty of baseball. Everything is connected, either by statistic or anecdote or theory or history or the infallible memory of a fan who was there, who saw it, who can look it up. It is possible to sit in the ballpark (not the stadium, not the arena, but the ballpark, a homey title claimed only by baseball) and, during the process of one game, watch several overlapping games, overlapping generations and histories, all at once. The grandson, if he is not looking around for the hot dog vendor, may see Ichiro Suzuki slap a double into the corner. The grandfather may be thinking of how Stan Musial used to smack doubles just like that.

—

The American playwright John Guare is known for his enduring play Six Degrees of Separation, based on a theory that there are no more than six layers between any two people on the planet. Guare was not talking about baseball, but he could have been. The so-called American game has existed in a straight and highly detectable line since the 1840s—and backward into earlier times on other continents.

The game is perpetuated in raucous living museums, many of them in the center of cities, on a continent just beginning to have some history to it. Some cities have been playing other cities for a long time now, by American standards. These old places contain triumphs and resentments, nowhere near the rivalries of the old city-states of Europe, but the beginning of history, at the very least.

The hearts of the fans contain memories of something horrible that happened in 1908, or 1940, or maybe even last week. No other American sport has so many ancient joys and sorrows. It sounds overbearingly cutesy when sportswriters in Boston refer to the Red Sox as Ye Olde Towne Team, yet in that marvelous October of 2004 the Sox labored under a cloud of communal frustration dating back to 1918 when Babe Ruth pitched the Sox to a championship, and was soon sold to the New York Yankees. When the Sox went on their memorable eight-game romp in 2004, you could hear the brass band of a century earlier: a local rock group had resurrected “Tessie,” the anthem of the very first World Series of 1903. Base-ball's history echoed in vibrant Fenway Park as well as the crooked streets and anarchic traffic of Boston.

Baseball fans know these links, discuss them in dens and bars and playgrounds and even at contemporary ballparks—that is, when they can be heard above the god-awful din of the modern sound system. These memories are much more than trivia or statistics; they are a way of keeping history alive.

The sport has a timeless feel to it, as if it has always been here. That is because each game is unfettered by the tyranny of a stopwatch, as anybody will attest who has ever held car keys in hand, poised in an exit portal, only to witness a nine-inning game suddenly lurch into extra innings. I am thinking here of a marathon I once covered as a young reporter in 1962, the first year of Casey Stengel's Amazing Mets, who very quickly established themselves as the Worst Team in the History of Baseball, capital letters and all. On a chilly spring night, the Mets played the equally wretched Chicago Cubs in extra innings. The game seemed interminable— refreshment stands were closed down, children were fast asleep on their parents' laps, and fans were beginning to dread getting up for work in the morning. As I sat in the stands to savor the mood of this horrendous new team so gloriously born in New York, I heard one fan say to another, “I hate to go—but I hate to stay.” Those words seemed to sum up the morbid compulsion that keeps fans in their seats, quite unable to leave this silly game.

The absence of a clock is matched by the perfection of the calendar. The season begins in the hopefulness of early spring and it flourishes in the heat of the summer and then it breaks hearts in the nippy evenings of late October.

Plus, they play it every day. No other sport in the world can match baseball for constant adventures, new results. All around the world, at every moment, there are compelling sports events, many of them presented on multiple television channels—soccer goals rocketing into the net in Rio, basketballs dunked in Shanghai, nifty putts in Madrid, dazzling backhands in Melbourne, gaudy touchdowns in Dallas, vehicles whizzing across finish lines in Monte Carlo or Daytona. But only baseball summons the same cast of characters to return, a few hours after the end of the previous game.

“Let's play two,” chirped Ernie Banks of the Cubs, who had often played two or even three games a day in the Negro Leagues and became an icon in the major leagues for his celebration of the daily ritual.

No other sport has this endurance. American football players must go back into their bunkers to receive six days of drills before their bodies heal enough to play again. Likewise, basketball, soccer, and hockey players cannot play every day. Yet barring injuries, baseball regulars are expected to start in 140 or 150 games out of a total of 162, with starting pitchers expected to throw once every five days.

The result of this regularity is a delightful soap opera that airs virtually seven days a week. The player who muffed a fly ball last night or stole a base or made an incredible catch must go back out there today, in front of fans who reward him or revile him for events only a few hours old.

These daily games seep into the consciousness of citizens who insist they have stopped paying attention to baseball. People say they became disillusioned at their favorite team's defection to another town or the serial labor shutdowns of the past generation, and they claim they would rather watch pro football or stock cars going around in circles, or whatever. They declare they are turned off by high salaries as well as the steroid generation that saw bulked-up sluggers whacking home runs at an unprecedented rate, but the reality is that baseball has survived gambling plots, outlaw leagues, racial segregation, depressions, world wars, the early death of a stunning number of its heroes, financial failures of teams, inept ownerships, the bad taste of its sponsors and networks, blundering commissioners, inroads by other sports. It endures.

Copyright © 2008 by George Vecsey. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.