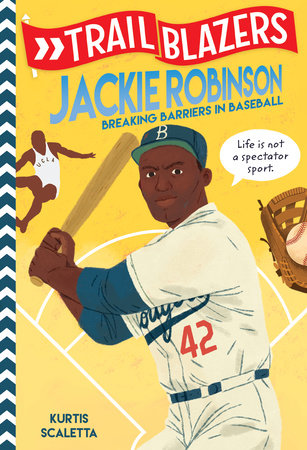

One of the most important plays in baseball history was a ground ball to third base. It was April 15, 1947: opening day at Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. A rookie named Jackie Robinson came to the plate and bounced the ball to the left side of the infield. The Boston Braves third baseman fielded the ball and threw it to first as Jackie reached the base. The fans thought Jackie had gotten to the base before the ball, but the umpire signaled an out.

“We was robbed!” Dodgers fans bellowed from the stands.

Jackie turned to glare at the umpire. For a moment it looked as if he were going to argue the call. Instead, he retreated to the dugout. It didn’t make much of a difference in the game, but it was the first time a black player had swung a bat in Major League Baseball in almost sixty years.

A Gentleman’s Agreement

Jackie Robinson was not the first black player in the major leagues. There were a few in the very early days of baseball.

WILLIAM EDWARD WHITE

First Base

MOSES FLEETWOOD WALKER

Catcher

GEORGE WASHINGTON STOVEY

Pitcher

Those were the wild and woolly early days of baseball. New teams came along every year, and other teams folded. Teams changed names and cities so often, it was hard to keep up! Entire leagues could rise to major-league status and then fall back to the minors a few years later. The rules were always changing. It took six or seven balls for a walk, instead of four, and foul balls didn’t count as strikes.

There was never an official rule against black players in organized baseball, but in 1887, team owners came to what was called a “gentleman’s agreement.” They decided no major- or minor-league team would sign another black player. So, before the baseball establishment had even agreed on how many balls made up a walk, it had decided the game was for white players only.

Over the next sixty years, baseball grew as the national pastime. Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers and later Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees were the country’s biggest heroes. Baseball stadiums became the beating hearts of most major American cities. And baseball became a big business! Larger stadiums were built so more fans could come to watch the excitement. Everywhere you went you heard the cheers and groans of games booming out of radio sets, or people talking about the local team at bus stops and cafés. By the mid-1940s, some games were on television.

Black players had their own teams and leagues but played in the shadows of organized baseball. The Negro League schedules and scores were usually not printed in the daily newspaper. The games were rarely broadcast on the radio. There was certainly no talk of televising them.

As unfair as that was, organized baseball was no different from many other institutions in America. Most of the country was deeply segregated, meaning that people of different racial backgrounds lived very separate lives.

Mr. Rickey’s Noble Experiment

During World War II, over a million black men and women served in the US military—including Jackie Robinson. Many fought and died for their country. Black Americans had shown courage and sacrifice, many white people realized, and deserved access to the American dream. Meanwhile, factories had hired blacks to work alongside whites to keep up with the demands of the war. It had worked on the factory floor—why not in baseball?

Of course, some groups, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), had been trying for decades to win justice for black Americans. Their goal was integration, meaning black people could live in the same neighborhoods, go to the same schools, and have the same job opportunities as white people did. But it wasn’t until after World War II that those efforts started to pay off.

The president and co-owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers at the time was Branch Rickey. Rickey had been a baseball executive for thirty years. He helped build championship teams in St. Louis before moving to Brooklyn.

His three favorite pursuits were:

1) doing the right thing

2) winning baseball games

3) making money

Rickey knew that bringing top talent from the Negro Leagues to the Dodgers would help him do all three at once. But he had to sign the perfect player to do it. He decided on Jackie Robinson. Jackie was not the best player in the Negro Leagues, but Rickey liked his seriousness and discipline. He liked that Jackie had gone to college and had served his country. Rickey brought Jackie to New York, saying that he was starting a new Negro League team. Once Jackie was in his office, Branch told him the truth. He wanted Jackie to play for the Dodgers!

Branch Rickey warned him that it wouldn’t be easy and that Jackie would have people yelling at him and calling him names. He told Jackie that if he let these actions get to him, or yelled, or called others names in return, people would say black ballplayers didn’t belong in Major League Baseball. If Jackie was a victim of a bad call, he couldn’t complain to the umpire. If he was treated unfairly, he couldn’t grumble to the newspapers. Jackie Robinson promised he would try.

As he walked to the dugout after his first plate appearance as a Dodger in 1947, Jackie kept his promise to Branch Rickey and to himself. He would not make waves.

He did not get a hit that day, but he drew a walk late in the game, stole second base, and then ran to third on an error. From there he scored the game-winning run. When he left the ballpark to catch a train back to his hotel, fans—white and black—surrounded him, eager to shake hands with the newest Dodger.

Jackie downplayed the significance of the game to the newspapers. He knew it was a historic moment, but he also knew that the white newspapers would make too much of it if he came across as arrogant or self-important.

Jackie Robinson had crossed baseball’s color line, but his journey was just beginning. He had played one game in front of a friendly crowd. He knew he would face bigger challenges on the road. He knew he would be mistreated by crowds in other ballparks. He knew that he would be barred from many of the restaurants and hotels other players enjoyed. He knew white reporters would watch him, waiting for him to blow his top or muff a play so they could say the experiment was a failure.

He knew he must shoulder the big load without cracking, and not just to save his own spot on the team. He had to do it to open the door for other talented black baseball players and to prove to America that integration would work.

On that chilly afternoon of his first game, Jackie didn’t know if he’d even make it through the season. He certainly didn’t know that someday he’d be one of the game’s best-ever players! On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson might have known only one thing: he would not keep silent forever. One day he would speak his mind.

Copyright © 2019 by Kurtis Scaletta. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.