INTRODUCTION TO THE 2023 EDITIONRobin D. G. Kelley “It seemed un-American to depict the evils of slavery and disloyal to talk about African American people fighting for freedom against whites. Omitting, neglecting, or suppressing the facts of slave defiance became a lasting American tradition.” William Loren Katz wrote these words in the introduction to this marvelous book over three decades ago. As I write this foreword in the summer of 2022, Katz’s words ring truer now than when he published

Breaking the Chains thirty-two years ago. We are living through a new wave of intellectual McCarthyism. Driven by white nationalism, the latest wave of attacks on multicultural education is shrouded in racially coded language of “anti-wokeness.” The Right is using the law and bullying tactics to declare war on “critical race theory” (CRT)—which has become a stand-in for liberal multiculturalism—banning books and curricula dealing with racism, sexism, or gender identity. Moms for Liberty in New Hampshire offered a $500 reward for turning in teachers who violate the state’s anti-CRT law. In April 2022, Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed into law the Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees Act, or Stop WOKE Act, which prohibits teaching anyone that they bear “personal responsibility for and must feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress because of actions committed in the past by other members of the same race, color, sex or national origin.” Iowa governor Kim Reynolds signed a similar bill that criminalizes teaching anything considered to be “divisive,” including subject matter that might make “any individual . . . feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of that individual’s race or sex.”

The “individuals” these laws are designed to protect are white kids who presumably would feel shame and guilt if they had to confront the history of American racism. (The feelings of Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous children are never considered.) Let’s ponder the implications: if, as Katz observes, acknowledging the history of slavery and the heroic struggle to end it is “un-American” and “disloyal,” then defending slavery and racism is the “American” and patriotic thing to do. Absurd, you say? Consider the fact that there is no commensurate movement to ban books that explicitly promote racism: for example, Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia; works by prominent “racial scientists” and eugenicists such as Dr. Josiah C. Nott, Louis Agassiz, Herbert Spencer, William Graham Sumner, Madison Grant, and Lothrop Stoddard; or by the proslavery intellectuals Katz mentions in the introduction—John C. Calhoun, Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright, George Fitzhugh, and Columbia professor John W. Burgess.

Was Bill Katz presciently peering into the future? No, he was looking back at the past, reflecting on his own experiences as a high school teacher in Westchester, New York, during the 1950s. He had graduated from Syracuse University during the early years of the Cold War and began teaching when the good citizens of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and related groups looked to ban “subversive” textbooks that discussed poverty, prejudice, the United Nations, and the writings of “liberal, racial, socialist, or labor agitators.”3 Having grown up in a world full of “liberal, racial, socialist, or labor agitators,” Bill was the sort of teacher the DAR despised. He recalls the FBI constantly tailing his father Bernard Katz, an agent boldly asking him: “Mr. Katz, if you say you are not a Communist why do you have so many books about Negroes?”Through his father, an organizer of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, Bill met a coterie of radical African Americans, including painters Charles White and Ernest Crichlow, performer and activist Harry Belafonte, and writer Alice Childress. Over the years, he would befriend pioneering historians and librarians such as Ernest Kaiser, Jean Blackwell Hutson, Dorothy Porter, Lerone Bennett Jr., John Hope Franklin, and John Henrik Clarke.

Not surprisingly, during the 1950s Bill encountered students who thought that slavery was a benign institution in which masters cared for joyful, contented, and blissfully ignorant Negroes. He recalled one kid reckoning, “If [the enslaved] didn’t like it, they would’ve revolted.” They had no clue of the long and rich history of Black resistance to slavery. “I began bootlegging material into the classroom,” he recalled, “often eyewitness accounts that revealed the role of Black people in American history. It strayed from the curriculum. It challenged textbooks and what they had learned before.”5 And it led to a lifetime of historical writing and editing, beginning with his first book,

Eyewitness: The Negro in American History (1967). Bill not only taught his students about the brutalities of slavery, dispossession, and Jim Crow, but understood that our knowledge of this history derives from anti-racist struggles. Anti-racist movements exposed America as a less-than-perfect union while charting a genuine path toward liberty for all. Once again, how is the history of anti-racism un-American? If we live in a country that is supposedly built on the principles of freedom and democracy, wouldn’t teaching about how courageous people risked their lives to ensure freedom for themselves and others be considered a good thing? Doesn’t it instill those values in students? Bill seems to think so: “I found my students, both Black and white, liked this content showing how enslaved people resisted and had some white allies [who] were moved by their conscience. These lessons showed the students how they could resist injustice and shape their own lives.”

