One

“Worse Than 100 Boys”

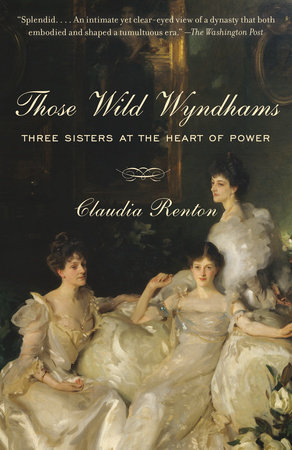

The eldest daughter of the portrait, Mary Constance Wyndham, was born to Percy and Madeline in London in summer’s dog days on 3 August 1862 and privileged from birth. Percy, called “the Hon’ble P” by his friends, was the favored younger son of the vastly wealthy Lord Leconfield of Petworth House in Sussex, a county some fifty miles southwest of London. Percy’s occupation was holding down a family parliamentary seat in the north of England as the Conservative Member for West Cumberland. He had a kind heart and the family traits of an uncontrollable temper and an inability to dissemble. It was true of him, as was said of his father, that he had “no power of disguising his feelings, if he liked one person more than another it was simply written on his Countenance.”

Percy’s Irish wife, Madeline, was different. Known in infancy as “the Sunny Baby,” she was renowned for her expansive warmth. “She is an Angel . . . She has the master-key of life—love—which unlocks everything for her and makes one feel her immortal,” said Georgiana Burne-Jones, who, like her husband, Edward, was among Madeline’s closest friends. Yet in courtship Percy had spoken much of Madeline’s reserve—“you sweet mystery,” he called her, one of very few to recognize that her personality seemed to be shut up in different boxes, to some of which only she held the key. Madeline, rumored to be descended from French royalty, had a romantic, disreputable ancestry: breeding, but no money. She and Percy had married for love. The substantial dowry Madeline had brought to the marriage was provided for her by her doting father-in-law, Lord Leconfield.

At the time of Mary’s birth, Percy and Madeline were twenty-seven years old, two years married, and lived an elegant, leisured life befitting the son and daughter-in-law of one of England’s richest men. They divided their time between stately Petworth, Cockermouth Castle—a grandly named but ramshackle family property in Percy’s constituency given to them by his father for their use—and fashionable Belgrave Square, at no. 44, where Mary was born. Madeline’s mother, Pamela, Lady Campbell, came over from Ireland for the birth, and during Madeline’s labor sat anxiously with Percy in a little room off her daughter’s bedroom. The labor was short—barely four and a half hours—and difficult. Lady Campbell had threatened to call her own daughter “Rhinocera” when she was born because of her incredible size. Mary, at birth, weighed an eyewatering eleven pounds. “The size and hardness of the baby’s head (for which I am afraid I am to blame),” Percy told his sister Fanny with apologetic pride, had required the use of forceps to bring the child into the world. “Of course we should have liked a boy but I am very grateful to God that matters have gone so well,” Percy concluded.

Percy and Madeline’s daughter held within her person the blood of Ireland and England—a physical embodiment of the vexed union between the kingdoms. Ireland was not, officially, a colony: it had shared a crown with England since King Henry VIII’s time. Yet since 1800, when its Parliament was abolished and its MPs sent, outnumbered, to England’s Westminster Parliament (a result of the abortive 1798 Irish Rebellion, in which Madeline’s grandfather Lord Edward Fitzgerald had died a nationalist hero and martyr), Ireland had been little more than an English satellite. In 1844 Parliament debated the motion “Ireland is occupied, not governed.” Benjamin Disraeli, writer and ambitious fledgling MP, described “a starving population, an absentee aristocracy . . . an alien church, and . . . the weakest executive in the world.” The novelist was exercising some artistic license—by 1873 only 20 percent of Ireland’s aristocracy were technically absentee—but fundamentally his depiction was and remained true. By the time Mary was a child, the republican Fenian Brotherhood was conducting a terrorist campaign in London. Instinctively iconoclastic, raised on stories of her rebellious great-grandfather and his French Catholic wife (known as “la Belle Pamela” for her beauty, and widely recognized as the illegitimate daughter of the royal revolutionary Duc d’Orléans and his fiercely intelligent mistress Madame de Genlis, a disciple of Rousseau’s), Mary’s childhood sympathies were with the oppressed and not the oppressors. She and her younger brother George—so she said later—were “the Fenians of the family.”

