Chapter One

The Bargain-Basement Economy

By the time I arrived at Atrium Medical Center, the relatively new hospital just outside my hometown of Middletown, Ohio, my dad’s care was focused on keeping him as comfortable as possible as his body slowly gave out. He wound up in the hospital after falling down the stairs, which resulted in a punctured lung and broken ribs. Lungs are pretty amazing, and if somewhat healthy will actually close holes and heal on their own. But because his lungs were far too damaged owing to asbestos exposure in the factory, along with a pack-a-day cigarette habit that started in his teens, they were stubbornly refusing to heal. And he was much too weak to be a candidate for surgery.

My dad’s chances of surviving after that unlucky tumble were determined by the story of his entire working life. Like many men of his time, he graduated from high school and went right to work at Armco Steel (now AK Steel, since being bought by Kawasaki in the 1990s). He started at the bottom, on rotation and on call for any number of dirty, backbreaking jobs in the coke plant. After about a decade, he enrolled in the company’s apprenticeship program to become a machinist. After twenty-nine years of service, he retired with a nice pension and a gold tabletop clock. But his body paid the price. While he was “only” seventy-three years old, his body was well worn, especially his lungs, which instead of being plump like pink cotton candy were pockmarked, strained, and a lifeless gray. As he lay in a morphine-induced state of bare consciousness, our family gathered in this sparkling new medical facility, which my hometown was depending on to revive itself in the post-manufacturing world. Just a mile or so down the two-lane highway on which the ten-building medical campus sits are brand-new upscale developments, complete with stainless-steel appliances, granite counters, and sunken bathtubs. In 2015, AK Steel announced plans to build a new $36 million research and innovation center in Middletown, a major recommitment to the town, and one that would have made my dad proud. The area’s proximity to Interstate 75, which connects Middletown to Cincinnati to the south and Dayton to the north, makes it appealing for bedroom communities and office developments.

But none of this was on my mind as I sat in my dad’s room all day interacting with a cadre of health-care professionals, each of whom was responsible for one aspect of my dad’s care. What did manage to break through the haze was the seemingly endless number of health-care workers who played some role in caring for my dad.

There was the young man in scrubs who was the attending physician’s assistant and who, unremarkably, was thought to be the doctor until he responded to a medical question by saying, “That’s a question for the doctor—I’m just her assistant.” There was the respiratory therapist, who was gentle and efficient. There was the nursing assistant who skillfully turned Dad to change his bandages, her body seemingly too small for the task at hand. Then there were the four young men who gingerly yet powerfully managed to move my dad and all the machines tethered to his body into a new bed. And finally there was the nurse who was on duty during what would be Dad’s final hours with us. He was young—maybe late twenties—and wonderfully gifted at his job. I remember wondering how many of these young men and women would probably have worked on the factory floor a generation ago. Today health-service occupations are one of the biggest providers of jobs in the economy. And like the small army that cared for my dad, the wages range from poverty-level to solidly middle-class.

The need for legions of health-care workers, still mostly women but with a modest and growing percentage of men, will continue to swell as the baby boomers grow old and frail. In fact, it will be the low-paid health-service jobs that will increase the most as more baby boomers retire. This bargain-basement economy will grow the most for the foreseeable future—not the much-touted knowledge economy. Topping the list of occupations that will add the most jobs to our economy are retail salespeople, child-care workers, food preparers and cooks, janitors, bookkeepers, maids, and truck drivers. Of the thirty occupations that will add the most jobs in the coming decade, half pay less than $30,000 a year.

This is the heart of America’s working class today. And it will be even more so tomorrow.

Like the hard-hat working-class jobs of previous generations, today’s working-class jobs are physically demanding, in somewhat surprising ways. Take, for example, this common job description for home health aides: “Appreciable physical effort or strain. Moderately heavy activity. May include lifting, constant stooping, and walking.” Four decades ago, backbreaking work on the factory floor offered hourly wages in the high teens. Being a home health aide, a common example of a manual labor job, entails lifting and moving people, not slabs of ore, and pays an average of $20,000 a year. At its heyday back in 1970, manufacturing accounted for 30 percent of all jobs, making the United States truly a blue-collar nation. No industry today comes close to the sheer dominance manufacturing had in our economy. But taken together, education and health services, along with leisure and hospitality—two big industries where bargain-basement jobs dominate—match the former heft of manufacturing. That’s basically what’s behind the transformation of working-class jobs in America. As companies shuttered factories in the United States and income inequality began its steady ascent, jobs for home health aides, child-care workers, fast-food workers, janitors, and waiters swelled to accommodate major cultural and social trends, including the growing disposable income of the upper echelon and the time crunch facing all workers, but especially those who have young children or aging parents to care for.