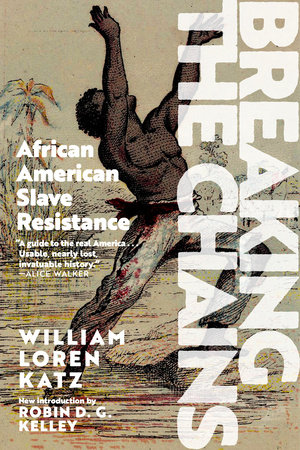

First published in 1990 by Atheneum,

Breaking the Chains distills nearly three decades of research on the history of slavery, resistance, and abolition. In 1968, Arno Press, a

New York Times imprint, hired Bill as the general editor of two series:

The American Negro: His History and Literature, which generated 141 volumes, and Anti-Slavery Crusade in America, yielding over 70 volumes. These were massive undertakings—the latter, in particular, still represents the most extraordinary collection of antislavery writings to date. In the interim, he had published several books, including

The Black West and Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage. Bill wrote Breaking the Chains for middle and high school students, but its breadth, scope, nuance, and subtle arguments made the book attractive to general adult readers. The opening chapters extend across the hemisphere, from the massive Brazilian quilombo of Palmares to slave rebellions in Mexico to the Haitian Revolution. Each story confirms Olaudah Equiano’s observation: “When you make men slaves, you . . . compel them to live with you in a state of war.”

Breaking the Chains challenges the claim that the 116-year conflict between France and England over succession to the French throne was the longest war in recorded history. Katz documents four centuries of continuous warfare and skirmishes between Europeans and Africans extending from the African continent, the high seas and coastlines of the Atlantic, and across the lengths of the Western hemisphere. Wars to procure captives transformed large swaths of West and Central Africa into battlegrounds, revealing in stark terms why the Atlantic system turned every nation into a garrison state.

The book captures the myriad ways Black people resisted enslavement. Of course, Katz narrates the better-known— and lesser-known—stories of revolts and conspiracies with eloquence and drama: Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser, the Stono Rebellion, and the Amistad Mutiny, to name a few. The Africans who managed to “break the chains” fled to free territory or found refuge in maroon communities with other fugitives as well as Indigenous nations. Marronage developed in hidden places (hills, swamps, mountains, wooded areas) and in plain sight (among Native nations such as the Seminoles in Florida). But one of the book’s greatest strengths is its recognition of resistance in the everyday acts of survival and the critical role of women in plotting and sustaining these acts. Katz demonstrates that in the realm of everyday life—in work, family, religion, culture—we find the bases for solidarity and political culture. Resistance to enslavement meant preserving dignity and sanity no matter what the costs. It meant fighting for education, literacy, knowledge; fighting to keep families and communities together and maintain physical and spiritual wholeness. Through worship and song, enslaved people sustained a culture of resistance. They embraced God’s word but rejected the master’s religion. The men and women who claimed ownership over other human beings were the real sinners, while Africans held in bondage were God’s children and the true believers. They tuned out the plantation preachers’ admonitions on slavery as God’s will, “theft” as sin, and the desire for liberty as the devil’s work. They transformed Christianity into a prophetic theology of liberation. The Bible consistently sided with the oppressed and the poor, and the God of the Old Testament had no qualms about employing redemptive violence to purge the land of sin. Indeed, this commitment to kith, kin, community, ancestors, God, and knowledge laid the basis for a Black post-emancipation vision of what freedom ought to look like and how society should be organized. This is exactly why people coming directly out of bondage led the way in creating the world’s first social democracy, however short-lived.

