MaryamI am fourteen the year I read Surah Maryam. It’s not like I haven’t read this chapter of the Quran before, I have—I’ve read the entire Quran multiple times, all 114 chapters from start to finish. But I’ve only read it in Arabic, a language that I don’t speak, that I can vocalize but not understand, that I’ve been taught for the purpose of reading the Quran. So I’ve read Surah Maryam before: sounded out the letters, rattled off words I don’t know the meaning of, translated patterns of print into movements of tongue and lips. Read as an act of worship, an act of learning, an act of obedience to my father, under whose supervision I speed-read two pages of Quran aloud every evening. I’ve heard the surah read, too—recited on the verge of song during Taraweeh prayer in Ramadan; on the Quran tapes we listen to in the car during traffic jams; on the Islamic radio station that blares in the background while my mother cooks. This surah is beautiful, and one that I’m intimately familiar with. The cadence of its internal rhyme, the five elongated letters that comprise the first verse, the short, hard consonants repeated in intervals. But although I’ve read Surah Maryam before, my appreciation for it has been limited to the ritual and the aesthetic. I’ve never read read it.

I am fourteen the year we read Surah Maryam in Quran class. We, as in the twenty-odd students in my grade, in the girls’ section of the Islamic school that I attend in this rich Arab country that my family has moved to. It’s not a fancy international school, but my classmates and I are from all over the world—Bangladesh, Nigeria, Egypt, Germany—and our parents are always telling us to be grateful for our opportunities. Mine are always reminding me why we left the country I was born in a decade ago—a country where we lived next door to my grandmother and a few streets down from my cousins, where I remember being surrounded by love—to this country where we don’t know anyone and don’t know the language and my mother can’t drive. My parents are always listing reasons we’ve stayed: better jobs, more stability, a Muslim upbringing. Which includes an Islamic education in school.

Twice a week, my classmates and I have Quran class. We line up in the windowless hallway outside the room where we have most of our other lessons—a room we’ve decorated and claimed desks in and settled into. From there, we begrudgingly make our way to a drab room in the annex called the “language lab.” The name is deceptive; it’s just a regular classroom outfitted with headphones and tape players, recently appropriated from the boys’ section in an attempt at a more equal distribution of the school’s resources. But gross boy smells—sweat and farts and cheap deodorant—still linger in the windowless room, and it’s a five-minute walk away on the other side of the school’s campus. Understandably, the rate of attrition is high for these trips to Quran class. Girls duck out to the bathroom along the way and fail to rejoin the procession (“Miss, I really have to change my pad, but I’ll be right back, wallah”), or feign ignorance of where class is being held (“Miss, someone told us the language lab is closed this week so we waited in our classroom the entire time”), or pretend to have gotten lost (“Miss, I really thought I had to take a right at the stairs and by the time I figured it out, it didn’t make sense to disturb the lesson”). It is unbelievably easy to skip Quran class.

I, on the other hand, never skip Quran class. I go to every single one without fail, not because of religious devoutness, but because that’s the kind of ninth grader I am. Too scared to cut class and a terrible liar. An overachiever, hell-bent on getting good grades and ranking first in my class. A nerd, hungry to learn about anything and everything; an avid reader, fascinated by the storytelling aspect of Quran class and eager to know what happens next; a clown, unwilling to give up having an audience for the jokes and convoluted questions and inappropriate remarks that I offer in class, preferring the laughs and groans and eye rolls of my classmates to being with myself, to the thoughts that pulse through my solitude.

But also, there’s this: I’m bored. I’m thoroughly bored by school. I’ve figured out that each class contains only about ten minutes of actual learning that I need to pay attention to at the start of the period, and then I can tune out. I’ve figured out that my teachers are puzzles that can be cracked with a little effort at the beginning of the semester: which teachers reward acting like you’re trying hard, which ones have soft spots for quick-witted students, which ones just want everyone to be quiet in class. I’ve figured this out: once I listen for a bit in class and grasp the new material and win over the teacher, I can spend the rest of the time doing whatever I want. Sometimes this means decorating my pencil case with correction fluid; other times it means reading contraband novels under my desk. Sometimes it means disrupting the class: coming up with pointed questions of existential importance that I just need to ask the teacher now. But mostly, it means whispering with—and distracting—whoever ends up sitting next to me.

This Quran class is no different. We are slogging through Surah Maryam painfully slowly, about ten verses at a time. The only part of class I enjoy is the beginning. We start by listening to the recitation of the verses in Arabic. One of the girls in my class is a Quran aficionado and brings in tapes of reciters with lush, melodious voices. I put on my headphones, close my eyes, and for a few minutes let the sounds wash over me. I lose myself to the tune set by the rhyme, I let myself be moved. This part always comes to an end too soon. The teacher stops the tape and takes over, reading the verses one by one in a stoic monotone, each word clear and well enunciated. And we follow, mimicking her tone and reciting lazily, most of us just mumbling through and letting the Arab girls who know what they’re doing take up the bulk of the aural space.

The next part of class is the translation. We read the English meaning of the Arabic words we’ve just recited, with everyone taking turns reading one verse aloud from our government-issued Qurans. I deliberately sit near the back of the class so we’ll be done reading before my turn comes, so I can skim through the translation of the verses we’ve read and then blissfully tune out the rest of the lesson. Today I’m composing a note on my calculator to my best friend, with whom I’ve been trying to come up with a code using numbers and symbols and the smattering of letters on the keyboards of our scientific calculators—then someone in the first row reads the translation of this verse aloud:

And the pains of childbirth [of Isa] drove her [Maryam] to the trunk of a palm tree. She said, “Oh, I wish I had died before this and was in oblivion, forgotten.” (19:23)

I stop writing my note, stop looking at my watch, stop trying to decide what I’ll eat for lunch, stop breathing for a second. Because this verse is saying that Maryam wants to die. Maryam, of the eponymous surah we’re reading, wants to die. Maryam—who has a whole chapter devoted to her in the Quran, this woman beloved to God, the mother of a prophet, held up as an example to mankind—is saying she wants to die. In this difficult moment of childbirth, of birthing the prophet Isa, who will go on to birth the entire religion of Christianity, this Maryam is talking to God, complaining to God, screaming in pain to God that she wants to be in oblivion, forgotten. That she wants to die.

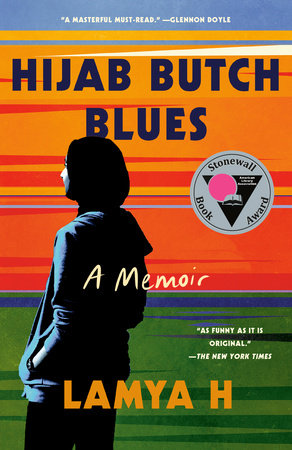

Copyright © 2023 by Lamya H. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.