The Lamp at Noon

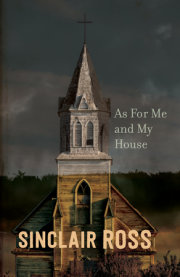

A little before noon she lit the lamp. Demented wind fled keening past the house: a wail through the eaves that died every minute or two. Three days now with out respite it had held. The dust was thickening to an impenetrable fog.

She lit the lamp, then for a long time stood at the window motionless. In dim, fitful outline the stable and oat granary still were visible; beyond, obscuring fields and landmarks, the lower of dust clouds made the farmyard seem an isolated acre, poised aloft above a sombre void. At each blast of wind it shook, as if to topple and spin hurtling with the dust-reel into space.

From the window she went to the door, opening it a little, and peering toward the stable again. He was not coming yet. As she watched there was a sudden rift overhead, and for a moment through the tattered clouds the sun raced like a wizened orange. It shed a soft, diffused light, dim and yellow as if it were the light from the lamp reaching out through the open door.

She closed the door, and going to the stove tried the potatoes with a fork. Her eyes all the while were fixed and wide with a curious immobility. It was the window. Standing at it, she had let her forehead press against the pane until the eyes were strained apart and rigid. Wide like that they had looked out to the deepening ruin of the storm. Now she could not close them.

The baby started to cry. He was lying in a homemade crib over which she had arranged a tent of muslin. Careful not to disturb the folds of it, she knelt and tried to still him, whispering huskily in a singsong voice that he must hush and go to sleep again. She would have liked to rock him, to feel the comfort of his little body in her arms, but a fear had obsessed her that in the dust-filled air he might contract pneumonia. There was dust sifting everywhere. Her own throat was parched with it. The table had been set less than ten minutes, and already a film was gathering on the dishes. The little cry continued, and with wincing, frightened lips she glanced around as if to find a corner where the air was less oppressive. But while the lips winced the eyes maintained their wide, immobile stare. “Sleep,” she whispered again. “It’s too soon for you to be hungry. Daddy’s coming for his dinner.”

He seemed a long time. Even the clock, still a few minutes off noon, could not dispel a foreboding sense that he was longer than he should be. She went to the door again – and then recoiled slowly to stand white and breathless in the middle of the room. She mustn’t. He would only despise her if she ran to the stable looking for him. There was too much grim endurance in his nature ever to let him understand the fear and weakness of a woman. She must stay quiet and wait. Nothing was wrong. At noon he would come – and perhaps after dinner stay with her awhile.

Yesterday, and again at breakfast this morning, they had quarrelled bitterly. She wanted him now, the assurance of his strength and nearness, but he would stand aloof, wary, remembering the words she had flung at him in her anger, unable to understand it was only the dust and wind that had driven her.

Tense, she fixed her eyes upon the clock, listening. There were two winds: the wind in flight, and the wind that pursued. The one sought refuge in the eaves, whimpering, in fear; the other assailed it there, and shook the eaves apart to make it flee again. Once as she listened this first wind sprang inside the room, distraught like a bird that has felt the graze of talons on its wing; while furious the other wind shook the walls, and thudded tumbleweeds against the window till its quarry glanced away again in fright. But only to return – to return and quake among the feeble eaves, as if in all this dust-mad wilderness it knew no other sanctuary.

Then Paul came. At his step she hurried to the stove, intent upon the pots and frying-pan. “The worst wind yet,” he ventured, hanging up his cap and smock. “I had to light the lantern in the tool shed, too.”

They looked at each other, then away. She wanted to go to him, to feel his arms supporting her, to cry a little just that he might soothe her, but because his presence made the menace of the wind seem less, she gripped herself and thought, “I’m in the right. I won’t give in. For his sake, too, I won’t.”

He washed, hurriedly, so that a few dark welts of dust remained to indent upon his face a haggard strength. It was all she could see as she wiped the dishes and set the food before him: the strength, the grimness, the young Paul growing old and hard, buckled against a desert even grimmer than his will. “Hungry?” she asked, touched to a twinge of pity she had not intended. “There’s dust in everything. It keeps coming faster than I can clean it up.”

He nodded. “Tonight, though, you’ll see it go down. This is the third day.”

She looked at him in silence a moment, and then as if to herself muttered broodingly, “Until the next time. Until it starts again.”

