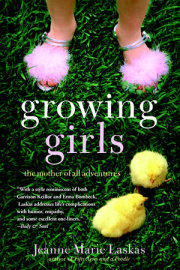

Chapter One

Okay, you go in first,” I say to Alex, the husband. He looks at me.

“I’m too shy,” I say.

He lowers his head, glares at me through eyes that say, “As if.”

Ahem. I remind him that I wet my pants nearly every day in kindergarten, so terrified was I of joining the new society of little kids.

“Yeah, well, that was a long time ago,” he says.

“Yeah, well, no one would let me go down the sliding board,” I say. I’m reaching up, trying to help tame his hair, which has suffered some severe style damage underneath the wool cap he just took off. “You have hat hair, honey,” I say.

“Oh?”

“Just kind of all over the place.”

“Oh.” He does some smoothing. “Well, I imagine this is a pretty forgiving crowd.”

We’re at our local Ramada Inn, stalled here at the entrance to Conference Room A, where the third annual Equine Clinic, sponsored by Agway, our feed and seed store, is about to begin. We’ve never been to one of these seminars before. There must be three hundred people crammed into Conference Room A. That’s more people than your mind might automatically conjure when you imagine a talk about “Pasture Management” and “Understanding Worms.”

I’m not sure I’m up for this. I was really in the mood for something low-key, like an intimate little poetry reading—except with horse talk, instead of poems.

“I’m sort of missing Sears,” I say to Alex.

“You’re missing Sears?”

“In a way . . .”

Sears is right down the road. We were just in there looking at refrigerators. And the thing is, I had an epiphany, right there in Sears. Yes, I suppose you could call it an epiphany. In my mind I am still trying to process what happened.

Nothing really happened. Alex was busy flirting with Vicki, the sales associate, trying to get her to throw in some freebies with the Amana we were considering. And I was leaning on a Maytag. I was leaning back tapping the cold enamel surface, clickety clack, clickety clack, with my fingernails. And I got to thinking. I got to thinking how blank a mind can become in the home appliance department at Sears.

Yup.

Clickety clack. Clickety clack.

And so naturally I got to wondering if there was anything at all rattling around in my big, loose brain.

And all I could think of was this: I am happy.

I am really happy.

How could such a small thought seem so huge? And—who knew? Who knew you could find yourself feeling utterly satisfied, suddenly and infinitely at peace with every promise the love gods ever promised and broke and repromised and rebroke—that whole rocky journey to love, none of it mattered now, in that instant, in that burst of awareness that really should have been happening on a beautiful mountaintop, or at least on a tropical island, no, it was happening in the home appliance department of Sears.

Is this it? That’s what I wondered. Hey, this might be it. This right here might be happily-ever-after. It might be as simple as this.

Clickety clack, clickety clack. The discovery settled a lot of doubt for me.

Because, and as you probably know, there is considerable evidence to support the notion that happily-ever-after doesn’t exist at all. Oh, plenty of people will tell you all about this. They’ll tell you that just because you happened to go into your bride stage—as I did two years ago, when I married Alex—just because you went waltzing through that garden in your satin ball gown, surrounded by swirling perfume, surrounded by your family and your friends and even Christine, your devoted hairdresser standing there armed with extra bobby pins in case of hair droops, no, it doesn’t portend anything. In fact, just because the love of your life was waiting there, in his tux, in that gazebo waiting to promise your same promise, just because that whole day went perfectly, just perfectly, right down to the clippity clop, clippity clop of the mule you got for your love as a wedding present—I got him a mule, but a small one—just because all that happiness actually happened, don’t be thinking the happiness thing will necessarily stick.

Happily-ever-after, it’s sweet. Sweet in the way a flying saucer is sweet and sweet in the way an optical illusion is sweet. It’s hope rising, then disappearing into the mist. This is the way anybody who ever tasted sour has learned to think.

It isn’t a bad way to think, but it really is only one way to think. Anyone can fall into the habit. Anyone can look at the bloom of a Shasta daisy and say, “Well, that’s not going to last.”

Why get so far ahead of the story? Why not just: Be in the story? That’s what I was thinking. I was thinking that the key to the whole thing is living in the moment, which is where happily-ever-after is, if only for the moment.

The here-and-now. I was thinking: This is the answer to everything.