The harum-scarum hoyden was—like the age that bred her—hopeful, endlessly curious, entranced by novelty and change. At the time of Mary’s birth, Britain’s explorers were expanding the boundaries of the known world, their imperialists extending Britain’s governance over it. In Africa, Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke discovered the Nile’s source. The British Crown was declared official ruler of India by parliamentary Act, wresting control from the East India Trading Company, which had hitherto governed the continent. The British were a “race girdling the earth,” trumpeted the radical, imperialist politician Charles Dilke in his best-selling Greater Britain. The British mission was civilizing and Christian. Yet the mid-Victorian era’s unquestioning faith had been seriously shaken by Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published in 1859. Evolutionary theory challenged everything an evangelical nation had been taught to believe. Mary, who as a child had fossils shown and explained to her by her father, was born into a world ebullient in its capacity for exploration and invention but, in post-Darwinian terms, questing and unsure.

As Mary progressed from infancy to childhood, the landscape of modern London formed about her: Joseph Bazalgette built the great river walks along the Thames known as the Victoria and Albert Embankments (their purpose: to cover the new sewage system that meant the Thames was no longer the city’s chamber pot). The telephone and the first traffic light (short lived, it was installed outside the Houses of Parliament in 1868, only to explode in 1869, gravely wounding the policeman operating it) were inventions of her early youth. Inside that Parliament, however, little had changed. The presence of a band of “Radical” politicians seeking social change did not diminish the fact that the patriarchy was dominant. Stringent property qualifications meant that in the early 1860s, only one in five males could vote. The 1867 Reform Act, which extended the franchise to the wealthiest of the urban male working classes, was known popularly as “the Leap in the Dark.” In fact it was fundamentally limited: but the nickname demonstrates how the political elite feared democracy as a gateway to mob rule. Women could not vote at all. Upper-class women could not even appear in public without a chaperone.

Mary was the child of a love match—on one side, at least. It had been a coup de foudre for shy, crotchety Percy when he met dark, voluptuous Madeline Campbell in Ireland as 1860 dawned. Madeline was sensuous, earthy, physical. “People in her presence feel like trees or birds at their best, singing or flourishing according to their own natures with an easy exuberance . . . she has a peculiar gift for making this world glorious to all who meet her in it,” said her son George, who never shied away from the Oedipal undertones of his relationship with his mother.

Percy and Madeline were engaged in London in July, and married in Ireland in October. During a brief interim period of separation, as Madeline returned to Ireland, Percy gave voice to his infatuation in sheaves of letters, still breathtaking in their intensity, that daily swooped across the Irish Sea. “[D]ear Glory of my Life sweet darling, dear Cobra, dear gull with the changing eyes, most precious, rare rich Madeline sweet Madge of the soft cheeks,” said Percy, pouring forth his love, longing and dreams for the future. With barely concealed lust he begged Madeline to describe her bedroom so he could imagine her preparing her “dear body” for bed, and recalled, with attempted lasciviousness charming in its naivety, their brief moments of physical contact—a kiss stolen on a balcony at a ball; a moment knocked against each other in a bumpy carriage ride. “[I]f these letters don’t make you know how I love you, let there be no more pens, ink and paper in the world.”

No corresponding letters from Madeline survive. Brief fragments of reported speech suggest she was more world-weary than her besotted swain. “Oh Percy, Percy, I don’t think you know very much about me, but that’s no matter,” she told him. Some of her descendants think that there may have been a failed love affair in her past; if so, she successfully, and characteristically, erased all trace of it. Her reserve only strengthened Percy’s attraction.

Madeline’s soldier father, Sir Guy Campbell (who had a baronetcy, but no fortune), had died when she was just thirteen, leaving his widow to bring up twelve children on an army pension. Madeline would receive just fifty pounds a year on her mother’s death. The infatuated Percy persuaded his forbidding father—who succumbed immediately to Madeline’s charm on meeting her—to dower his bride. A month before the Wyndhams married, £35,727 16s. 5d. in government bonds (equivalent to around $4 million today) was transferred from Lord Leconfield’s Bank of England account to the trustees of Percy and Madeline’s marriage settlement. The trust was to provide for Madeline and any younger children of her marriage. From the capital’s interest Madeline would receive annually a personal allowance, known as pin money, of around £300. A provision stipulated that if the marriage proved childless, the money would devolve back to the Leconfields. Otherwise there was no indication that Madeline had not brought this money herself to the marriage. A baronet’s genteelly impoverished seventh daughter had been effectively transformed into an heiress of the first water.

