CHAPTER 1

OBSCURITY

The prosecutor approaches the witness box. He’s all in gray, beautifully tailored, sleek as a dolphin, cuff links, a half Windsor knot. One thing Bennet appreciates about the American legal system is that the attorneys always dress impeccably like this. The same cannot be said, by the way, about scientists. Half of why he couldn’t survive academia was because of the sartorial slobbery. Shirttails hanging out, moccasins, saggy-ass jeans. It was too much.

“Good morning, Doctor.”

“Good morning, sir.”

“Doctor, would you please state your name for the members of the jury?”

“My name is Bennet Omalu, B-E-N-N-E-T, Omalu, O-M-A-L-U.”

Already the jurors are exchanging glances. What did he say? His accent is thick. He needs to enunciate or something.

“Dr. Omalu, I’m going to ask you to speak into the microphone so all the members of the jury will be able to hear you. If you’ll wait for just a moment, I’ll give you a bottle of water.”

He waits for the water. The whites of his eyes pop like flashbulbs. His face is round, a perfect circle, like a smiley-face button on a teenager’s backpack. It might make him appear calmer than he is. Does he appear calm? Thank you, thank you. He tries to appear calm. He is almost never calm. He is a man who thinks in double exclamation points. Excitable!! Everyone tells him he looks much younger than his thirty-nine years. Maybe because he’s short, he’ll say. He’s short because they didn’t have much of anything to feed him during the war, he’ll joke. It’s not a joke, actually. His sisters think it’s funny. Anyway, he likes it when people say he looks young. Also he likes to talk about himself. I’m a Christian. I’m a humble man. I surrender to God’s mercy and love. There’s an inwardness about him, but also a happy-go-lucky veneer of innocence.

He twists the cap off the bottle of water, sips.

Honestly, right now he wouldn’t mind a cigarette. He hasn’t smoked in years, hasn’t even thought about it, but right now a cigarette might be a terrific help. Cigarettes and kola nuts were how he survived the stress of med school. The green nuts, he broke them with his thumbs, plucked the fleshy lobes, and chewed them like taffy. There is no quicker kick of caffeine than the one a man gets from kola nuts. His father and everyone in the village in Nigeria, they thought the nuts were holy. His father in his tall red hat, three feathers standing high as if touching the spirit world, saying the Ibo blessing: “Ihe dï mma onye n’achö, ö ga-afü ya.” Whatever good he is looking for, he will see it. The men washing fingers, peanut butter dip, prayers, elders in robes.

Bennet doesn’t miss any of that business. Honestly, none of it. He never wanted anything to do with those tedious old-world village rituals. He would be a man of his time. In America. Everything back home in Nigeria was about busting loose from the pettiness, the corruption, the wicked tendencies of man.

Now he’s in America, in 2008, stuck in a boiling hot courtroom in Pittsburgh, and it feels like everything is once again about busting loose from the pettiness, the corruption, and the wicked tendencies of man. The irony is not lost on him. Thank you, God. I’m grateful you got me to America. I am truly grateful. But the irony is not lost on me.

“Dr. Omalu,” the lawyer says, “would you tell the members of the jury, please, how you are currently employed?”

“I’m the chief medical examiner of San Joaquin County in the central wine valley region of California,” he says, turning then to the court reporter with that super-straight posture, typing madly. “S-A-N J-O-A-Q-U-I-N,” he says.

“How long have you been the chief medical examiner in San Joaquin?”

“My official appointment started September 1, 2007.”

“Can you tell us, please, where San Joaquin County is located, give us a sense of where it is on the map?”

“It’s about one hour east of San Francisco and about forty-five minutes south of Sacramento, which is the capital of the state of California. It’s located in the central wine valley. In San Joaquin. We produce the Zinfandel. Zinfandel red wine . . . Zinfandel grapes. You find wine in San Joaquin—”

Oh my God, shut up about the wine! What are you, the Chamber of Commerce? That was so stupid. He’s nervous. He’s so angry. He does not want to be here. He looks down, taps his feet together, reaches down to yank at one sock, then the other, wipes a speck of dust off his shiny new shoe.

