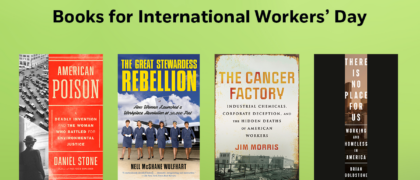

1

Alice Hamilton in 1915.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1919

For as long as America had existed, one of the country's top centers of knowledge and science circled a large patch of grass two miles west of Boston. America's first university had begun here in 1636 as a school named for a Puritan clergyman who donated half of his life savings and four hundred books to start a college in the new colony in the Massachusetts Bay.

In the three centuries since its founding, Harvard University had expanded in size and space and grown John Harvard's initial endowment to almost $10 million. But the patch of grass remained, now with walking paths and black iron benches, all surrounded by large buildings where the finest professors gave the finest lectures to the finest students, all of them men.

Alice Hamilton sat on a bench on the morning of March 15, 1919, amid snow flurries, looking at the burned crater of Dane Hall, a building in the center of campus that had been destroyed in a spectacular fire the year prior. She had just come from a meeting with the dean of Harvard's medical school, David Edsall, who, outside of his dean capacity, happened to be an expert in the effects of extreme heat in enclosed spaces.

Hamilton's meeting with Edsall was the final step in a long-running conversation that took place by typewritten letters that shuttled between Cambridge and Chicago, where Hamilton lived. The discussion in these letters was timid and noncommittal, at least at first, because it was about something no dean at Harvard had ever thought about, much less acted upon. Edsall wanted to recruit Hamilton to join the faculty of Harvard. If Edsall was successful, Hamilton would be the first woman ever considered for the faculty ranks.

Hamilton sat quietly watching male students walk in and out of the buildings. She was short, five foot four, with light brown hair parted down the middle. She wore a beige turtleneck with a brown blazer, an outfit she confided to a friend that she favored in professional settings because it looked sharp but bland, and not overly feminine. The snow was melting and signs of life had returned to the university quad. In front of her, two students tossed a ball, their breaths forming clouds of vapor. Other students sat on the steps of Sever Hall with their heads buried in books.

Hamilton's path to that bench had been uneven, even rocky at times. She was born in 1869 into a wealthy family, one of the richest in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and had grown up in an estate covering three city blocks that was owned by her grandfather, who had made a fortune in land speculation and railroad promotion on Indian lands. By the time Hamilton was four, her father, Montgomery Hamilton, pushed Alice and her three sisters to direct their own education by reading books. Montgomery believed that all education should be rooted in learning languages-Latin, French, and German-which would open a wider array of books for his girls to learn everything else themselves.

When Hamilton turned seventeen, she went away to boarding school at Miss Porter's School in Farmington, Connecticut. Miss Porter's provided the hunger for more formal learning that Hamilton needed. The curriculum was created by Sarah Porter in 1843 to teach young girls to be good Christians first and, secondly, to be good wives and mothers "whose influence would shine like a saving light in a domestic world." Porter was morally opposed to excess, corruption, and selfishness and worked to make her school an epicenter of reform to move girls forward on the educational and social track. She had no interest in frivolous activities or distractions. "There may be dancing in the backroom of the wing," the school's handbook read in the 1850s. "But Miss Porter wishes that there should be no waltzing."

For Hamilton, the straitlaced education worked. She graduated with a well-formed goal of becoming a doctor who could help people, which launched her almost immediately into medical school in Michigan. A year later, at twenty-four, she had a medical degreeand, not long after, a job studying pathology at Northwestern University in Chicago. To be young and unattached was a great pleasure for Hamilton. Her days were full of research and correspondence, and her evenings were entirely hers to roam Chicago and attend lectures, plays, and musical performances-a cosmopolitan life in the Gilded Age for a woman who had no interest in bothersome distractions like men, children, or making money. As the decades passed, she developed an expertise and, with it, a reputation.