Finally, building on W. E. B. Du Bois’s magnificent Black Reconstruction in America, Bill Katz debunks the myth that Lincoln “freed the slaves.” If anything, the men and women who broke their own chains freed Lincoln of some of his most racist assumptions. Swirling in the middle of this conflict we call the Civil War was the largest slave revolt in the history of North America. At least one hundred eighty-six thousand armed Black men donning Union uniforms confronted their old masters on the battlefield, and over half a million fled the plantations and cities, causing the collapse of the Confederacy. The revolt birthed a new war to extend democracy and human freedom to all. Formerly enslaved people and antislavery militants tried to bring democracy to America. Men and women once held as property were determined to reconstruct the nation under new democratic principles, land redistribution, free universal education for all, and a new racial order based on equality and access to power. Tragically, they were defeated—twice. First, by the rise of Jim Crow; second, in Bill Katz’s words, by “new enemies wielding not guns but pens. These were scholars.” He was speaking of those historians who could not imagine Black people winning freedom for themselves and the nation by fighting for the abolition of slavery, racism, and all forms of oppression. The thought is downright un-American.

Breaking the Chains is still fresh, still relevant, and more dangerous than ever. It is a dangerous book not because it denigrates America or makes white children feel guilty and uncomfortable. Rather, it is dangerous because it shows us that the most oppressed and degraded people have the power, capacity, and moral vision to break their own chains and secure liberty, justice, and equality for all.

—Robin D. G. Kelley, Los Angeles, September 2022 AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTIONWilliam Loren Katz Heroic men and women crowd the pages of US history and punctuate its major events—defiant minutemen at Concord Bridge; brave pioneers plunging into the wilderness; intrepid Marines at Wake Island refusing to surrender; daring astronauts.

Africans who arrived here on ships full of enslaved people have not been part of this glorious heritage. When American courage is celebrated, enslaved people are left out. The story of their heroism has not often been told because history was recorded by those who sold, owned, or

profited from their labor.

To justify their profits from bondage, the men and women who trafficked in human lives invented useful tales. They insisted Africans were an inferior breed who benefited from the culture of their European and Christian owners. Vice President John C. Calhoun, a famous South Carolina

enslaver, said bondage made Africans “so civilized and so

improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually.” To excuse kidnapping Africans from their families and homeland, Virginia planter George Fitzhugh insisted enslaved people “love their master and his family and the attachment is reciprocated.”

Fitzhugh and Calhoun claimed Africans in slavery not only enjoyed hard work in the hot sun but were happier than any other laborers in the world. To justify keeping people in chains, enslavers bent history, truth, and the

Bible to their purposes. They also created their own “scientific evidence.” Dr. Samuel Cartwright of the University of Louisiana said Black people “consume less oxygen than the white” and this fact “thus makes it a mercy and a blessing to negroes to have persons in authority set over them, to

provide and take care of them.”

Central to the enslavers’ reasoning was the lie that Africans willingly accepted slavery and rejected rebellion. Dr. Cartwright claimed “there had never been an insurrection” against enslaver rule. When people in bondage tried to escape, the doctor called it “ Draptomania, or the Disease Causing Negroes to Run Away.” When Black people

rebelled, sabotaged production, and fought white enslavers

and overseers, it was “Dysthesia Aethiopica,” a mental disorder “peculiar to Africans.”

The lies of enslavers did not die quickly or easily. In 1863, after thousands of Black people had fled plantations to fight for liberty in the Civil War, Confederate president Jefferson Davis still called enslaved people “peaceful and contented laborers.” The Civil War ended slavery, but scholars and textbook writers carried on the planters’ view of the happy,

dull, docile slave. An ex-Confederate soldier, John W. Burgess, became a noted historian at Columbia University. He influenced generations of scholars with his views that African Americans were inferior to whites and content under slavery.

Thus, the enslavers’ version of the life of the enslaved had a lasting impact on historians from the North and South. Scholar William E. Woodward wrote that African Americans were the only people in history emancipated “without any effort of their own,” and two of this country’s most liberal and famous historians, Allan Nevins and Henry Steele Commager, wrote college texts that emphasized enslaved people were attached to their enslavers, “well cared for and apparently happy.”

