1. The Heart Doctor As a boy in Usulután, in eastern El Salvador, Juan Romagoza grew up knowing that one day he would become either a doctor or a priest. The church called first, with the casual force of inevitability. The signs of a future life in the Catholic ministry were everywhere, starting on the street where he lived, in a Spanish colonial house with his parents, eight siblings, grandparents, an aunt, and an uncle. It was just around the corner from the city's main church, a simple but imposing building with two towers and a broad front staircase. Early each morning, the family attended mass. On Sundays, at the house of Juan's great-grandparents, the bishop would often visit for lunch. He was a stiff, corpulent man, who dressed in a flowing white robe. Jewelry covered his hands and neck. The adults used to summon Juan and the other children to kneel before him and kiss one of his rings. The whole family was

muy beata, neighbors used to say; they were church folks, pious in the extreme. In 1964, when Juan was thirteen, he announced to the family that he wanted to leave home to attend the seminary, in the nearby mountain town of Santiago de María. "One less mouth to feed and one more saint in the family," his mother said.

It didn't take him long to realize his mistake. Juan loved Usulután's pulsating sense of community; neighbors were linked together in an atmosphere of friendly complicity. The seminary felt closed off and drained of communal life. It was also treacherous in ways he hadn't foreseen. At night, he learned to wrap himself tightly in his bedsheets and blankets to avoid the attentions of one priest who was notorious among the young seminarians for making rounds after dark. When Juan came home, six months later, he not only refused to return to the seminary; he thought he might be an atheist.

Medicine became Juan's enduring religion. As with the church, his attraction to it ran deep, dating from the day he watched his fifty-two-year-old grandfather die of a heart attack. Juan was eight at the time, and he clung to his grandfather's side while the family waited three hours for a doctor to arrive. Untreated ailments addled other family members. They developed chronic debilitations-blindness in an eye, a bad limp, a lifetime of stomach trouble. "A doctor is really a kind of high priest," he told his family as he grew older. The profession answered to a higher calling.

Juan was short and scrawny, with wispy dark hair, olive skin, and alert eyes. Quiet charisma hung off him like a loose shirt. At school, and on the streets, he always found his way to the center of group activity. There were soccer matches and neighborhood pranks in his boyhood, and, as he got older, demonstrations organized against local authorities. The prevailing attitude in town was a ready sympathy for the

obreros and

campesinos in their midst-the workers and the peasants-and a corresponding coolness toward men of overweening authority. Church figures were a sometimes polarizing exception.

Juan's mother was a seamstress, his father a gym teacher. They could only afford to send one child at a time to college, but Juan, who was his school's valedictorian, earned a scholarship from the Casa Presidencial, in San Salvador. In 1970, he arrived at the University of El Salvador to study medicine, a seven-year degree that wound up lasting ten.

El Salvador's politics were dominated by an alliance between the business elite and the armed forces, which grew increasingly turbulent during the 1970s as the broader public rebelled. Protests and protracted worker strikes led to government crackdowns. The university kept closing for months on end. During these stoppages, Juan would volunteer in different hospitals across the country-in places like Usulután and Sonsonate, where he knew people-and this way got some training in before school reopened. He had already chosen his subspecialty. He wanted to be a heart surgeon.

The surgery residency came near the end of his education, one of the last rotations before completing the degree. This was why, on a hot, humid evening in February 1980, Juan found himself at the San Rafael National Hospital, in Santa Tecla, twenty miles west of San Salvador. It was his fourth week at the facility, and he was beginning to feel comfortable there. The building was old but charming; a single story, it was organized around an interior courtyard, with a facade made of stone painted white and blue, the national colors, and lined with deep-set windows and decorative columns. Like any medical resident, Juan spent more time at the hospital than he did at the garret-size room he rented in San Salvador. He worked long hours and took naps where and when he could, in between assignments assisting with surgeries and running down doctors' requests.

At around five p.m. a gurney came crashing through the doors of the emergency room. On it was the bloodied, unmoving body of a student protester. Juan later learned the identity of the patient. He was the leader of an association of high school students called the Movimiento Estudiantil Revolucionario Salvadoreño (MERS), a junior offshoot of the teachers union. It frequently mobilized in anti-government demonstrations around the capital.

The student had been strafed in the neck and stomach by police gunfire and rushed by his friends away from the scene of the shooting to his parents. But they had all been reluctant to bring him to a hospital. The state security forces had a reputation for searching hospitals after violent incidents and dragging out injured protesters. Often, these protesters would never be heard from again, or else their mutilated bodies would be deposited a day or two later on a street corner as a warning to their confederates. The family had decided to take him to San Rafael because the hospital was just outside the city and therefore, they hoped, beyond the immediate watch of the police.

For four hours, Juan assisted with the surgery, and eventually the student was stabilized and transferred from the operating room. At San Rafael, the intensive care ward was a single rectangular-shaped hall, with beds arranged in rows and cordoned off from one another with curtains. Juan pulled a chair up to the patient's bed. He checked his blood pressure, adjusted his catheter, and recorded his vital signs. It was after ten p.m. by the time Juan was done with the first round of tasks, and the hospital had grown quiet. Only Juan and a nurse remained in the ward. Sitting upright alongside the bed, he drifted off, lulled to sleep by the sound of the nurse padding along the tile floor.

A thumping sound jolted him awake a few minutes later. The intensive care ward was in the eastern wing of the hospital, and the emergency room and parking lot were on the western side. It took Juan a few seconds to realize that he was hearing the rhythm of soldiers' boots marching the length of the hospital, down the colonnaded archway, toward where he sat with his patient.

"They're coming for you," he found himself saying aloud to the boy sleeping beside him. He rose and spotted the nurse, who was standing up, ramrod straight. Before either of them could do anything, there was a loud, guttural shout. Juan wheeled around to see a group of a half dozen men masked in balaclavas and armed with rifles and pistols coming through the door. Some wore the green uniforms associated with the national security forces; others were dressed like civilians.

"Get on the ground. We'll shoot you if you try to get up," one of them yelled. Juan dropped to the floor. He kept his eyes on their boots as the men walked toward his patient, stopping right in front of the bed. They knew their target. A member of the hospital staff had likely tipped them off.

Without saying a word, the men opened fire. Spent cartridges rained down around him, pinging off the floor. The bed rocked and rattled from the force of the bullets. Then, just as swiftly as they had entered, the gunmen left, marching off the way they had come.

"Did they leave?" Juan called out to the nurse. She was in her fifties, calm and experienced, but she was crying. "I think so," she replied. He jumped to his feet and gratuitously grabbed the wrist of his patient to feel for a pulse that wasn't there. Juan's eyes were on the window, and he moved toward it cautiously before looking out. In the parking lot, he could see a fleet of green trucks before their taillights flickered on-a flash of red in the dark-and they peeled out into the night. Juan began picking up the cartridges, which were still hot to the touch.

"Why are you taking those?" the nurse asked.

"To remember this," he replied.

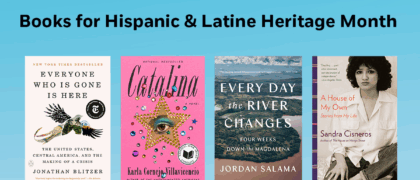

Copyright © 2024 by Jonathan Blitzer. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.