The original spark that brought Hamilton to Harvard was a conversation between the owners of Boston's three biggest department stores: Filene's, Gilchrist's, and Jordan Marsh. Two years earlier, in 1917, one of the store owners began to notice that the turnover of his workers for health-related reasons was so high that it was beginning to be a drag on his business.He mentioned this to the other owners, who admitted to having the same problem. The cause of so much sudden illness was a costly mystery.

Together, they agreed a survey should be done about the general health of department store workers and the reasons for their illnesses-not necessarily for the sake of the workers, but for the owners to have more reliable employees and thus keep up their receipts. They proposed the idea to the Massachusetts Retail Trade Board, and a year later the board came up with $50,000 for a five-year study of retail workers.

Harvard was the obvious venue for such a study. Its medical school was the most authoritative in the country, and it happened to be an hour from downtown Boston by foot and twenty minutes by automobile. Edsall was delighted when a member of the Retail Trade Board offered him the money to do the study. All he needed was somebody to design and run the investigation. A search was done of professors at other universities that could be brought to Harvard. But the field of industrial medicine, as it was clumsily called, was less than a decade old, with few seasoned experts.

Edsall remembered an article he had read years earlier in the Boston Globe about how Dr. Alice Hamilton, a Chicago physician, conducted a similar occupational investigation in 1911 commissioned by the governor of Illinois that looked at the conditions of workers in lead factories in Chicago and found detailed and actionable ways to improve worker health. In Edsall's mind, this made Hamilton the leading candidate for the job, and also the only one.

When he tried to get in touch with her, Edsall was surprised to learn that Hamilton had a richer résumé than just the Illinois survey. In her thirties, Alice Hamilton had single-handedly created and become the de facto head of an entirely new field of medicine rooted in exactly this kind of research. The dangerous trades, she called them-the factories and smelters that manufactured materials, fuels, and consumer products, and the workers who operated these facilities.

In a time of booming production and thousands of buzzing factories across America, Hamilton was one of the first people to wonder about the health of the workers. And when she did, she found countless instances of men who toiled with scarcely any protections at all. No uniforms, no gloves, and-for those who worked with especially gruesome chemicals like mercury and lead-no respirator masks. "Dangerous" was a gentle word for these jobs. Often they were deadly.

Hamilton was sympathetic toward the men who held these jobs. They were usually European immigrants, almost all of them living on pennies. Most spoke broken English at best, which left them marginalized. Holding no political or economic power, they had little choice but to accept any work they could find, no matter how paltry or perilous.

What was more, Hamilton lived in Chicago, a city newly infamous for exactly this kind of worker peril. Most worker drudgery was kept hidden from view to protect rich people from confronting such ghastly tales. But that changed in 1906 when Chicago's slaughter yards and packinghouses made international news. A socialist writer named Upton Sinclair had embedded himself for two months in Chicago's Packingtown, as it was called, where he observed unspeakable squalor, including workers living twelve to a room in fetid boardinghouses and packing floors so dirty that even a scrape of one's knuckles could cause an infection that could kill a man in days. Sinclair's work was eventually published as a novel he titled The Jungle that, despite containing composite characters and some fictional details, included stomach-churning scenes that shocked the Victorian sensibilities of the upper class. In one of the worst, Sinclair wrote of men who accidentally fell into hog vats and were boiled alive, then were fished out, ground up, and sent out to the world as Durham's Pure Leaf Lard.

In the early 1900s, the law protected people making money, not the workers with hand sores, broken bones, and breathing difficulties. Even children were swept into the gears of American industry far more than in European countries that had long-standing child labor laws. In 1900, 2 million U.S. children still worked in mills, mines, fields, and factories. Two attempts by Congress to protect children from exploitation were overturned by the Supreme Court until, in 1938, a law called the Fair Labor Standards Act finally stuck. Immigrants, however, had no such heartstring appeal. The lines of desperate workers that formed outside factories were all but proof to business owners that nothing needed to change.

The worst workplace dangers were usually the hardest ones to see. Any man knew he could accidentally cut his finger off while using a sharp knife to debone a cow. Or he could eventually end up with a burn if he shoveled bricks into a furnace. But it was harder to link the effects of breathing mercury vapors to future lung disease, or the lack of coverall uniforms to crippling body pains that would land a man in bed and eventually the grave.

