OLD GLOBE

For her big birthday

we gave her (nothing less would do)

the world, which is to say

a globe copyrighted the very year

she was born—eighty years before.

She held it tenderly, and it was clear

both had come such a long way:

the lovely, dwindled, ever-eager-to-please

woman whose memory had begun to fray

and a planet drawn and redrawn through

endless shifts of aims and loyalties,

and war and war.

*

Her eye fell at random. “Formosa,” she read.

“Now that’s pretty. Is it there today?”

A pause. “It is,” my brother said,

“though now it’s called Taiwan.”

She looked apologetic. “I sometimes forget . . .”

“Like Sri Lanka,” I added. “Which was Ceylon.”

And so my brothers and I, globe at hand, began:

which places had seen a change of name

in the last eighty years? Burma, Baluchistan,

Czechoslovakia, Abyssinia, Transjordan, Tibet.

Because she laughed, we extended our game

into history, mist: Vineland, Persia, Cathay . . .

*

She was in a middle place—

her forties—when photos were first transmitted,

miraculously, from outer space.

Who could believe those men—in their black noon—

got up like robots, wandering the wild

wastelands of the moon,

and overhead a wholly naked sun

and an Earth so far away

it was less real than this one,

the gift received today—

the globe she’d so tenderly fitted

under her arm, like a child.

*

Finally, there’s cake: eight candles in a ring.

. . . Just so, the past turns distant past,

each rich decade diminishing

to a little stick of wax, rapidly

expiring. I say, “Now make a wish before

you blow them out.” She says, “I don’t see—”

stops. Then mildly protests: “But they look so nice.”

We laugh at her—and wince when a look of doubt

or fear clouds her face; she needs advice.

Well—what should anyone wish for

in blowing candles out

but that the light might last?

THE BIRTH OF INJUSTICE

Meandering Neandertals

keep bumping up against

the glacier’s high, invasive walls,

whose blackened snout

comes down to eat the ground underneath their feet.

Which is the way now?

What else but hunched despair’s

narrowing valleys, this gathering

feeling of everything

constricting?

It’s an old notion, nearly sensed

from way back when: somehow,

this exorbitant venture of theirs

—Life—isn’t working out.

She’s a brooder, this one,

on her rock, who once or twice, or thrice

(no words for numbers yet),

has laid a child to earth. They take

the tiny body from your arms and it goes

down into a cold mouth we make

ourselves, digging out the shape.

The ice

eats, the earth eats, and having set

her haunches on a rock, she ponders the light:

it’s dawn, or dusk, no language for

origins or ends, and yet the sun

is moving, and in her blood she knows

always their dwindling journey has been far

too brutal: something’s not right.

This big-boned figure who

subsists chiefly on cattails she praises

from the numb gray sand

of a half-frozen pond

prefers of course

the soft and steamy organs of horse

or aurochs, when those are in hand—

not often enough.

Not often enough, days

warmly warm, all the way through,

when the wished sun rises

up in your chest with the blaze

of honey on the tongue, for you the ache

and sting of it, sweet beyond

any sounds a mouth might make.

REMOTE MIDNIGHT

Icelandic Mouse As, safe in its hole,

The field mouse quakes when the hawk

Soars across the sky,

So the candle, indoors, shakes

When the wind goes howling by.

Kenyan Lion . . . The leaves, too, quiver

At the roar of a creature

Whose gullet’s vaster

Than that lair where the battered

Blood-streaming sun’s retreated.

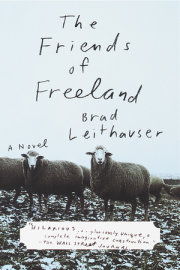

Copyright © 2013 by Brad Leithauser. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.