He got these shoes for the trial. Black cap-toe oxfords, shiny as tar. He wanted them wider. He told the guy, he said, wider? The guy said no, they’ll stretch. But they’re not stretching. Tight, like a band across the cuneiform bones, the cuboid bone, the navicular bone. Everything feels so tight, oh my gosh! His collar. The span of pin-striped wool across his back. Everything should not feel so tight. He’s testified in court hundreds of times; he’s gotten guys off death row, for God’s sake. A courtroom is not unfamiliar territory—and this courtroom specifically, in Pittsburgh, this is the one he knows best. This is where he used to live. This is where he made his mark. He needs to just calm himself down and remember he is here because he has to be, not because he wants to be. Bennet, you are just a child of God doing your imperfect best in an imperfect world.

“Dr. Omalu,” the prosecutor says, “how long have you been living in the United States, sir, either as a student or working as a professional?”

“I came to the United States in October 1994.”

“Are you married, sir?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have any children?”

“I have a five-month-old daughter.”

“Is that your only child?”

“Yes, sir.”

“In what country were you born, Doctor?”

“I was born in Nigeria, West Africa.”

The prosecutor glances at his notes, as if planning to move on past the introductions. He has fat eyebrows. A turnip nose. The heat in the courtroom is cranked way too high, an old boiler system, so the windows are cracked and you can hear the February wind whistle.

The prosecutor is not done with the introductions. “Can you outline very briefly for the members of the jury,” he says, “what your educational background was prior to coming to the United States?”

“I attended medical school in Nigeria,” Bennet says. He explains how it works there, six years, then a clinical internship, then mandated paramilitary service—three years doctoring in a rural village in the mountains. “I was the only physician,” he says, leaning into the microphone. “My primary responsibility was to stop people from dying.”

He reaches inside his collar, pulls where it pinches. He toggles his tie. This is a full Windsor knot. Many American presidents throughout history wore a full Windsor knot. Bennet thinks Barack Obama should at least try it. But instead Obama goes for the relaxed four-in-hand knot, a much less commanding statement. Bennet keeps all his ties already tied, loosened, in his closet, ready for action. That is the secret to always having a perfect, presidential full Windsor knot.

“Dr. Omalu, correct me if I’m wrong, you’re board certified in four separate areas of pathology, is that correct?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Those are anatomic, clinical, forensic, and neuropathology.”

“Yes, sir.”

Dutifully, he explains how all that happened, coming to America, the research scholarship, the second medical degree at Columbia University.

Two medical degrees?

“Yes, sir.” He chose forensic pathology as his specialty. “A specialist in death, why and how death occurs.”

Becoming an expert in death would seem to be a counterintuitive move for a physician, a person committed to saving lives. He would need an entire afternoon to explain to the jury how he ended up doing autopsies for a living; none of this had been in his plan for his life. None of this.

“Just to round out the academic picture here,” the prosecutor says, “you are also currently finishing up one other degree?”

Two more, actually, for a total of seven. “I have a master’s in public health in epidemiology. I did that at the University of Pittsburgh. I’m also completing in May, thankfully, May of this year, a master’s in business administration at Carnegie Mellon University, which I’m happy about completing. That is it.”

“You are not going to get any more degrees?”

“No. My father said, Bennet, you should retire as a professional student when you turn forty, and I’m turning forty this year.”

Heh. A little levity. He looks over at the jury—two rows of blank faces. Do they even understand him? He knows people sometimes have a hard time.

There is one person in the courtroom who understands him. The defendant, his former boss, Dr. Cyril Wecht. He’s over there at the table, a ghost in Bennet’s peripheral vision. Bennet hasn’t even been able to look at Wecht. That is so juvenile. Come on, Bennet, just look at him.

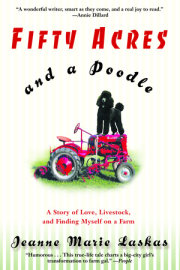

Copyright © 2015 by Jeanne Marie Laskas. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.