Chapter One

About thirty years ago (1), Miss Maria Ward of Huntingdon (2), with only seven thousand pounds (3), had the good luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park (4), in the county of Northampton (5), and to be thereby raised to the rank of a baronet’s lady (6), with all the comforts and consequences of an handsome (7) house and large income. All Huntingdon exclaimed on the greatness (8) of the match, and her uncle, the lawyer (9), himself, allowed her to be at least three thousand pounds short of any equitable claim to it (10). She had two sisters to be benefited by her elevation; and such of their acquaintance as thought Miss Ward and Miss Frances quite as handsome (11) as Miss Maria (12), did not scruple (13) to predict their marrying with almost equal advantage. But there certainly are not so many men of large fortune in the world, as there are pretty women to deserve them (14). Miss Ward, at the end of half a dozen years, found herself obliged to be attached to the Rev. Mr. Norris (15), a friend of her brother-in-law, with scarcely any private fortune, and Miss Frances fared yet worse. Miss Ward’s match, indeed, when it came to the point, was not contemptible, Sir Thomas being happily able to give his friend an income in the living of Mansfield (16), and Mr. and Mrs. Norris began their career of conjugal felicity with very little less than a thousand a year (17). But Miss Frances married, in the common phrase, to disoblige her family (18), and by fixing on (19) a Lieutenant of Marines (20), without education, fortune, or connections (21), did it very thoroughly. She could hardly have made a more untoward choice.

ANNOTATIONS (on facing pages):

1. This is the only time that Jane Austen states at the outset of a novel how many years earlier her story began. One reason is that this novel provides by far the longest narrative (lasting several chapters) of the events leading up to the main action, including the heroine’s childhood. As usual, Austen is careful and accurate in her dating. The main action begins approximately twenty-seven years after this opening event and transpires over one year. The concluding events sketched in the last few pages would logically span about two years and possibly a little more. For more detail, see the chronology, p. 853.

2. Huntingdon is a town in eastern England and the county seat of Huntingdonshire. Since the time of this novel Huntingdonshire has been absorbed into the county of Cambridgeshire.

3. In most wealthy families, women were allotted a fixed sum as their inheritance. It would serve as a dowry and go to her husband upon her marriage.

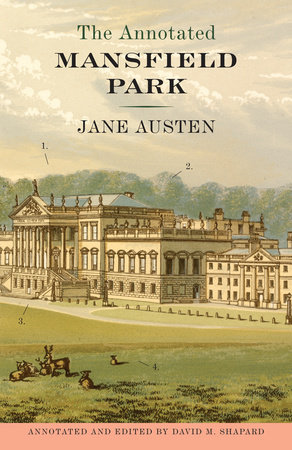

4. Grand homes were always given formal names. Many names included the word “Park,” for estates normally had ample grounds, and the name designated the grounds as well as the house.

5. The county of Northampton, or Northamptonshire, is in the Midlands of England; it is to the immediate west of Huntingdonshire. Jane Austen, who was never in Northamptonshire, probably set her story there because its distance from Portsmouth, the home of the heroine, serves the plot by making travel between the two places difficult. Similar considerations determine her choice of settings for other novels. For these locations, see map, p. 882.

6. A baronet was the highest rank in Britain below the aristocracy or peerage. It was a hereditary knighthood, which gave the holder the right to be known as “Sir” and his wife the right to be known as “Lady” but, unlike the peerage, conferred no legal or political privileges. Baronets and peers, as well as the untitled gentry who ranked just below them, derived most of their wealth from large landed estates, usually with grand residences like Mansfield Park at the center. This landed elite dominated British government and society.

7.

handsome: large. The word could also refer to the house’s attractiveness, but in this context it probably refers mostly to its size.

8.

greatness: social eminence. This and its attendant privileges are what is

primarily meant by the “consequences” of the match.