The provision was never exercised. Percy and Madeline had five adored children over the course of a decade—the three girls, and the boys George and Guy. “Ever since your birth has my Heart & Soul loved you & laughed with you & wept with you . . . [illegible] to you, to dance, & sang to you to sleep—& anguished with you in all your sorrows . . .” wrote Madeline Wyndham to her youngest, Pamela. She might have made the comment to any of her children, all of whom Percy deemed “confidential,” his highest form of praise. Madeline Wyndham had been raised in a Rousseauesque environment in which she and her sisters (with no governess—doubtless partly for financial reasons) were encouraged to educate themselves, reading whatever they chose, and exploring the natural world in the fields around Woodview, their rambling house in Stillorgan, then a small village outside Dublin. Percy, raised in frigid splendor by evangelical parents who banned everything from novels to waltzing, was entranced upon first visiting Stillorgan. He vowed that his children would be raised in a similarly warm, loving and natural milieu. It has been said by George’s biographer that, despite an aristocratic lifestyle, the loving intensity of life among the Wyndhams was almost bourgeois.

That lifestyle was indisputably aristocractic. An audience of staff overlooked their every move: butler, housekeeper, footmen, housemaids, cook, kitchen maids, stable boys, gardeners and the “odd-man” who lit the house’s lamps each evening as dusk fell. The family rarely went anywhere without its retinue: Madeline Wyndham’s lady’s maid Easton (known as “Eassy”), Percy’s Irish valet Thompson (“Tommy”), the children’s nanny (the magnificently named Horsenail), nursemaid Emma Drake and, when the children were a little older, governesses and tutors. The Wyndhams belonged, impeccably, to “Society”—a close-knit, interconnected group, known sometimes as “the upper 10,000”: being the four hundred or so families that constituted Britain’s ruling class.

To outsiders Society seemed an impenetrable, corporate mass with “a common freemasonry of blood, a common education, common pursuits, common ideas, a common dialect, a common religion, and—what more than anything else binds men together—a common prestige . . . growled at occasionally, but on the whole conceded, and even, it must be owned, secretly liked by the country at large,” said the Radical Bernard Cracroft in 1867. Yet by the 1860s a sea change was taking place. Following the death of her beloved Prince Albert (aged just forty-one) in 1861, Queen Victoria retreated into deepest mourning for near on a decade. The monarchy’s public face—by default—became Victoria’s son Bertie, Prince of Wales, the polar opposite of his high-minded father. Sybaritic Bertie’s fast-living, hard-gambling Marlborough House Set was soon caught up in a number of scandals. Percy and Madeline knew the Prince and his wife, Alix, often attending the same social events. But Bertie and his friends considered Percy and Madeline’s set markedly bohemian since, in the words of the novelist and designer Alice Comyns Carr, they “took a certain pride in being the first members of Society to bring the people of their own set into friendly contact with the distinguished folk of art and literature.”

Madeline and her aristocratic friends dressed in flowing gowns, tied their hair back simply and draped themselves in scarves and bangles. Madeline was reputedly the first woman in England to smoke, with a habit of three Turkish cigarettes a day, one after each meal. They were disciples of the Pre-Raphaelites: their bibles were Malory’s Morte d’Arthur and Tennyson’s poem of the same title. Against the backdrop of their own family seats—Scottish castles and English stately homes—they posed in medieval dress for Julia Margaret Cameron’s camera. Madeline’s friend Georgie Sumner even dyed her hair red to resemble more closely “stunners” like Lizzie Siddal, muse and wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In London’s Kensington, where an artistic colony was blooming, they frequented Little Holland House, home of Cameron’s sister, Sara Prinsep, where G. F. Watts was literally the artist in residence (he moved in during a period of illness, and never left); and Leighton House, the creation of Frederic Leighton, later President of the Royal Academy. They considered Burne-Jones, then not yet famous, a genius. Madeline herself was a talented amateur artist, with a near-perfect eye and a skill for decorative arts. In 1872 she helped to found the School of Art Needlework with her friend Princess Christian, one of the Queen’s many daughters. In later life, she studied enameling under that craft’s master, Alexander Fisher. Madeline’s artist friends thought she had a true artist’s soul. Beauty could cause her “thoughts that fill my heart to bursting,” she told Watts: the beauty that, for the Pre-Raphaelites and their heirs was a necessity: a civilizing force and civic responsibility intended to arrest the physical and spiritual ugliness of an industrial age, of the factories and urban slums sprawling across much of England.

Cumberland (now renamed, and part of Cumbria), in the northwest of England on the Scottish border, had escaped the industrialization that had blighted the landscape of the Midlands. Remote, wild, mountainous and unspoiled, even after the Cockermouth to Penrith railway line opened in 1865 it was still a full day’s train journey from the capital—some ten to eleven hours. Life in Cumberland, land of the Lake District, of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was strangely removed from the Wyndhams’ normal existence. As if in a Pre-Raphaelite painting brought to life, Madeline Wyndham took her children out among the heather to draw and paint, and read aloud to them Arthurian tales.

Copyright © 2018 by Claudia Renton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.