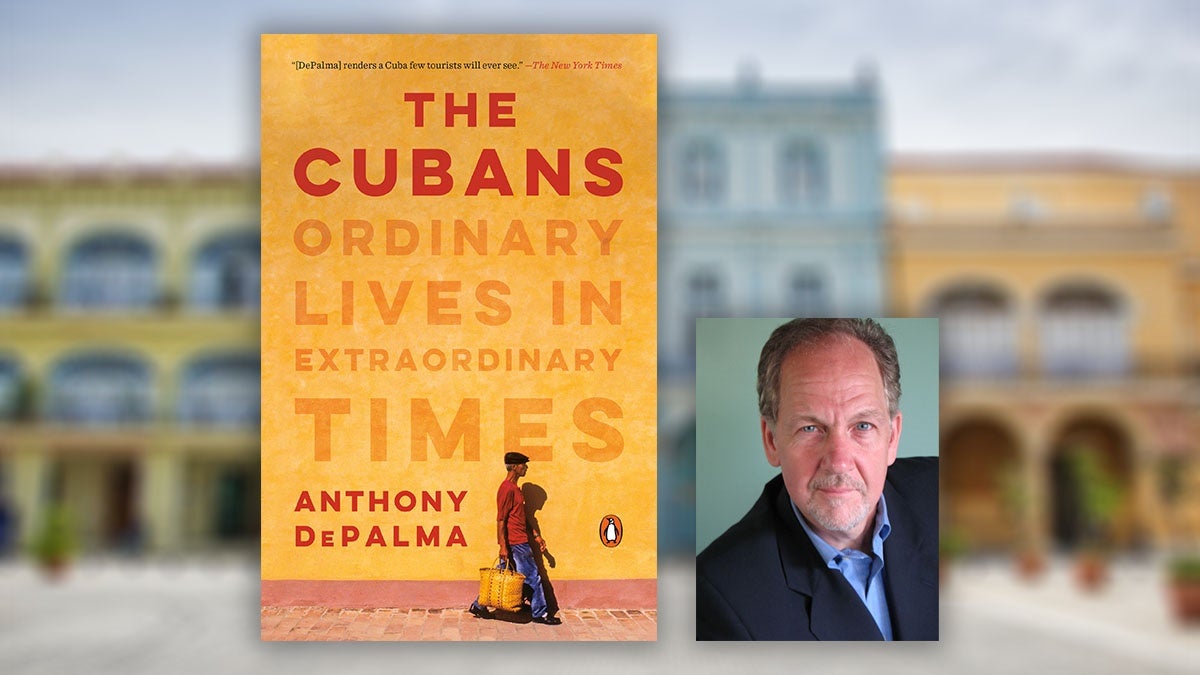

CHAPTER 1

Tacajó, Oriente Province

1940

Anyone who lived in the Cuban jungle in the 1940s knew that with the humidity and infernal heat seeping under, around and into everything, ants would get into the bread no matter what you did. Tie it up in a bag and hang it from a nail and before long there’d be a conga line of ants climbing straight up the wall like they had formal invitations to dinner. As a poor teenage girl in the sugar mill town of Tacajó, deep in Cuba’s wild Eastern end, Zenaida Ewen went only as far as the sixth grade in the mill town’s school, where classes were taught in English and a little Spanish for the children of the Jamaicans who worked there. But she had watched her mother put bread on the stove and she knew that keeping it close to but not in the flames drove drive out the ants before dinner was served.

Jamaicans had lived in Tacajó since the mill began grinding sugar cane in 1917. They came during the boom years following the Spanish-American War when foreign money—mostly American dollars--poured into the island. Cuba hadn’t come out of its war as the fully independent nation that many had fought for, but for those who did business with the North Americans, times were good, especially in Oriente province. The fertile mixture of sun, soil and rain made land there ideal for growing things, including the dense fields of sugar cane that for a time made Cuba the world’s biggest supplier, and cemented sugar so firmly into the economy of the country that people grew fond of saying “Without sugar, there is no country.”