9. “Lawyer” at this time could mean either a barrister, who could try cases in court, or an attorney, who could not. The uncle is likely a barrister, for barristers were considered gentlemen (for what this means, see p. 17, note 67) while attorneys were looked down upon socially; having an uncle who was an attorney would have been a formidable barrier to marrying a baronet.

10. Marriage choices among the wealthy were so heavily determined by considerations of fortune and social rank that people had a clear sense of how much wealth on the wife’s side would normally be required to attract a husband of a specific social and economic level. Lawyers would be particularly aware of this, for much of their business involved negotiating and drawing up the complicated financial settlements that elite marriages involved.

11.

handsome: attractive. The word is frequently used in Austen’s novels to describe women, with no masculine connotation intended.

12. “Miss Ward” is the eldest. The oldest unmarried daughter in a family was referred to as “Miss + last name”; her younger sisters were referred to as “Miss + first name,” with the last name sometimes added. Later we learn that Maria was the next oldest, and Frances (or Fanny) the youngest (p. 734—the latter is called “some years her [Lady Betram’s] junior”).

13.

scruple: hesitate.

14. This basic truth manifests itself throughout Austen’s novels, and—along with women’s urgent need to marry due to the absence of alternative careers—provides much of the novels’ dramatic tension. The reference to a woman’s prettiness underlines the importance of looks as an asset. It is almost certain that her looks were what allowed Maria to make such an advantageous marriage, for, as is soon revealed, she has almost no other attractive qualities.

15. “Rev.,” short for “Reverend,” indicates he is a clergyman. Clergymen were central to English rural society at this time. Jane Austen’s father was a clergyman, as were two of her brothers. Clergy tended to be closely connected to the landed elite, and usually ranked next in status in the rural hierarchy. The phrase “obliged to be attached” indicates that Miss Ward married for the sake of her husband’s social and economic position rather than for love, which was not unusual.

16. This living is the position as clergyman for Mansfield parish, which comes with a regular income. England was divided into parishes, which were units both of the church and of local government; each parish had a church and a clergyman belonging to the Church of England. The official state church enjoyed legal privileges and was where most people in England worshipped, including virtually everyone in rural areas like this one. In towns and cities, more people belonged to other denominations, though, while generally able to worship freely, they were still obligated to contribute to the official Anglican Church. The power to appoint someone to a church living was frequently in the hands of wealthy landowners, and it was standard for them to appoint friends and family members. Jane Austen’s father was appointed to his living by a cousin, which allowed him to marry and start a family. For more on the system of church appointments, see p. 47, notes 3 and 6.

17. This is a very comfortable income, though not nearly as grand as Sir Thomas’s (which is never specified) undoubtedly is. “Conjugal felicity” was a common expression of the time, in this case used ironically, given the real motives behind the marriage.

18. This society emphasized people’s obligations to their family, which included taking into account the family’s wishes and interests in one’s marital decisions.

19.

fixing on: choosing, selecting.

20. The Royal Marines was a corps of soldiers who were trained like army soldiers and had similar uniforms and weaponry, but were attached to the navy. Virtually every naval ship had a contingent of marines, who existed to participate in landing parties that were sent ashore, to assist in hand-to-hand combat when a ship directly grappled with an enemy ship, and to maintain order and discipline. Commissioned military officers were considered gentlemen, but those in the marines were lower in status than army or navy officers. One reason was that, whereas commissions in the other services either had to be purchased or required years of experience, neither was the case in the marines, so those seeking marine commissions frequently had humble backgrounds and poor qualifications. This, plus the fact that lieutenant was the lowest officer rank and promotion was difficult, would make such a figure an undesirable husband for a woman from a family that could give its daughters a decent dowry and whose other daughters had married a baronet and a clergyman with a good living.

21.

connections: relations, family ties. Such ties were highly important, both for social prestige and for the practical benefits they could confer. This man’s lack of them, along with his lack of education and private fortune (he would receive only a modest salary as a marine lieutenant), would add to his undesirability from the perspective of the bride’s family.

Copyright © 2017 by Jane Austen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.