So here I am now, at a Ramada Inn—I am standing here longing for the here-and-now of an hour ago at Sears.

Which would be there-and-then.

See, that’s not good.

Damn.

This is not as easy as it sounds.

Alex is still trying to mat down his poor hair. Quite a gymnastic feat, the way that hair keeps bouncing back. It’s more salt than pepper these days. It looks good on him. I mean, when it’s fixed right. Pushed back, full on the sides, curling up in the back. It’s a look befitting his character as a psychologist with wisdom and distance. Plus, he got new glasses, kind of square, fashionably hip numbers that suggest sophistication. I don’t think he looks a full fifteen years older than me. I really don’t. I’m thirty-nine. In my mind I still look like a basketball player, right guard, with a blond ponytail swishing across the number 25 on my back, and smooth skin and calves that say “athlete.” But I do have some evidence to suggest that I look different now. For one thing, it costs me eighty-eight dollars every few months to keep this hair this blond, and now it’s all layered and short, a cut designed to lift that face, yes, to draw attention to that youthful arch of those youthful eyebrows.

But I don’t mind getting old. There are plenty of things about youth that I’m glad to be done with.

“You know, I just have one comment about your whole kindergarten problem,” Alex is saying to me. (Speaking of which.) We’re still outside Conference Room A. I don’t know why he won’t go in first. Sometimes we get into these little stand-offs, which are based on nothing more than a mutually stubborn urge to win. “Did it ever occur to you that your pants-wetting thing had nothing to do with shyness,” he says, “that it was just about manipulating your poor mother?” Inhale. Exhale. See, this right here is the problem with being married to a shrink. Number one, you get sidetracked a lot. And number two, for some reason he’s always defending your mother.

“What, because she had to drive up and bring me dry underwear all the time?”

“Exactly. You had her at your command.”

Inhale. Exhale. “Honey, it was about survival,” I tell him. “It was about needing someone to rescue me from that awful, miserable place where, first of all, the teacher smelled like mothballs, and second of all, the one time I finally got the nerve to go into the bathroom, Judy Hampton tricked me into going into the boys’ room and all the kids were waiting outside laughing.”

Inhale. Exhale. Why are we even talking about this?

“Sorry,” he says.

“Well, I’ll remind you that my mom started sending me to school with dry underwear in my lunchbox—so that sort of blows your theory.”

“You know what, I’m sorry I brought this up,” he says, adding: “Did I bring this up?”

Inhale. Exhale. “What in the name of potty training do you suppose she was thinking? I mean—my lunchbox?”

Inhale, exhale, inhale.

“You know what, let’s just drop it,” Alex says.

And then he turns to go in first, which you have to admit is a gesture of something.

Conference Room A is packed, steamy. Whew, lots of body heat in here. White and green Agway balloons float optimistically above people tucked nice and tight at long tables set with Agway mugs and pencils and notepads. The walls are done up science-fair style, with display after display intending to educate on such matters as hay and sweet feed and mineral supplements and horse hair conditioners.

Alex and I don’t know a soul, as expected. The truth is, we’ve come to Equine Clinic only incidentally to learn about pasture management and worms. We’re here to participate in something, to become a part of something. This has become a sort of new campaign for us. We have been cooped up together for two happily-ever-after years. Recently we noted that we were beginning to finish each other’s sentences. Pretty soon we may start speaking our own language, like kids raised by wolves.

Cooped up together is a hazard of any happily-ever-after, I suppose, but people whose happily-ever-after happens to be set in the country, in the middle of nowhere, well, we are especially at risk.

Two years. It’s been two years since we left Pittsburgh, the familiar land of taxis and traffic lights and espresso bars and steam vents, to come to these gentle hills, about forty miles south. Hills dotted with sheep, hills that seem to roll toward Heaven itself. It was a countryside that beckoned us unexpectedly. It was a countryside that shouted: “This is it! This is your dream come true! This is the setting where your own personal happily-ever-after will take place!” Of course, this is the sort of stuff you are apt to hear when you are in a certain stage of life. When we stumbled into this area, we were just getting on with the business of being in love, we were getting married, and so of course we were getting all swept up by the adventure, by the thrill of the gamble. Some- how, when the dust from all that sweeping finally settled, we found ourselves the proud and uneasy owners of a fifty-acre farm in Scenery Hill, Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 2003 by Jeanne Marie Laskas. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.