The New Big Jobs: Feeding, Serving, Caring, and Stocking America

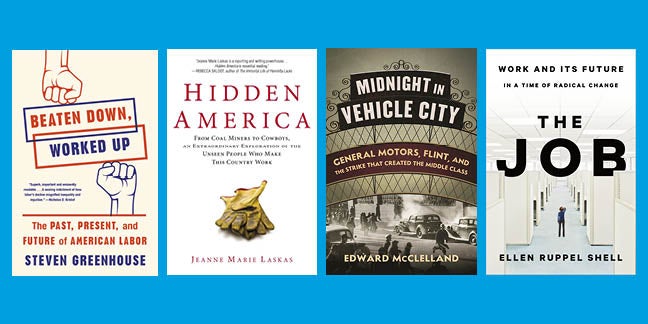

The old leviathan of the blue-collar working class, the auto industry, is commonly referred to as the Big Three, meaning GM, Ford, and Chrysler. In their prime, these companies symbolized American ingenuity, prosperity, and industrial hegemony. Despite major setbacks, including bankruptcy filings, the Big Three automakers have rebounded, though employing a fraction of the workers they did at their peak. And in an unprecedented concession, the United Auto Workers (UAW) union agreed in 2007 to a two-tier wage system, with new workers hired at lower wages and with fewer benefits. Today about 134,000 hourly workers are employed by the Big Three, and a full quarter of those workers earn second-tier wages—$15.79 to $19.28 an hour, compared to the first-tier wage of $28. In 2015, the UAW successfully renegotiated contracts with the Big Three automakers, bringing entry-level wages into line with veteran wages. For example, Fiat Chrysler workers approved a new contract that would bump entry-level workers’ pay up to $28 an hour after eight years and provide signing bonuses for new hires. Workers at GM and Ford won similar new wage terms. To the tens of millions of individuals working in today’s bargain-basement economy taking food orders, bathing the elderly, mopping floors, and stocking warehouses, even the auto workers’ second-tier wages would represent a fat raise. One of the reasons even second-tier wages at the Big Three are higher than the average wages in the jobs that form the backbone of the working class today is that those autoworkers still have a union. The same is no longer true for broad swaths of workers toiling in what has become the largest source of jobs in the auto industry, auto parts manufacturing. Today nearly three-quarters of auto jobs are in parts manufacturing, and increasingly those jobs are being filled by temporary staffing agencies. One estimate found that approximately 14 percent of auto-parts workers were hired through a staffing agency, with paychecks 20 percent lower than those of workers who were hired directly.

The degradation of manufacturing jobs, even when they’re brought back to the United States, reveals just how challenging it is for today’s workers to fight for a decent living. The fact that the once mighty, union-dense manufacturing sector can devolve into a place of low-paid, temporary staffing gigs is indicative of the power that’s been lost by our once working-class heroes. And it underscores the obstacles to rebuilding livelihoods for the majority of American workers.

The largest sources of jobs for the new working class fall into four main groups: retail and food jobs, blue-collar jobs, cubicle jobs, and caring jobs (see Table 1). Many of these jobs exist at the bottom of a long line of contracts and subcontracts, or are staffed by temp agencies, or are part of a franchise system—all forms of hiring that no longer align with existing labor laws written almost a century ago, making them vulnerable to wage theft and unsafe working conditions. These jobs are the giant amoeba of the American labor market, swallowing and engulfing more and more of our workers in a huge blob of low-paying work. This reality is not reflected in TED talks, swanky ideas summits, or other intellectually elite venues where rumination about the knowledge economy, entrepreneurship, and creative destruction are de rigueur. But make no mistake, it is the economy of our present and our future.

Food and Retail Jobs

Topping the list of the largest number of jobs in the bargain-basement economy are food and retail positions, employing just over 16 million workers. These workers run the gamut from your order—taker at McDonald’s to your waitress at Olive Garden to your cashier at CVS to the salesperson at Macy’s. Of course, what they all have in common is low pay and a mandate to help satisfy our consumption needs. Back in 1970 the average American family spent most of its money on food to be eaten at home, with just 25 cents of every dollar spent on eating out. By the beginning of the millennium, 42 cents of every dollar spent on food was for take-out or dining out. And that increased demand for food on the go or a family dinner out is one reason that the so-called leisure and hospitality sector has grown from providing just 8 percent of all jobs in 1970 to providing 12 percent in 2013.

There’s an enduring image of retail and food workers as being high school or college students who cruise through during summers or work after school year-round but then kiss those jobs goodbye once they’ve earned better credentials. But like most stereotypes, this image is far from accurate. Among waiters and waitresses who are officially grown-ups—that is, aged twenty-five to sixty-four—a full eight out of ten do not have a college degree. Similarly, most retail salespeople don’t have college degrees either: 75 percent. But what about fast-food workers? Aren’t they mostly teenagers? Nothing epitomizes teen jobs more than flipping burgers or working the drive-through for any of the big fast-food companies. Well, it turns out that just 30 percent of fast-food workers are teenagers. Another 30 percent are aged twenty to twenty-four. The rest—40 percent—are twenty-five or older. And just over one-quarter of fast-food workers are parents who must rely on meager pay and unstable schedules to provide for their children.

