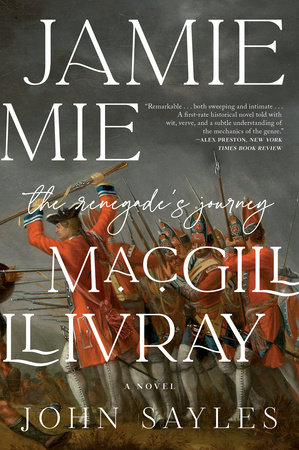

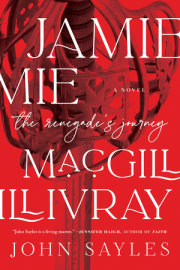

CULLODEN MOOR The mare slips, climbing the rain-slick hillside, white puffs huffing from her nostrils in the frigid evening air. Jamie MacGillivray, new-bought plaid draped over his head, leans forward in the cracked saddle, cooing to the beast in Erse. There are no trees. He knew this, of course, remembered it, but the bleak nakedness of the hills is still a shock after so much time away. Sudden scooting of dappled feathers to his left, but the mare is too weary to startle. Easier to snag a grouse in one’s bare hands than to find the Laird Lovat if he wishes it not. At what the gentry call Castle Dounie, the resident Fraser secretary condescended to inform Jamie that the Auld Fox was not yet so vexed with age as to return straight to his clan seat after a narrow escape, and that even if he was there, the quest was pointless. But Jamie is a go-between by profession now, and the job requires patience. The more accomodating Fraser, who attends the Prince, cautioned Jamie of Lovat’s calculated evasiveness, his eel-like ability to change direction, even shape, but stressed that he is the key to success in the impending carnage—then whispered the name of the great chieftan’s most likely hideaway.

Jamie, cold and sodden, is unsurprised that no Highlander he’s asked since has been willing to cede him the exact location, or even admit that such a place as Gortuleg exists. His only guess is that it lies somewhere here on the northern shore of Loch Mhòr, possibly over the next hill—

Jamie presses his knees tight to the mare’s steaming flank. They gain the crest as the rain hardens to something like sleet, then pause to survey the other side, and there it lies, just below, chimney smoke blown sideways from a middling, whitewashed cottage left deceptively unguarded. Turf smoke, by the smell of it—the Auld Fox must save his kindling for honored guests.

A few bodies move about the cottage, none looking up the hill as Jamie allows the surly mare to rest. They have surely kenned his coming for an hour at the least—even with the young and vital away in arms, Frasers are not to be caught unawares—

Je suis prest their motto. Jamie has seen Lovat only once, he and Dougal as boys fishing in the Moy Burn when the procession came through on a hunt to the north, the laird with a parade of his henchmen. The

óstair first, leading the great man’s stallion with a trio of young bodyguards trotting alongside, keeking the hills for danger, and then the sword bearer and the baggage man and the standard bearer, wavering as his flapping banner caught the wind and pulled him backward, and the piper, striding with his nose in the air, his own gillie shuffling behind with the bulky instrument draped upon him like a many-armed sea creature, and then the portly Auld Fox himself, legs outsplayed, riding the shoulders of his ruddy-cheeked

casflue across the frigid water.

Je suis prest, announced the banner, letters on the belt that circled the buck’s head,

I am ready, but they knew before they read it, Jamie and his brother standing with mouths gapped wide and poles forgotten in their hands. It was in the man’s face, everything they’d ever heard of him, as he spread his wide, jack-o’-lantern grin and nodded to one of the half-dozen

luchd tighe trotting to the rear with hands on their swords, and that ready young man flipped a tarnished shilling that Dougal snatched before it hit the water. Laird Lovat with the grin of a wolf, eager for whatever life might place before him.

Jamie prods the mare, and they start down the hill.

Tweedie watches from the door as the stranger hands Rhory Bain the reins to his mount and steps forward. It is a tall mare, none of your shaggy little Galloways for this lad, who announces himself in Erse with a foreign lilt to it and waits in mud-caked boots and wet woolen breeches. Tweedie can hop it when he desires, but now drags his ruined leg emphatically across the cold plank floor to advertise the intrusion. It always hurts worse in the cold. Though at times the Laird will curse Tweedie’s slowness and his clumsiness and the leaden scrape of his gait, and joke that if this crippled oaf is truly his blood the Frasers are doomed for certain, the Auld Fox is a great man, and they all, from the royal cousins to the lowest wandering thrasherman, strut prideful in the world to claim him as their chief.

