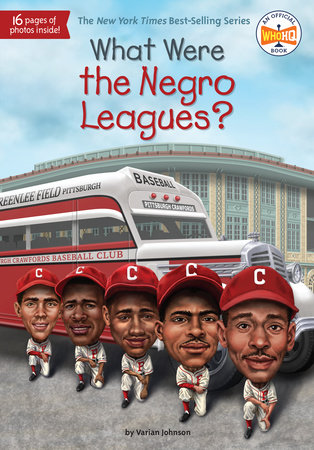

What Were the Negro Leagues? September 8, 1942: On a warm Tuesday, twenty thousand fans filed into the bleachers of Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC, to watch the first game in the World Series. The best-of-seven-game series was sure to be an exciting spectacle, with the top two teams competing against each other. The series featured some of the biggest baseball stars of the day—many of whom were later inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

But this game didn’t include big names, such as Joe DiMaggio or Ted Williams. Nor were Major League Baseball (MLB) teams, such as the Boston Red Sox or the New York Yankees, battling against each other.

That’s because this was the Negro League World Series. All of the players on both teams—the Homestead Grays and the Kansas City Monarchs—were black.

(Before the 1960s,

Negro was considered the polite way to refer to black people. Today, that is no longer the case.)

In 1942, not one major-league team had any African Americans on its roster. Why? White players refused to play with black teammates. So none were hired.

Black baseball players were just as good as or better than white players from the major leagues. The 1942 Negro League World Series featured seven future Hall of Famers, including Leroy Robert “Satchel” Paige. He was perhaps the best pitcher in Negro League history. Also, Josh Gibson. He was one of the most powerful hitters ever. Josh Gibson was so good at belting out home runs, many people called him “the Black Babe Ruth,” though fans who saw both players often called Ruth “the White Josh Gibson.”

The first few innings of the opening game of the 1942 Negro World Series were close. Neither team was able to score. But in the fourth inning, two Homestead Gray players finally made it on base. Then came Gibson, six feet one and weighing over two hundred pounds. Satchel Paige stood across from him at the pitcher’s mound.

The best against the best.

Paige wound up and pitched the ball. It went flying across the infield. Gibson swung, and with a crack, the bat connected. The ball flew far and high . . . but not far enough and not high enough. The ball was caught at center field.

Gibson was out.

There would be no home runs for Gibson or the Homestead Grays that day. The Kansas City Monarchs won the first game 8–0.

In the second game, Paige and Gibson faced each other again. Some said that Satchel Paige deliberately walked two players, loading the bases, just so he could pitch against Josh Gibson. Former Monarchs player and manager John “Buck” O’Neil even claimed Paige taunted Gibson before striking the slugger out with a “one-hundred-and-five-mile [an-hour] fastball.”

Although Paige probably didn’t walk two players on purpose, the series became a classic. Thanks to Paige, Gibson, and others, over sixty thousand fans attended the World Series!

None of the players could know that Negro League baseball was almost at its peak. Big changes would soon come to baseball. And even though these changes led to the end of the Negro Leagues, its legacy would continue to live on and inspire today’s fans.

Chapter 1:

The Beginning of Baseball Standardized baseball in America began in 1845. That’s when the first written rules were created for the New York Knickerbockers baseball team. Before this, many ballplayers played other “bat and ball” games, like cricket, a game from England. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, thousands of people were playing baseball all across the country. The war even increased the sport’s popularity. Whenever soldiers got the chance, they would play baseball for fun and teach one another about the game.

As more and more people became baseball fans and watched local games, some teams decided to turn professional. In 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first baseball club to pay its team members for playing. The Red Stockings traveled around the country, sometimes bringing in crowds of twenty thousand people.

As news of the Red Stockings’ success spread, more teams began to turn professional. In time, these teams began to work together to form

organized leagues, with standard pay for their players and set schedules for their teams. Eventually, the two main baseball leagues—the National League and the American League—came to be known as Major League Baseball, or the majors.

