IntroductionTo meditate on a name, a face, or the sound of someone’s laughter is an intentional act of remembering, or an attempt to resist forgetting. Remembering, or being reminded of, helps to rework our understanding of our identity by giving us insight into the people and places that shape us. Through photography, particularly family pictures and snapshots, we get a better sense of our people, our histories, and our stories—we are able to add to, or cultivate, a language for the parts of our lives that cannot be fully known, even if felt.

A series of snapshots helps illuminate the stories we tell—and are told—about our lives. The intimacy held within these types of pictures gives us the agency as Black people to show up and to be witnessed as our full selves through our mannerisms and body language, often without an outside influence, gaze, or imposed restriction. With snapshots, anything goes, and historically they have served as a quick and affordable way to document the celebratory (and the mundane) moments in one’s life. I consider snapshots the most authentic storytelling medium in the written and visual language—they require very little technical skill yet can render some of the richest and most beautiful stories. It’s no wonder that snapshots are memorialized in family photo albums and passed down as evidence of lives, fully lived, throughout generations.

In many families, each generation has a designated member that curates their family photos. The work of this curation is a labor of love, and an impressive skill not to be taken lightly. Family photo albums are magical, yet familiar. For many, they are home. They are spaces to find comfort, strength, and even escape. An album is a place where you are met with faces you know, and perhaps some you come to know—faces that reveal and inspire stories and confessionals. They force us to reflect on the various ways that we have appeared—and faded away—throughout the years. The family member who is called upon to gather and curate these images is doing their family—and our collective histories—a great service by pulling together the truth of our existence as people.

One of my most treasured activities growing up was flipping through the pages of our family photo album. Ours was meticulously curated by my dad, Edwin, who thoroughly enjoyed being our designated photographer. I never saw my dad drop a roll of film off for developing and rarely saw the envelope with developed photographs and negatives. I never caught him rearranging the photographs into the album, weaving them through cut-out magazine or newspaper clippings in lieu of writing the date or location alongside the image or on the page beside it. It existed—like magic. Fifteen years after his death, I am amazed at the power of being able to relive these moments and consider his intentionality today. Because of his passion, I am able to revisit and trace our story, to try to see it like he did. Each time I look back, I pick up on something new that I hadn’t noticed, or perhaps didn’t previously have the language for.

Through the evolution of technology, we are now able to bring these snapshots into the digital realm, where we can share them with our relatives over group texts and social media. This practice allows us to create, cultivate, and share space within online communities and form kinships that reflect a collective familial experience—from things we recognize within our own families and our commonalities, to our differences and the ways our households and traditions are unique. It gives us space to discuss family archival methods, teach one another new ways of storytelling using family keepsakes, and exchange techniques to help us create and sustain our own personal archives. These digital communities help us connect with long-lost relatives while identifying a new generation of archivists, storytellers, ethnographers, and historians. It’s a way for us to create new systems to avoid archival loss and erasure.

I recognize that not everyone has access to family photographs, or stories. In many families, particularly Black families, tangible keepsakes have been lost, destroyed, or taken over the years, leaving future generations with the task of piecing together misplaced histories. This can be difficult to reconcile, particularly during a time when there are so many people sharing moments from the past in digital spaces. Those who find themselves without family photos and keepsakes can often find joy and comfort in those of other families. Even in the images of people we don’t personally know, we can find so many familiar figures and moments: kids playing in the yard, parents dressed up for an occasion, family gatherings, and celebrations. These images prompt our own memories, allowing us access to both our individual and our collective pasts.

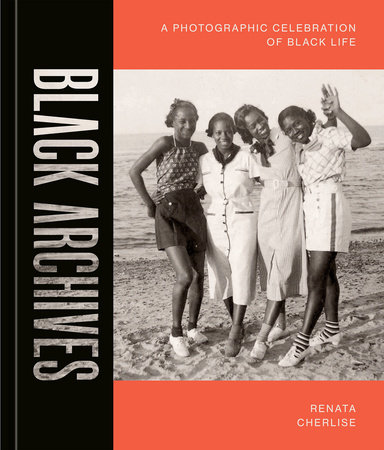

Black Archives: A Photographic Celebration of Black Life explores familial archiving practices, and how we experience kinship and recognize one another through a visual language of the Black experience. This book also fills the chasm of silence between the photos of where truth lives, and the black hole of the unknown. The images in this book were sourced from the Black Archives community and archives held in various institutional repositories. In the spirit of trying to create a collective family album about Black life, I issued a call for photo submissions and received hundreds of incredible family photos from Black folks all over the world. People shared what they knew about the photos, but a lot of the information about the people, locations, and time periods captured was not known or had been lost to time—such is the nature of family photo archives. As such, the scope of information provided about the images in this book varies: some photo captions contain names, locations, and dates; others might only contain locations, names, or may only have estimated dates. This inconsistency is to be expected given the nature of this work, and to some degree, may heighten the experience of this book as a collective family album.

It is my desire that the photographs collected here honor the many stories that were lost in transition, and that by sharing these archiving practices, I can help amplify the stories we do have through collective kinship.

Copyright © 2023 by Renata Cherlise. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.