The great man is on his chamber pot when Tweedie announces the visit.

“A MacGillivray, is it?” says the Laird, the meaning of his smile yet to be revealed. “Lead him in. And ale for the two of us.”

Tweedie moves a mite quicker to cross the excuse for a hall and calls the stranger in, telling him to wait by the door. He pours twopenny from the bucket into a pair of tankards on the small table, then stirs the fire and hitches out past the visitor to the yard, only a thin, cold rain to contend with now.

Rhory Bain is watching the stranger’s mare eat hay.

A MacGillivray, Tweedie informs the hostler, speaking Erse. One I’ve never seen before.

Another young man gone a-kingmaking, snarls Rhory Bain, not one to waste a soft word on a two-legged creature.

He wore no cockade.

He reeks of it. What else would stir a man out in this weather?

Tweedie moves to peer back inside. The men are standing at the table, drinking ale. He strains to listen.

They’re talking Saxon.

Rhory Bain scowls. No good will come of it, he says, same as the Last One.

They are both old enough to remember the Last One, the ’15, Tweedie still whole then and mustered to march back and forth across the country with never the occasion to fight.

The Laird knows what’s right, he says.

He does indeed. That one—Rhory jerks his shaggy white head toward the doorway—will leave on the same horse he arrived on.

The Auld Fox stands by the fireplace, eyes gleaming red. “Spare yer tongue,” he says, the burr of the Highlands a conscious filigree to his English. He’s at home here, not preening for the peers in London, wig left snug in its powdered box. “Ma mind is fixed.”

Jamie stands back from the flickering light, his bonnet wet under his arm, épée de coeur buckled at his hip, feeling the cold of the room at his back. “Ye’ve a son with the Prince,” he says.

“And twa mair in the scrape with the Royal Fusiliers, standing by King George. Them that’s left tae me are needed fer the plough.”

The notorious master of intrigues, thinks Jamie, careful to gird both his flanks years ahead of Prince Charlie’s impetuous fling at the throne.

“The French are coming with arms and men,” he ventures—

“The French!” smiles the Auld Fox. “The French have been coming fer thretty years noo, and I’ve yet tae keek a mon of ’em in the flesh.”

“I’ve ainly just been with the Prince—”

“I smelt it when ye strode in.” The Auld Fox had been as canny in the ’15, promising both parties the support of his clansmen but never quite joining either, conniving to hold on to nearly all his ill-gotten estates after the Defeat.

“T’will gae hard with ye when we’ve won,” says Jamie, a statement rather than a threat.

“I’ve ma son with yer lot tae plead fer me.”

“If he survives the fighting.”

The Auld Fox shifts his head, eyes shadowed now. “Enough shall be lost,” he says quietly, “withoot I add tae the sorra.” He steps toward Jamie, looking him over from boots to crown. Snorts. “Yer father was as fu’ of the Cause in his ain day—he’d hear nae counsel. If he’d listened, ye’d no be ferrying coals fer the MacIntosh.”

The Auld Fox is as wide as he is tall, powerful, excesses of table expanding his girth while those of the court and the bed-chamber still frolic in his wicked eyes, his constant smirk. Jamie notices that the heavy chairs set at the table have rings below the arms, rings to fit the poles with which, after a night of toasting one king or another, the neighboring laird and the three-bottle men and perhaps the Auld Fox himself, mumbling and cock-eyed, are carted off to sleep.

“There is Honor tae be considered.” Jamie hears his echo in the stone cottage. No claymores cross over the mantelpiece here, no coat of arms like the secretary Robert Fraser stood before at Castle Dounie. This is the lair of a chief in exile, something better than a croft or a cave, but only meant as shelter till the outcome of the great struggle is known.

The Auld Fox smiles again, eyes crinkling into slits. “Aye, the French are great uns fer Honor.”

And then the lame house gillie, breath wisping ghostly in the cold as he enters, informs them that there is a messenger from Inverness.

Copyright © 2023 by John Sayles. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.