The reality of retail workers is also quite different from the stereotype. Over half of retail workers are contributing 50 percent or more to their family’s income. And as in fast food, most of these jobs are held by adults without college degrees—defying the notion of a teen-centered workplace.

Arlene is a sixty-two-year-old African American woman who talked to me from her hospital bed after being admitted for complications from breast cancer. She recently moved in with her daughter, who is her primary caregiver as she goes through treatment. Arlene has worked in retail for nine years at the Walmart store in Evergreen Park, Illinois. She works the seven a.m. to four p.m. shift at the store, taking an hour-long journey on two buses to make it to work on time. She works as a sales associate in the electronics department but has done various jobs at the store, including being a cashier and a door greeter. Her hourly wage is $12.02, but as we’ll discuss in the next chapter, a ubiquitous challenge facing workers in food and retail is getting enough hours to earn anything close to a decent living. It’s no different for Arlene, whose hours range from twenty-four to thirty-two per week.

I asked Arlene to tell me how she felt treated on the job, and honestly, her answer startled me. She began by saying that Walmart supervisors treat her “very disrespectful, almost like a slave, I can almost relate to slavery because you don’t have any rights. I signed on to do this job the way they want it done. On the other hand, you do want to be compensated for what you bring to the table. You want to be able to take care of your basic needs, pay your rent, pay for your utilities, put food on your table. If you are in fact making billions of dollars for this company, then I don’t see what the problem could possibly be that you could take care of your basic needs and be compensated fairly. But that’s not how it is at Walmart.” Arlene, who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Chicago at the age of seventeen, today works in a job where she compares the way she’s treated to our nation’s greatest moral stain.

Arlene isn’t alone in her dissatisfaction. Various surveys find that jobs in retail and food service rank very low in terms of job satisfaction.

The Blue-Collar Jobs

In the top-ten list of occupations providing the largest number of jobs in our country, two of the ten (laborers/material movers and janitors) could be described as traditional blue-collar work, that is, physical labor done overwhelmingly by men. But unlike four decades ago, these jobs aren’t on the assembly line or factory floor. Today over 2 million people in the new working class are employed as janitors or cleaners, earning a median hourly wage of $11.27. Nearly seven out of ten of these jobs are held by men. More than half (54 percent) of these workers are people of color, with Latinos comprising 33 percent, African Americans 18 percent, and Asian Americans 3 percent. The other big occupation for working-class men today is what’s known as hand laborers and material movers, employing 3.7 million people. This is classic manual labor: moving freight or stock to and from cargo containers, warehouses, and docks. It also includes sanitation workers, who pick up commercial and residential garbage and recycling. The job requires a lot of strength, because most of the lifting and moving is done by hand, not by a machine.

When Eric runs errands after work while still wearing his uniform, people regularly come up to him to ask how they can get a job at Coca-Cola, his employer. “People have great respect for Coca-Cola and want to be part of the company,” he says. “What they don’t realize is that the company doesn’t really treat its workers well.” Eric is a general laborer at the company’s South Metro distribution center on the outskirts of Atlanta, working the night shift. He started with the 4:00 p.m. shift but now does the 8:30 p.m. to 4:30 a.m. shift. He was hired at Coca-Cola (officially known as Coca-Cola Refreshments) in October 2009 and made $11 an hour. Five years later he was at $13.40. Eric confided to me that most of his family doesn’t know how little he gets paid; they just assume he’s doing well because he works for Coca-Cola. His title, general laborer, covers a lot of different duties, from being a checker (someone who scans the inventory on delivery trucks when they come back to the warehouse to make sure there are no errors) to performing all kinds of tasks in the warehouse, including driving forklifts and unloading trucks. “Anything I’m asked to do, I pretty much do, at a general-labor pay scale.” When he started at the company, he worked as a checker, doing data entry of the drivers’ sales as they returned to the distribution center. But Eric was transferred to the warehouse, he believes in retaliation for trying to unionize the facility. Eric, an African American, is in good company in the warehouse, which was 100 percent staffed by African Americans when Eric worked there, while the managers were all white. Damon, one of Eric’s former coworkers, explained to me that in the previous year, as a result of the union activity bubbling up, Coca-Cola had brought in new supervisors for the warehouse, all of whom are African American. He told me that during his four years of working in the warehouse, only five white men had been hired for the facility.

Copyright © 2018 by Tamara Draut. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.