The end of the Civil War led to the end of slavery. Black people began to play popular sports, like baseball, that before had been reserved for whites. But many white people believed that the two races should stay separated from each other. (This is called segregation.) They shouldn’t be playing baseball with each other. But maybe there was also another reason. Perhaps white players did not want to be embarrassed by being struck out by a black pitcher or having a black player score a home run on them.

Although many baseball clubs were racist, some black players did make it onto white baseball teams. One was John “Bud” Fowler. Born in 1858 in New York, Fowler became a professional baseball player in 1878.

Fowler was a skilled catcher, first baseman, and pitcher, but his best field position was second base. He was also great at hitting the ball, batting over .300 every season. (That means he reached base at least three times out of every ten times at bat.) Fowler was even a baseball innovator. Because so many white players were intentionally striking his legs with their spiked shoes, Fowler began wearing wooden slats over his shins so he could protect himself—creating the first baseball shin guards!

But as good as Fowler was on the field, no baseball teams kept him on their roster for very long. As soon as a good white player came along who played the same position as Fowler, he would be fired. By the time he stopped playing baseball, Fowler had suited up for more than fourteen different teams in nine different leagues over ten years.

Another important black player in pro baseball’s early days was a man named Moses Walker. In 1884, Walker joined the all-white Toledo Blue Stockings—the first black man to play on a major-league team.

Walker was a catcher. Part of his job was to tell the pitcher what type of ball to throw to each player. But one of the pitchers on his team refused to take orders from a black player. No matter how many hand signals Walker would give, the pitcher always ignored him.

As other black players tried to join white baseball clubs, professional baseball leagues all across the country worked together to stop this from happening. There was an unwritten agreement: No black players would be hired. And indeed, none were. By 1899, black players were totally shut out of professional baseball.

But these black players did not give up. As famed civil rights activist Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois said, “If Negroes were to survive and prosper in White America they would have to do for themselves what whites were unwilling to do.” These black players decided that if they couldn’t play on white teams, then they would create their own.

Chapter 2:

The First Black Pro Teams In 1885, Frank P. Thompson was a headwaiter at the Argyle Hotel, a resort on Long Island, New York. According to black baseball player and historian Sol White, Thompson noticed that a number of the waiters at the hotel played baseball in their free time. Thompson hired these men and others to form the first professional black baseball team. They were called the Cuban Giants.

Why did they call themselves “Cubans”?

According to Sol White, who actually played for the Giants in 1891, it was to hide the fact of being black. (They also supposedly spoke a made-up language on the field that sounded like Spanish.) It’s possible that the team thought they would face less racism by pretending to be Hispanic.

In time, the name “Giants” began to serve as a code word to let African American baseball fans know that a team was made up of black players. Other black teams started to pop up across the United States, with names like the Elite Giants, the Leland Giants, and the Mohawk Giants.

As good as these teams were, their fan base wasn’t nearly as big as that of the white professional teams. The teams could not make enough money from the number of tickets bought by local fans. So they had to go on the road. Teams like the Cuban Giants often had to travel long distances for weeks or months to find teams to play against and new fans who would pay to watch the games.

Barnstorming, as it was called, became the way of life for black baseball players. The teams would load up all their players and equipment in buses or cars and travel from town to town, looking for other baseball clubs to play. To make as much money as possible, they often scheduled two or three games in a single day (doubleheaders and triple-headers). The Homestead Grays were reported to travel thirty thousand miles during a 179-game season. In the cold winter months, many teams traveled to the Caribbean and Central or South America so they could continue playing.

Barnstorming was hardest when black ball teams traveled through the southern United States.

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court upheld a law. It said that segregation was legal. This meant that black children had to attend all-black schools. Black families couldn’t eat at the same restaurants or spend the night at the same hotels as white people. They couldn’t even use the same bathrooms as white people or drink from the same water fountains—and the restrooms for black people were never as nice. Many times, black players had to sleep in people’s homes if there wasn’t a hotel for black people in town. Other times, they would sleep on the ground next to the baseball field.

Even so, black baseball players loved the game so much that they kept on going. They played anywhere, against anyone, anytime!

Copyright © 2019 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.