There was a dark resentment in her voice now that boded another quarrel. He waited, his eyes on her dubiously as she mashed a potato with her fork. The lamp between them threw strong lights and shadows on their faces. Dust and drought, earth that betrayed alike his labour and his faith, to him the struggle had given sternness, an impassive courage. Beneath the whip of sand his youth had been effaced. Youth, zest, exuberance – there remained only a harsh and clenched virility that yet became him, that seemed at the cost of more engaging qualities to be fulfilment of his inmost and essential nature. Whereas to her the same debts and poverty had brought a plaintive indignation, a nervous dread of what was still to come. The eyes were hollowed, the lips pinched dry and colourless. It was the face of a woman that had aged without maturing, that had loved the little vanities of life, and lost them wistfully.

‘‘I’m afraid, Paul,” she said suddenly. “I can’t stand it any longer. He cries all the time. You will go, Paul – say you will. We aren’t living here – not really living –”

The pleading in her voice now, after its shrill bitterness yesterday, made him think that this was only another way to persuade him. He answered evenly, “I told you this morning, Ellen; we keep on right where we are. At least I do. It’s yourself you’re thinking about, not the baby.”

This morning such an accusation would have stung her to rage; now, her voice swift and panting, she pressed on, “Listen, Paul – I’m thinking of all of us – you, too. Look at the sky – what’s happening. Are you blind? Thistles and tumbleweeds – it’s a desert. You won’t have a straw this fall. You won’t be able to feed a cow or a chicken. Please, Paul, say we’ll go away –”

“Go where?” His voice as he answered was still remote and even, inflexibly in unison with the narrowed eyes and the great hunch of muscle-knotted shoulder. “Even as a desert it’s better than sweeping out your father’s store and running his errands. That’s all I’ve got ahead of me if I do what you want.”

“And here –” she faltered. “What’s ahead of you here? At least we’ll get enough to eat and wear when you’re sweeping out his store. Look at it – look at it, you fool. Desert – the lamp lit at noon –”

“You’ll see it come back. There’s good wheat in it yet.”

“But in the meantime – year after year – can’t you understand, Paul? We’ll never get them back –”

He put down his knife and fork and leaned toward her across the table. “I can’t go, Ellen. Living off your people – charity – stop and think of it. This is where I belong. I can’t do anything else.”

“Charity!” she repeated him, letting her voice rise in derision.

“And this – you call this independence! Borrowed money you can’t even pay the interest on, seed from the government – grocery bills – doctor bills –”

“We’ll have crops again,” he persisted. “Good crops – the land will come back. It’s worth waiting for.”

“And while we’re waiting, Paul!” It was not anger now, but a kind of sob. “Think of me – and him. It’s not fair. We have our lives, too, to live.”

“And you think that going home to your family – taking your husband with you –”

“I don’t care – anything would be better than this. Look at the air he’s breathing. He cries all the time. For his sake, Paul. What’s ahead of him here, even if you do get crops?”

He clenched his lips a minute, then, with his eyes hard and contemptuous, struck back, “As much as in town, growing up a pauper. You’re the one who wants to go, it’s not for his sake. You think that in town you’d have a better time – not so much work – more clothes –”

“Maybe –” She dropped her head defencelessly. “I’m young still. I like pretty things.”

There was silence now – a deep fastness of it enclosed by rushing wind and creaking walls. It seemed the yellow lamplight cast a hush upon them. Through the haze of dusty air the walls receded, dimmed, and came again. At last she raised her head and said listlessly, “Go on – your dinner’s getting cold. Don’t sit and stare at me. I’ve said it all.”

The spent quietness in her voice was even harder to endure than her anger. It reproached him, against his will insisted that he see and understand her lot. To justify himself he tried, “I was a poor man when you married me. You said you didn’t mind. Farming’s never been easy, and never will be.”

“I wouldn’t mind the work or the skimping if there was something to look forward to. It’s the hopelessness – going on – watching the land blow away.”

“The land’s all right,” he repeated. “The dry years won’t last forever.”

“But it’s not just dry years, Paul!” The little sob in her voice gave way suddenly to a ring of exasperation. “Will you never see? It’s the land itself – the soil. You’ve plowed and harrowed it until there’s not a root or fibre left to hold it down. That’s why the soil drifts – that’s why in a year or two there’ll be nothing left but the bare clay. If in the first place you farmers had taken care of your land – if you hadn’t been so greedy for wheat every year –”

She had taught school before she married him, and of late in her anger there had been a kind of disdain, an attitude almost of condescension, as if she no longer looked upon the farmers as her equals. He sat still, his eyes fixed on the yellow lamp flame, and seeming to know how her words had hurt him, she went on softly, “I want to help you, Paul. That’s why I won’t sit quiet while you go on wasting your life. You’re only thirty – you owe it to yourself as well as me.”

Copyright © 2010 by Sinclair Ross Afterword by Margaret Laurence. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.