Turning oceans of green stalks into the white sugar crystals that sweeten coffee and cake around the world has been back breaking work since the first cane fields were harvested centuries ago. By the early 19th Century, African slaves were dragged in to do the work but Spain, Cuba’s colonial master for 500 years, never allowed as many slaves into Cuba as were brought to other Caribbean islands. The slave trade was abolished in Cuba in 1820 but it wasn’t until 1879 that the institution of slavery ended. British historian Hugh Thomas surmised that the Cuban upper class almost certainly would have pushed harder for full independence from Spain “had it not been for anxiety about their slaves, and the specter of Haiti.” After the USS Maine was sunk in Havana harbor in 1898, and the U.S. jumped into Cuba’s long-running independence war, Spain was forced to give up its prized colony. Cuba became a republic but one saddled with ambiguous democracy, incompetent leadership and a legacy of racial prejudices that has never been fully erased.

With the influx of foreign investment in the early 20th century, the Tacajó Sugar Corporation, headquartered in New York, grew rapidly and prospered. The United Fruit Company, with operations nearby, also expanded aggressively, buying from local growers like Angél Castro, a Spanish soldier who settled in Cuba after the war ended and who was amassing a fortune on Manacas, his 20,000-acre plantation not far from Tacajó. Such a shortage of labor developed that the Cuban government in 1922 authorized Tacajó Sugar and United Fruit to import thousands of contract workers to help with the harvest, expecting to send them back home after the season ended. Most were Haitians or Jamaicans. Many never left.

Zenaida’s mother, Sarah Ann Ewen, was 29 when she received her Jamaican passport in 1922 and made the trip from Kingston to Cuba, drawn by the image of a Cuba filled with opportunity. She landed in Santiago and then made her way overland to Tacajó where she had heard about the good life that Jamaicans had discovered there. The lush valley around the sugar mill reminded her of home but it was no paradise, especially for a single mother with little education and no skills. Most of the streets were unpaved, sanitation was crude, and the cycle of work at the sugar mill meant periods of intense labor followed by months of dead time. That was if you had a job. Sarah needed to find one, and fast. Women didn’t work in the mills then, but they cooked and cleaned, which Sarah could do. She started washing clothes for the single men who lived in broken-down dorms. Later the mill’s Cuban doctor took her in as a domestic servant to help his wife run their big house near the main entrance to the mill. It was a step up for Sarah, an opportunity to create a better life for her children, and she was determined to make the best of it. But in 1941, when she was just 47, she suffered a fatal heart attack that left her two young children, Zenaida and her brother Cleveland, orphans. Neighbors in Tacajó took them in.

Whether out of pity or necessity, the Cuban doctor agreed to let Zenaida take her mother’s place even though she was only 13, spoke halting Spanish and had never worked as a domestic servant. One day, Zenaida was cleaning a crystal bowl filled with candy when she noticed ants crawling inside. She knew that if the doctor’s wife saw the ants, she’d be fired. She remembered what her mother had told her about putting bread near the stove and did the same with the candy dish. The flames drove away the ants, but the heat shattered the crystal. When the doctor’s wife found out what happened she scolded Zenaida harshly and called her a stupid, stupid girl.

Zenaida swore she’d never be humiliated like that again.

When the doctor left his job, Zenaida worked for the new medic’s family. Her life continued that way, moving from family to family, secretly harboring a dream to one day become a doctor herself. When one of the families she worked for moved to Havana in 1947, Zenaida decided to go with them. She was 19 and believed life would be better in the capital. It didn’t take her long to realize that a young black woman with no education had no business dreaming of becoming a doctor no matter where she lived. After a few years in Havana she’d had enough, but instead of returning to Tacajó she decided to try her luck in the city of Guantánamo. She’d heard that the American Naval Base hired Cubans and treated them well, and more so if they spoke English.

