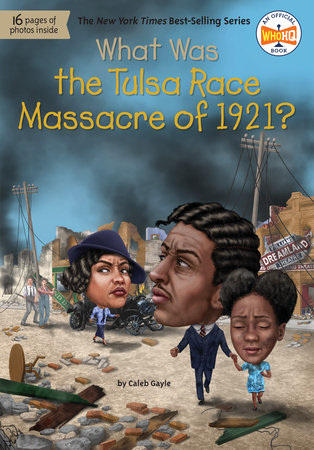

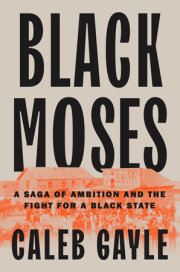

What Was the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921?

May 31, 1921

Tuesday was prom night for the students of Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Like other proms held in past years, kids would show up in suits and ties, dresses, and their best shoes. They would dance the foxtrot and the cakewalk to the popular music of the 1920s—jazz, ragtime, and barrelhouse.

Veneice Sims and Verby Ellison were going to the prom together. Veneice’s parents were allowing her to stay out until midnight—a special treat. Veneice, much later in her life, remembered how she was looking forward to cutting loose on this fun night.

Usually, her dad would only let her play church music on the family’s Victrola record player. At the prom, she planned to dance, dance, dance. Beforehand, she laid out her blue silk dress, silver shoes, and a pearl necklace borrowed for the night. She was living her best life. And why wouldn’t she be?

Her dad was a mechanic for the bus company. She lived in a three-bedroom home in a nice neighborhood. She had enough money to have the kind of prom dress and shoes most girls dream of. Not to mention, the Sims family had a car.

By 1921, Veneice’s parents had achieved the “American Dream” of success. This was especially remarkable because the Sims were Black. Not many other Black families (or white families) in America lived nearly as good a life as the Sims did. Even in the booming 1920s, nearly 60 percent of Americans were living in poverty, most ofthem Black people, immigrants, and farmers.

Named after the famous Black political leader, educator, and author, Booker T. Washington was an all-Black high school in the all-Black neighborhood where Veneice lived. It was called Greenwood, but to many it was better known as Black Wall Street.

Black Wall Street covered thirty-five blocks. It got its nickname because of the many thriving businesses there. (Wall Street in New York City is a famous financial center.) Almost two hundred stores populated the area: hotels, restaurants, barbershops, two theaters, tailor shops, schools, a skating rink, and more. There was a public library, a hospital, a bus company, grocery stores, and about twelve churches. Many of the businesses were owned and operated by Black people. This was unusual back then. People who came to visit were impressed. It seemed like this part of the country—the southwestern United States, where Oklahoma is—offered the best chance for Black people to make a good life for themselves.

There were, however, dangers to living in a neighborhood like Greenwood.

Black Wall Street and the white neighborhoods of Tulsa were separated. Some white people resented that this nearby Black community was doing so well. This made things very dangerous for Greenwood’s Black people.

On prom night, before Veneice Sims got to slip into her beautiful blue dress, violence erupted in her neighborhood. White rioters began a brutal attack against the Black people in town. She heard men shouting, guns firing. All of a sudden, her dad was shouting to her, “There’s a race riot. It’s time to go.”

Only twenty-four hours later, little of Black Wall Street was left standing. A massacre is when lots of innocent people are murdered, and their property destroyed. That’s what happened in Greenwood. That’s why this terrible event is known as the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. It was one of the worst instances of racial violence in US history.

Chapter 1: The Promise of Oklahoma In the late nineteenth century, some parts of Tulsa, as well as other places now part of the state of Oklahoma, were becoming known as safe havens for Black families. Places where they could make new and better lives.

For decades, there had been Black people living in Oklahoma. They first came as enslaved people, but also as never-enslaved Black Native people of five tribal nations of Native Americans—the Chickasaw, Seminole, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek. These tribal nations had been living in the southeastern United States but were forced from their native lands by President Andrew Jackson.

