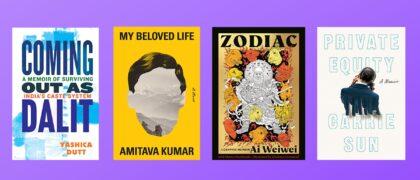

Books for National Depression Education and Awareness Month

For National Depression Education and Awareness Month in October, we are sharing a collection of titles that educates and informs on depression, including personal stories from those who have experienced depression and topics that range from causes and symptoms of depression to how to develop coping mechanisms to battle depression.