Zenaida found work at a nursery school on the base. Every day she took a ferry across the bay to the American side, being sure to sit on the side of the ferry reserved for blacks. She made good money and she spent some of it on gold jewelry that she kept as insurance, just in case things did not work out. She caught the eye of a young cabinet maker from Haiti named Aristede Limonta who also worked with the Americans. He was dark and handsome, with a husky sex appeal that years later she’d compare to the American singer Barry White. They fell in love and moved into a small wooden house on the corner of Cespedes and Eighth on the south side of the city of Guantánamo. When Zenaida became pregnant she made a sacred vow to the Virgin of Caridad del Cobre, Cuba’s patron saint whose sanctuary sits on a hill outside the city of Santiago. If the baby is a girl, she promised, her name will be Caridad.

For a short time, Zenaida believed she had succeeded in putting the humiliation at the doctor’s house behind her, but there was trouble ahead. Aristede started making eyes at other pretty young women. Zenaida tried to ignore it. When her water broke, and Aristede hired a horse and buggy and rushed her to the hospital in Guantánamo. On December 18, 1956, she delivered the baby–a girl—but then the midwife told her another baby was on the way.

I can’t have another one, not now, she told the nurse. I’m having trouble with the father.

Trouble or not, she was having twins.

Ten minutes later, a second baby girl was born. For Aristede’s family, having twins was nothing unusual. His great grandmother María was said to have given birth to five sets of them.

Seventeen days before the twins were born, Fidel Castro and 81 of his rebels had beached an old American yacht called Granma on an almost impenetrable mangrove swamp on Cuba’s southern coast. It was the calamitous start of their armed struggle to overthrow Fulgencio Batista, Cuba’s dictator who, with the solid backing of Washington, had ruled for decades. Then, at the same time that Aristede was promising to help Zenaida care for her infant daughters, Batista was boasting that the trouble-making Castro brothers had been killed in the landing along with nearly all the invaders.

Both Aristede and Batista were lying.

Zenaida fulfilled her vow to the Virgin of Charity and named her first baby girl Caridad Luisa. She called the other Esperanza Caridad. Hope and Charity. Charity and Hope. By now she was well aware of Aristede’s womanizing, and she felt betrayed. But with twins to care for she was willing to turn her cheek and give him another chance. All four of them lived together for about three months. Then one night after he’d had too much to drink, Aristede hit her.

Hurt, angry, and feeling like she’d once again been humiliated, she put her babies in a basket and went around the tiny house grabbing what she could of their possessions. But the gold jewelry that she had scrimped to buy, that was supposed to be her insurance just in case something like this happened, was sitting in a cabinet on the other side of the bed, where the drunken Aristede was passed out. She couldn’t chance waking him and getting hit again. Or worse, getting into a fight over the babies.

Zenaida slipped out without the jewelry and took the girls to the house of one of her mother’s Jamaican friends. When the babies were a few months old, she tried to go back to work but on her first day she ran into Aristede on the ferry. He started yelling so everybody could hear, blaming her for running away with his babies and keeping him from seeing them.

Let me off, she shouted, and the ferry pilot slowed the engine. Back on shore, she sent a telegram to her brother, Cleveland, telling him to meet her at the train stop at Manguito, outside Tacajó, because she was coming home. She never recovered her jewelry and she never married, but she would always insist that Aristede had been the first and only true love of her life. Still, for decades afterwards, whenever she heard any song by Barry White on the radio, she’d leave the room.

A single mother, 27, with no job, no skills and no place to live, she was left with nothing but her two girls and her own determination that they would never be abused the way she had been.

Reluctantly, she went back to the house of Carmen Caro, the woman who had taken her in after her mother’s death, and knocked on the door. She was embarrassed to tell her that she had failed in everything she’d tried since she had left Tacajó years before, and now she had no one else to turn to. Carmen had a large family of her own, with many children –including a little girl they called Cuka--and grandchildren all living under the same roof. But she was a generous soul and made room in the big old house for them.