Hamilton's talent was finding the connections. Her usual process was to interview sick men in their homes and at their bedsides-or, worse, to interview their widows about their husbands' last days-and then compare the details of their afflictions to the symptoms of other men. With enough data, she could find patterns. "Shoe-leather epidemiology," someone called it.

She loved this work. According to one biographer, she enjoyed the one-to-one relationship between cause and effect so rare in medicine. Her work was both scientific and personal, and it fit squarely with her childhood goal that she could somehow, in some way, "make the world better."

The work also suited her. The one factor that made her especially good was knowing how to use her gender to her benefit. A man showing up for a surprise inspection at a factory would get turned away for fear that he was an agent for the government or a competing company. But a woman posed no threat at all, especially a five-foot-four soft-spoken one who was not angry or rude but relentlessly polite and curious. What harm could she bring? Being underestimated had its benefits.

In the weeks before their meeting at Harvard, Edsall appealed to Hamilton’s sympathy for the toiling American worker. “I am writing . . . to ask you whether you would consider taking charge of this work,” Edsall wrote to Hamilton two days after Christmas in 1918. “It is apparent, I think, that there is a very large opportunity for public service in a field that has been very inadequately studied.”

He also toyed with Hamilton's sense of prestige, making an opportunity no woman had ever been given. "It is the first time that the proposition has ever come up to have a woman appointed to any position professorial or other in the University." He said he thought it would be a "large step forward in the proper attitude toward women," particularly at a time when most colleges didn't admit women even as students, let alone faculty. Schools that did subjected them to such crippling discrimination that, less than fifty years prior, several philanthropists endowed a series of women-only colleges in the Northeast where they could study without harassment.

Flattery could boost her ego, but Hamilton was not in need of a job. In fact, what she needed was less work. For the past five years Hamilton had lived in feverish motion between Chicago, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Several months before, she had agreed to oversee a survey for the Department of Labor on stonecutters who were coming down with high rates of tuberculosis due to a new mechanical cutting device that cut stone ten times faster but also produced ten times as much dust. A woman who had even basic competence in medical matters surprised many men, and when they learned she was untethered to a husband or children, professional opportunities often followed-sometimes too many of them.

Plus she already had money, enough to suit her, and all of it hers. She bought a winter home with her sisters beside the Connecticut River near New Haven and would travel to Michigan in the summer. She accepted an invitation in 1915 to the International Congress of Women in The Hague in the Netherlands and was often asked to do work for the National Research Council and the Public Health Service. The rest of the time, she simply went wherever anyone invited her to research, study, or speak.

When the letters started appearing from Harvard, Hamilton at first ignored them. She thought it was a hoax or a condescending appeal for a woman to make the men feel virtuous. When they kept coming, she wrote to her sister Edith, to ask how she should respond. Many other women might have jumped at the chance to join America's most exclusive boys' club. But Hamilton and her sister were not ordinary women.

Besides, Hamilton didn't want to do the department store study, which sounded boring. She had plenty of work and her schedule was full. And she didn't want to move to Boston. It was too far, it was too cold, and she had no friends there.

Finally, in January of 1919, she responded to Edsall, saying no thanks. She could not commit to a full-time study, and she was not the right person to conduct hundreds of interviews with department store workers, who were mostly women inclined to small talk and chitchat. She was accustomed to interviewing men, ones who worked in factories, mines, and smelters. And besides, a survey of department store workers-not exactly the most marginalized of people-would be funded by the industry, which all but guaranteed corporate handholding. She had been through this before. An industry only wants to uncover problems it can easily solve, not ones that make it look bad.

How about half-time? Edsall responded. And forget the department store work, he said. Hamilton could come to Harvard simply to teach. She could instruct a class in industrial poisonings, he said, or, frankly, whatever she wanted to do. September to February. Free housing. And $2,000 a year, a sum $200 more than the average Harvard salary.

Copyright © 2025 by Daniel Stone. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.