Chapter 1

To understand baseball, you have to understand percentages. For example, if a guy is hitting .250, he only has about one chance in a thousand of going five-for-five in a single game. Over a season, though, the odds get better. Like about one in seven. Not great, but not that bad. If he plays long enough, he'll probably do it. That's how a guy can go into every game feeling positive. He knows if he plays enough games, eventually he'll have a perfect day at the plate.

It's the same thing with rain. Maybe you read in the paper every day that there's a 25 percent chance of rain. That means there's about one chance in a thousand of having it rain five days straight. It's not likely, but it's not impossible. If you're twelve years old, like I am, you've probably even seen it happen.

If you take all the teams in the history of baseball, then percentages start making funny things happen. For example, Walt Dropo of Detroit once got twelve hits in a row; he went five-for-five one day and seven-for-seven the next. The odds of that are like one in two million, but there's been way more than two million tries, if you think about all the baseball players and all the games they ever played in, so it had to happen eventually. Dropo was just the guy who did it.

That's how I explain the fact that it's been raining for twenty-two years in Moundville. The earth is a big place, and it's been around for a long time. If you think about all the towns in the world and all the years the earth has been around, it was bound to happen somewhere sooner or later. It just happened to be my town and my lifetime. It's percentages.

I'm trying to explain this to Adam on the last day of baseball camp while we're packing up to go home. Camp is at the state university, and we've been sharing a dorm room about the size of a breadbox.

"Everybody's hitting .250?" he asks me. "Even the DH?"

"For the sake of argument, yeah."

"Sounds like a pretty lousy baseball team." He shakes his head. "The manager would send some guys down or something. Maybe make a trade."

"That's not the point."

"It is so the point! If your whole team is batting .250, you don't wait around until the end of time because maybe eventually a guy goes five-for-five. You do something about it."

"We can't do anything about the weather, though."

"You can move."

"It's not that easy. My dad's business is in Moundville."

"He can start a business somewhere else."

"He rainproofs houses," I remind him. "It's not like there's a big demand for that anywhere else."

"I would move anyway," he says. "No baseball? That's nuts."

"It's not such a bad place to live. Anyway, there's lots of places where it rains all the time. London. Seattle."

"It doesn't rain every day for twenty-two years straight."

"It could, though."

"Whatever."

I like Adam pretty well, but I'm kind of mad at him for dumping on Moundville. Sure, it's wet, but it's still my hometown.

Fortunately, we're interrupted by a half dozen people practically knocking down the door. It's Steve and his family.

Steve is also from Moundville. We've known each other since kindergarten. His parents and his little sisters and his grandma came down to watch the Camp Classic, and now they're all heading home.

The Camp Classic is a four-team tournament meant to end camp with a bang. Adam and I were on the winning team. He pitched the first game, and I caught both games. My shins still feel like they're about to fall off at the knees, but it was worth it.

"You're coming with us!" says one of Steve's sisters. It must be Shauna because she's wearing a red T-shirt. They color-code the twins so everyone can tell them apart.

"Your dad can't make it!" the other sister, Sheila, explains.

"Shush," says their dad. "Let the man talk to his father." He passes me a cell phone.

"Yeah?" I shout into the phone.

"Hey, kid. No need to yell." My dad's voice is as clear as if he's standing right next to me, a testament to Mr. Robinson's commitment to high-end gadgetry. "I hear you won a trophy?"

"It's nothing." I figure Steve's dad must have told him about my Camp Classic MVP trophy.

"It didn't sound like nothing."

"Those trophies are like immunizations. Everybody has to get one." It's true, too. Adam won a trophy for "best competitor," which meant he took the game too seriously, and Steve won one for "best sport," which meant he didn't take the game seriously enough.

"Anyway," he says, "I've got tied up with some stuff here in Moundville, so I asked Steve's dad to give you a lift back."

"Sure. What's going on?" Usually it means someone's rainproof house is leaking and my dad has to go and fix it. He gives out a five-year warrantee that's no end of grief.

"It's kind of a surprise. You'll find out when you get home. See you soon!" He hangs up on me, and I hand the phone back to Mr. Robinson.

"Thanks for giving me a ride."

"We're happy to have you along. Maybe the girls will bug you instead of bugging the rest of us." Mr. Robinson thinks this is hilarious, and so do Steve's mom and grandma. "Anyway, we're parked right outside. See you in a bit."

We can hear the twins racing to the end of the hall and their mom begging them to slow down before the door swings shut behind them.

"So I guess I'll see you when we're in the big leagues?" Adam asks as we leave the dorm for the last time.

"Sure thing. Get drafted by the same team, okay? I don't want to hit your stuff."

Adam is the only kid I know with a legitimate curveball. I've seen him carve up batters like they were turkeys with that thing. He's small, though. You don't see too many pint-sized pitchers in the majors. So who knows if he'll make it to the bigs?

We trade a clumsy hug, and that's that.

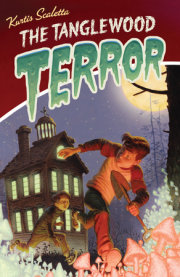

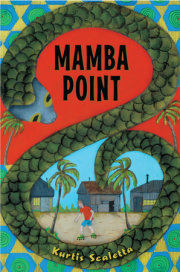

Copyright © 2009 by Kurtis Scaletta. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.