The story of Dred Scott illustrates the way enslaved people were presented as pathetic stereotypes. Because of the Supreme Court case that bears his name, Scott has always been the one Black figure in US history courses. But little is said about him as a person—that he saw his first

wife and two children sold away, that he married Harriet, and they had two children, Eliza and Lizzie, whom he desperately wanted to live in freedom.

Historians wrote about a Dred Scott who was “lazy and shiftless.” Some even ridiculed him as a carefree, stupid man with no real interest in freedom. In American Heritage, famous Civil War historian Bruce Catton said Scott was “a man without energy” and attributed to Scott such words as his “case was ‘a heap o trouble,’” and “he was amazed at all ‘de fuss day made dar in Washington.’”

In fact, Scott shouldered huge burdens to lift slavery from his family. For a time he escaped to the Lucas Swamps outside St. Louis, a haven for enslaved people seeking freedom. Then he was recaptured and brought back. After that he mainly spent time working at extra jobs, raising cash to purchase his family’s liberty. When his enslaver, Mrs. Emerson, turned down the $300 he had saved, Scott hired a lawyer and brought his case before Judge Krum in St. Louis.

Despite rapidly deteriorating health and the onset of old age, Scott pursued this legal effort for ten years and ten months. Along the way he received some financial help from antislavery whites.

Though the Supreme Court ruled against the Scotts, a new enslaver soon freed them. The Scotts worked in St. Louis, Dred as a porter at Barnum’s Hotel and Harriet running a laundry business, with Dred helping her out after hours.

The real Scott story turns out to be one of courage and endurance by a family committed to liberty. But they never really had their day in court because they faced an all-white Supreme Court stacked against them. Then later scholars emphasized this distorted, stereotyped image.

Such fantasies about people held in bondage reached generations of teachers, textbook authors, and Hollywood writers. Their words and images penetrated millions of young US minds.

The seventh and eighth graders who entered my New York City classroom in the 1950s knew their slavery lessons cold. “Slaves didn’t really mind it,” said one, “because it wasn’t so bad.” “If they didn’t like it, they would’ve revolted,” said another. “Slavery was really like a kind of social security,” said a third. No one seemed to disagree with these views that they had been taught in elementary school.

To those reared on this version, it seemed un-American to depict the evils of slavery and disloyal to talk about African American people fighting for freedom against whites. Omitting, neglecting, or suppressing the facts of enslaved people’s defiance became a lasting American tradition.

The truth about bondage was always available. Before the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved men and women escaped and wrote more than a hundred autobiographies and published seventeen newspapers. Antislavery or abolitionist publications of the nineteenth century bulge with Black and white testimony exposing the evils of bondage. Six thousand pages of the recollections of formerly enslaved men and

women are on file at the Library of Congress, and hundreds of other interviews are kept at Fisk University. Most scholars have ignored this mountain of evidence. Some flatly said that while those who profited from slavery could be objective, those who suffered from it lacked powers of observation or sufficient detachment to judge fairly.

Enslaved people’s testimony reveals a heritage of rebelliousness stretching from the kidnappings in Africa to the end of the Civil War, and this American story adds a proud new dimension to the world struggle for freedom. Africans demonstrated endurance, resilience, and bravery in the face of the most wretched conditions in the Americas. They were among the first Americans to die for the great ideal that all are created free and equal.

Today the story of resistance to slavery can be described with a high degree of accuracy through accounts left by the men, women, and children held in bondage and their relatives and friends. I have chosen to construct this book largely based on their testimony, and I have also included the recollections of white enslavers and their families, foreign visitors, military and government reports, newspapers, and legal records.

Because this book is short and focuses on the Black contribution to emancipation, white participation, since it appears in many other books, is indicated but not fully examined. It was the resistance of the people in bondage that, each step of the way, galvanized whites and free Blacks

into action.

All quotations are by Black people, enslaved or free, unless otherwise identified. Some African American narrators, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman,have recently found their place in school courses. But other witnesses are largely unknown. Some left scant identification in the historical record except a few words, and a first or last name. Others left even less—a nickname, a state, a date. In telling their stories, some did not wish to give their name. More often the man or woman who took down their words did not bother to ask for one. I have included whatever information is known of these people whose surviving words bear witness to our common history.

—William Loren Katz

Copyright © 2024 by William Loren Katz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.