In My Mother’s Arms by Mary Jane CoppsThe “ordinary” family is capable of inflicting much pain upon its children. Pain which, by necessity, moves inward, creating adults who must either unravel their secrets or perpetuate a legacy of betrayal.

-- Jan Austin, psychotherapistI am startled awake by the quick, cold hands that hoist me to her shoulder. She impatiently pats away my instinctive cry of distress.

At three, sleep was a place I went to, like going to the playground with my sister, or running in the backyard with Prince, our cocker spaniel. Sleep was even a favoured outing, always surprising me with who, or what, would show up to play.

I loved surprises. I believed in them, saw them as a necessary part of life. My days were filled with looking for them. Head down, I would walk along sidewalks, intent on finding a shiny coin or sparkling jewel. Whenever possible, I would turn over rocks and dig in the earth beneath, sure a treasure was awaiting me. And always, I pulled at the pockets of adults, convinced that the clinking I heard was something they were carrying as a gift, just for me.

So on this night, as the sliver of light slashes across my tumbled crib, and her fragile hands wake me to darkness, I can ignore my siblings’ sudden silence and fill my sleepy head with thoughts of Santa Claus.

In my house, midnight Mass distorted the reality of Christmas morning. My parents and brothers and sister would return home hungry, ready to get on with the opening of gifts, and I would be wakened to join them. I suspect that my mother, faced with the day’s prospects of too many in-laws and the endless details of the holiday meal, simply wanted to get something out of the way and pushed to establish this Christmas-in-the-dark tradition.

But it isn’t snowing. Perhaps the Easter bunny, then, or maybe my birthday. I snuggle deeper into her neck, closing my eyes tightly, for it is bad luck to ruin a surprise.

I’ve inherited my reverence for gift giving from my mother, a devout orchestrator of holidays and celebrations. These hallowed events were staged in one of two places, depending on the occasion. The living room couch, a much-protected piece of furniture, elaborately displayed the wares of Easter, St. Patrick’s Day, Valentine’s and birthdays. Always, I would build up the moment of surprise by walking down the stairs facing the wall, averting my eyes until the last possible second from the splendours that awaited me.

Sweaty from slumber, I cling to her coolness as she carries me down the stairs. Once in the living room, I push myself away from her shelter and look toward the couch in eager anticipation. It is empty. Unsettled, but not deterred, I close my eyes and once again set my drowsy hopes on Santa Claus.

Christmas was truly fantastic. The den, a large addition at the back of the house, became a holiday shrine. In one corner stood the magnificent tree (Scotch pine was her favourite) with lights, fragile decorations, aged tinsel, a golden angel and, of course, a circle of brightly wrapped gifts. Stockings hung from the top of a built-in bookcase, bulging with candy and the unwanted but necessary tangerine. And beneath them, the unwrapped deliveries from the North Pole. All this was held from view by heavy, brown brocade drapes that shut the den off from the dining room. Opening these drapes required her permission.

I feel the presence of my siblings as we reach the dining room and pop my eyes open in delight. All significantly older than I am, my two brothers and my sister are my playmates, my caregivers, and I love them fiercely. They stand huddled together near the kitchen door, looking not at me but at my mother. They do not make a sound. Behind them I see the open drapes and know for certain this is not about Christmas.

I must have seen their terror. I must have sensed her anger. But I had already chosen my role in this house, to remain hopeful long after it was prudent. My desire for a gift would not be quelled. Perhaps it was what saved us.

Once we are in sight of the other children, her voice rings high and loud above my head. This is her never-ending-flurry-of-words, all racing out of her mouth, bumping into one another, falling together and never making any sense -- at least not to me. But the others seem to understand. They turn in unison and enter the kitchen. From behind, she shoves each of them toward the stove.

If I had not been struggling against the mist of sleep, I might have seen her eyes, wide with panic and veiled with the glaze of prescription drugs. If I had been a little older, I might have smelled a day’s alcohol on her skin and heard the madness of her demand.

She is asking her children for proof of their loyalty, their unshakeable love. She gathers us around the stove, my brothers on her left, my sister on the right and me still in her arms. She turns the large front element on high, the electricity crackling to life and slowly changing the colour of the black coil.

“If you love me,” she says, “you will move your hand toward this element until I say stop.”

Her voice booms and bounces in the quiet kitchen. My siblings squirm. I remain mesmerized by the brilliant spiral below me.

“You first,” she says, nudging my sister with her elbow.

The shaking hand of my eleven-year-old sister begins a descent from its highest height toward the glowing orange element.

I am annoyed. I know about going first -- about opening the first present, being served the first plate, getting the first piece of cake. As the youngest, and very much the baby, going first is my place, my territory in a crowded household. Besides, I have been looking for a surprise and this sun-like object must be it.

With the agility and speed of a three-year-old, I wiggle and lunge, diving toward the burning element.

My sister’s hands catch mine. She pushes me back, toward our mother. My oldest brother moves quickly, stepping between us and the stove, clicking off this evening’s source of pain.

I giggle and laugh. I think we have invented a new game to play together, a type of dance, perhaps. My sister takes me from my mother’s trembling embrace. The speed words have stopped. Tears slide down her face, and she mumbles apologies without pause. My brothers cautiously walk her up the stairs, their footsteps creaking toward her bedroom. I sit with my sister in the kitchen. Held within her tight embrace, I listen to the wild rhythms of her heart.

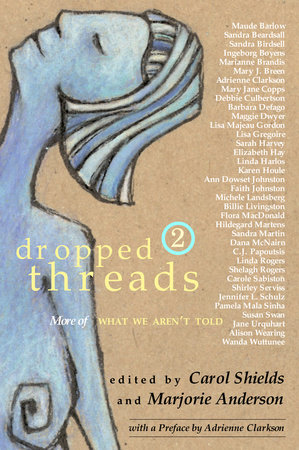

Copyright © 2003 by Mary Jane Copps. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.