In the mountains not far from Tacajó, Fidel had revealed to the world that Batista had lied about the landing. He and most of the men with him had indeed been strafed as they wrestled through the mangroves, but once they gained their footing on the beach they managed to make it into the dense forest of the Sierra Maestra where they regrouped. Early in 1957, he called dozens of his followers together to finalize plans for an armed uprising to overthrown Batista, leaving somewhat vague just what would happen if, against all odds, they managed to usurp the dictator. Before that meeting started, Fidel talked to an American newspaper correspondent from The New York Times that his men had smuggled into the mountains. When the reporter, Herbert L. Matthews, returned to New York days later he wrote a series of sensational articles that revealed to the world not only that Fidel was alive, but that he was winning the war against Batista—a gross exaggeration in 1957. Matthews portrayed Fidel in glowing terms, painting him as a Cuban Robin Hood, a heroically impressive young lawyer with a scraggly beard who promised to restore constitutional government and hold elections.

Some of the fighting was taking place in the mountains around Tacajó, but Zenaida was too busy taking in laundry for mill workers and raising her girls to get involved in Castro’s struggle. But he and his movement were having great success attracting many followers, and by the middle of 1958, when the U.S. finally cut off arms sales to Batista’s government, there was little doubt that the dictator’s days were numbered. Early on the morning of January 1, 1959, Batista loaded a few planes with millions he looted from the national treasury and, with his family and a few aides, fled to safety in the Dominican Republic.

Like most Cubans, Zenaida rooted for Fidel, then just 32, as he took over the entire country. She believed him when he promised that he was going to make life better for all Cubans, regardless of their race or gender. When Fidel set up his national system of watchdogs called the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution, she became an active member. She also joined the Federation of Cuban Women founded by Raúl’s guerrilla wife, Wilma Espín. When the government opened a small health clinic inside the home of the former director of the sugar mill, she got a job mopping floors and changing sheets. It wasn’t much compared to her dream of becoming a doctor, but for her and her little family, it was a step up, a big one.

The Americans who had run the sugar mill scurried home when the mill was nationalized in 1960. The Cubans who took over made sure its bellowing smokestacks and daily rhythms continued to dominate life in Tacajó. They kept the phone system linking the home of every worker to the central office functioning and saw to it that the mill’s whistle bellowed at the start and end of every shift, a deep vruuuum – like a hole in a gigantic muffler--that, in the dim light of dawn, with roosters crowing and frogs croaking, woke Zenaida and the girls to the challenges of each new day.

They lived in a cuartería, a long row of 10 tiny apartments, each no more than a single room. The latrine was in the woods a few steps away. They were there when Hurricane Flora came crashing toward them in 1963. It was a powerful storm, one of the deadliest ever. By the time Zenaida heard the warnings on her little transistor radio, the wind and rain were almost on top of them. The clinic needed her, so she took the girls, not yet seven, out of the wooden cuartería and left them with a friend who lived in a sturdy masonry house near the clinic. The girls watched from the open front door as she inched her way up the wind-blown street toward the clinic, grabbing onto a bougainvillea fence to keep from being blown off her feet. Frightened that she might never come back, they tried to comfort each other through the long night. As the sky churned with gray clouds and the stars disappeared, Cary sang a song that Mr. Pedrozo, her fourth-grade teacher, had taught the children in chorus: Ask the stars if at night they see me cry.

When Flora finally veered off into the Atlantic, and Zenaida was allowed to leave the clinic, she took the girls home. Flora had completely flattened one end of the cuartería. The walls of their section were still standing, but the roof had been torn off and the heavy rains had soaked the big armoire that was packed with everything they owned. They gathered what they could save and, once again, moved in with friends.

As Tacajó rebuilt, Zenaida became a fixture in the clinic. In 1968 she enrolled in a training program for nurses’ assistants at a hospital in the city of Holguín. When the nine-month program ended, she returned to Tacajó with a new title and a plan for the future. In the local clinic where she once washed floors, she was now had a job as an auxiliary nurse. She came to be known, and feared, for ruthlessly giving injections to all, sticking everyone from the bravest to the most squeamish without the slightest hesitation or sympathy. But she also endeared herself to the people of Tacajó for the big heart she opened to everyone.

Copyright © 2020 by Anthony DePalma. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.