One hundred thousand Native Americans had to move west, to what was called “Indian Territory.” Some Native Americans brought with them enslaved Black people who were freed after the Civil War ended. Many remained in Oklahoma. Their children and their children’s children often started their own towns. Between the end of the Civil War and 1920, more than fifty Black townships had sprung up. (Thirteen of these towns remain today.)

From 1865 to 1877, the United States government carried out programs to help roughly four million newly freed people in the South, as well as in Indian Territory. This period of history is known as Reconstruction. But attempts to make life better for Black people were seen by many white people as unfair. White politicians and voters soon passed laws to make life as hard as possible for Black people. For example, certain laws made it essentially impossible for Black people in the South to vote or get good jobs.

Because of this, many Black people in the 1880s, 1890s, and early 1900s decided to leave the South behind. Many ended up relocating to Oklahoma and Kansas. In 1906, a wealthy Black landowner named O. W. Gurley bought forty acres of land in Tulsa and named the area Greenwood. He sold some of this land to other Black people, who built homes and businesses.

Oil was discovered in Oklahoma in the late 1890s. Oil still impacts our lives today. It fuels our cars, heats our homes, and even creates the asphalt for paving our roads. Soon, Tulsa became known as the “Oil Capital of the World.” People came to work in the oil fields. Those people also needed barbershops, grocery stores, restaurants, and more. Because of oil, the city of Tulsa grew rapidly. The city’s population rose from 18,000 in 1910 to 140,000 by 1930.

Not only did Tulsa keep growing but Black Wall Street did, too. Black people created their own neighborhood because they were not allowed to own houses in white areas; they couldn’t start their own businesses there. If their jobs were in white neighborhoods, they had to use bathrooms with signs that said, “For Coloreds.”

By 1921, residents of Greenwood could watch a play at the Dixie Theatre or a movie at the Williams Dreamland Theatre. They could go for sandwiches at Little Pullman Cafe or treat themselves to waffles at the local waffle house. The Stradford Hotel had fifty-four rooms and was considered one of the finest Black hotels in the country. On street after street, Black people were shopping at mainly Black-owned businesses. Down one street was Loula Williams’s confectionery. (A confectionery is a store that sells candy and ice cream.) Down another was Rebecca Brown Crutcher’s barbecue pit. It welcomed home men working in the oil fields just miles out of the city. Within Greenwood, not every person was growing rich. But many were.

This sense of opportunity, within a mostly segregated country, appealed to many Black people long after the Exodusters had set their sights westward.

Just outside of Tulsa, another small Black community called Red Bird published brochures to get more people to come. The brochures described the great wonders of Black life in the small town. One read, “A Message to the Colored Man . . . Do you want a home in the Great Southwest—The Beautiful Indian Territory? In a town populated by intelligent, self-reliant colored people?” In the brochure, a minister named Jason Mayer Conner wrote of his own experience, “I have made a personal visit to the Indian Territory and know it to be the best place on earth for the negro.” Others said that “this country is the Paradise for the colored man.” The words

Negro and

colored were commonly used in the 1900s, but they are considered offensive today.

Newspapers like the Black-owned

Muskogee Comet reported that this part of Oklahoma “may verily be called the Eden of the West for the colored people.” A newspaper in Kansas called the

Afro-American Advocate pleaded with Black people far and wide to “come home, come home . . . Come out of the wilderness from among these lawless lynchers and breathe the free air.”

In Greenwood, stories about people like Mabel Little proved that these claims were true. Mabel’s grandparents had been enslaved. She came to Tulsa with not much at all. It was rough at first—she could barely afford to rent a room in a boardinghouse. But Mabel got a job working at a hotel. Soon after, she met a man named Pressley, who shined shoes. They got married and saved up enough money to buy a small three-room house. Pressley ran his shoe-shining business in one room of the house. Mabel opened her own beauty shop in another. It had a staff of three and was later featured in the famous Black magazine

Ebony. The couple bought a Ford Model T car.

By the time of the massacre, Mabel and her husband had made it: They had built a five-bedroom home. Her husband opened his own restaurant, and the couple rented out two other houses that they owned. Stories like these were not uncommon in Greenwood. But they all came to a bitter and sad end.

Copyright © 2023 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.