From the introduction: The Difficult Miracle This is the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America: that we persist, published or not, and loved or unloved: we persist. --June Jordan

For over 250 years, African Americans have written and recited and published poetry about beauty and injustice, music and muses, Africa and America, freedoms and foodways, Harlem and history, funk and opera, boredom and longing, jazz and joy. They wrote about what they saw around them and also what they dreamt up—even if it was a dream deferred, derailed, or outright denied. In sonnets and anthems, odes and epics, Black poets in the Americas confronted violence and indifference, legal barriers to reading and writing, illegal suppression of voting rights, and outright threats to their personhood, livelihood, and neighborhoods. They wrote from a world they made and a world that, at times, seemed designed to distract at best, to dis or destroy at worst. For African Americans, the very act of composing poetry proved a form of protest.

In this they were participating in a long line of creation, spanning back to the enslaved “Black and Unknown Bards” of the Negro spirituals, who transformed traditions and invented language to describe and change their conditions—and to take pleasure and power in their own inventiveness.

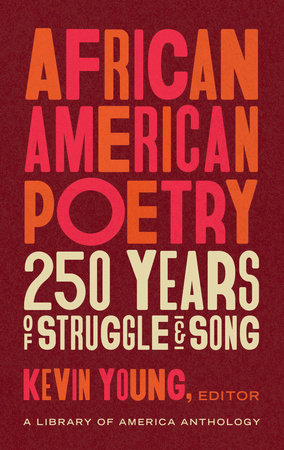

African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song captures a quarter-millennia of Black poetry in the Americas from Phillis Wheatley to the present day. Whether we consider that timespan to consist of what June Jordan calls “the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America,” what Amiri Baraka names “the changing same,” or the pleasure that Toi Derricotte invokes when she says “joy is an act of resistance,” this anthology provides a comprehensive look at the centuries of song and struggle that make up African American verse, a legacy that is fruitful and large enough to barely be contained in one volume.

Black poetry has always lived beyond books. If Wheatley was first to publish a volume—one she had to go to England to find support for—then the first poem of record by a person of African descent in North America is Lucy Terry’s “Bars Fight.” Composed orally in 1746, the poem was passed around for generations till first mentioned in print in 1819 and printed in full in 1855, the same year as Walt Whitman’s

Leaves of Grass. Poet Jupiter Hammon published several of his works, often pious, in newspapers and other outlets, starting in 1760; he was the first African American to published poetry in a magazine. But it wasn’t till Wheatley that an entire tradition coalesced, and fully began—with her poems addressed to British royalty and then-General Washington, contemplating creativity and creation and a freedom she ultimately would write herself into.

This book is organized in eight linked sections.

Section One: Bury Me in a Free Land (1770-1899) features a rich array of poets, from Wheatley to Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, all of whom encountered (and wrote against) bondage in some way.

Section Two: Lift Every Voice (1900-1918) considers poets from Paul Laurence Dunbar on, and the advent of the New Negro, including W.E.B. DuBois, novelist, poet, and anthologist James Weldon Johnson, poet and playwright Angelina Weld Grimké, and publisher and poet Fenton Johnson, whose prose poems inaugurate a modernist moment.

Section Three: The Dark Tower (1919-1936) focuses on the Harlem Renaissance and beyond, especially what James Weldon Johnson in his introduction to Sterling Brown’s

Southern Road in 1932 called the “Younger Group” of Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Hughes, Toomer, and Brown—a list notably missing any of the terrific women writers of the time, from Gwendolyn B. Bennett, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Anne Spencer, and the neglected by nearly all quarters Mae V. Cowdery, all robustly represented here. Indeed, this Dark Tower argues in its selections for women writers and LGBTQ voices sometimes ignored, and for a Renaissance that stretches from Paris to Philadelphia to D.C. to the American South and Caribbean.

Section Four: Ballads of Remembrance (1937-1959) takes us through the Chicago Renaissance of Gwendolyn Brooks and other poets of the wartime and postwar period, considering the period between the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. The results consider place across the land—from Alabama to Cleveland to New Orleans—and poets whose work too often falls by the wayside. This includes everyone from Beat poet Bob Kaufman to Margaret Walker, the first Black person to win the Yale Younger Poets Prize (and the only one for nearly 70 years afterwards).

The second half of the book charts the ongoing boom in Black poetry, starting with the Black Arts Movement featured in

Section Five: Ideas of Ancestry (1960-1975). This intense artistic and political outburst could fill, and has filled, many anthologies, but stands out for its foment in a short, intense period—from Amiri Baraka to Sonia Sanchez—much like the Harlem Renaissance before it. By expanding the period beyond the revolutions and unrest of the 1960s, we discover other poets who wrote alongside the movement, including Jay Wright and Michael S. Harper and Audre Lorde, who continued the work (and outlook) in the decades after, often shaped by Black Arts freedoms but also embracing a multitude of influences. The following

Section Six: Blue Light Sutras (1976-1989) continues with poets like Ai, who almost exclusively wrote persona poems, as well as Pulitzer Prize-winners Rita Dove and Yusef Komunyakaa, or Sherley Anne Williams and Christopher Gilbert—all of whom wrote in personal ways about history and its music. These artists came to see that recognizing a multitude of influences, and capturing an array of voices, meant something deeply Black too.

The book ends with what is arguably another, more current renaissance, an explosion of talent and culmination of tradition that began appearing in the early 1990s.

Sections Seven: Praisesongs for the Day (1990-2010) and

Eight: After the Hurricane (2011-2020) consider what appears now two generations of “furious flowering”—borrowing a phrase from Gwendolyn Brooks that became the name of the important festivals and poetry center formed by scholar JoAnne Gabbin in 1994. One is tempted to say that over these last two decades we are newly in a time of writing collectives, but this would be ignoring the presence, going back through time, of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People in the 1990s, the Umbra Group in the 1960s, the Black Opals or Saturday Evening Quills of the 1920s, or even groups like Les Cenelles in the nineteenth century. Yet, this tradition found a newfound form in the Dark Room Collective, whose emergence in the late 1980s after the funeral of James Baldwin helped galvanize the current moment and eventually included Natasha Trethewey and Tracy K. Smith, two Pulitzer Prize-winning poets who have also served as U.S. Poets Laureate. They have been joined, in just the Pulitzer alone, by Tyehimba Jess and Gregory Pardlo—representative of increased and overdue recognition African American excellence. As a kind of coda, this book’s final, eighth section can only hope to provide a representation and overview of our current moment and mood, whose vibrancy and varied voices follow in the footsteps of the hundreds of years (and pages) before. One selection per poet can merely hint at the new songs being written, the struggles always underway, and those yet to come.

Copyright © 2020 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.