Prologue

Supposing

London. December 1850. So far it has been an unusually mild winter—in Kensington there are reports that a tree is already sending out the first green shoots of spring. Not that everyone can see them. In fact some people can scarcely see past their own feet. Fog. Its dirty fingers probe and stroke the buildings, and make a ghost of anyone who ventures outside. It muffles the sounds of everyday life: the distant cries of street sellers, the clockwork chime of church bells, the steady rattle of horse-drawn cabs punctuated by the curses of foot passengers slipping on wet pavements. It is beautiful: in some places it is pale yellow or green in colour, creating halos around the hissing gas jets and turning every street scene into an impromptu stage set. It is also dangerous: on the evening of 23 December there is a collision in “dense fog” between two trains near Brick Lane, causing many passenger injuries after a carriage is “shattered in all directions.” Fog everywhere.

Approaching the end of one year and the start of the next, the nation is getting used to seeing life as a series of pivots between the old and the new. Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace—a nickname coined that summer by the playwright and wit Douglas Jerrold—is rapidly being assembled in Hyde Park, and already it is one of the most remarkable sights in London: a giant glass bubble wrapped around a cast-iron skeleton, like an experimental skyscraper gathering its strength for a final push upwards. On the ground there is a steady bustle of activity, as girders are bolted together and glass panels are slotted into place. Excitement about the forthcoming Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations is also building. The Illustrated London News is carrying advertisements for sheet music featuring “The Great Exhibition Polka,” and it is also possible to buy a “Grand Authentic View” of the Crystal Palace engraved on steel “nearly Two Feet in Length”—although that is a mere doll’s house design compared to the real building, which when completed will be 1,848 feet long by 456 feet wide, or roughly three times the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Elsewhere things are not progressing nearly so fast. Although mortality rates are falling, the latest official statistics show that they remain considerably higher in cities like London than elsewhere in the country, largely because of the diseases spread by contaminated water and overflowing graveyards. (A recent outbreak of cholera in Jamaica has given a terrible warning of what can happen when a city is gripped by infectious disease: in Kingston more than two hundred people have been dying every day, and with no more coffins left their bodies have been rotting in heaps under the tropical sun.) In December a young servant hired from the local workhouse achieves an unhappy kind of fame when it is revealed that she has been so badly mistreated by her employers—who have starved her, beaten her, and forced her to eat her own excrement—that when she is rescued the hospital surgeon who examines her declares that she is “the most perfect living skeleton I have ever seen.” The newspapers are also full of reports describing how the convict George Hacket has recently escaped from Pentonville Prison, after levering up a part of the chapel floor and hauling himself down the prison wall using a rope made from knotted sheets; the next evening he sends a letter to the prison governor, in which he presents his compliments and announces that he is “in excellent spirits” and “in a few days intends to proceed to the continent to recruit his health.” For all the visible signs of progress—everywhere ambitious modern buildings are rising out of the rubble of construction sites, and the streets are full of fresh scars as new sewers and gas pipes are laid—in some ways not much appears to have changed since the notorious thief Jack Sheppard achieved folk-hero status by repeatedly escaping from prison more than a century earlier.

The literary world is also caught between the old and the new. At her house in Chester Square, Mary Shelley is suffering from the brain tumour that will kill her in a matter of weeks; in her writing desk is a copy of Shelley’s poem “Adonais,” wrapped around a silk parcel containing the charred remains of his heart and some of the ashes from his cremation on an Italian beach in 1822. Leigh Hunt, formerly a political radical and Keats’s literary mentor, has recently celebrated his sixty-sixth birthday with the publication of a three-volume autobiography, in which he boasts that over a career spanning more than four decades he has somehow managed to avoid ever growing up: accused of being the “spoiled child of the public,” he claims this is a title he is “proud to possess.” At the same time there are signs the Romantic age is finally giving way to a more modern alternative. Alfred Tennyson has recently become Poet Laureate, following Wordsworth’s death in April and the 86-year-old Samuel Rogers declining the office on account of his “great age,” with Tennyson only deciding to accept after Prince Albert came to him in a dream and kissed him on the cheek. (“I said, in my dream, ‘Very kind, but very German.’ ”) The same month a revised edition of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Poems is published, which now includes her Sonnets from the Portuguese, written during her courtship by Robert Browning a few years earlier; one sonnet begins “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” a line that will later be reprinted in dozens of anthologies and borrowed by thousands of tongue-tied lovers, grateful that someone else had found a way to articulate their most intimate thoughts. “The old order changeth, yielding place to new,” Tennyson had written in his 1842 poem “Morte d’Arthur.” For younger writers this has started to sound less like an elegy than a manifesto.

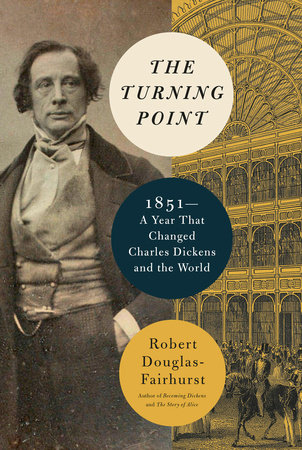

It is at this historical juncture that Charles Dickens, one of the busiest men in London and currently the most famous writer in the English-speaking world, agrees to sit for a new portrait by the painter William Boxall. The portrait is never completed, after Dickens notices that it appears to be turning into someone else. First it is the notoriously ugly boxer Ben Caunt, a resemblance that probably occurred to Dickens because of the pun lurking in the artist’s surname: at the end of December, he writes that Boxall paints like someone sparring with the canvas, repeatedly dancing backwards from it “with great nimbleness” before returning to make “little digs at it with his pencil.” Then it is the murderer James Greenacre, whose wife’s head had been found bobbing about in Regent’s Canal in 1837, and whose waxwork effigy had subsequently been displayed at Madame Tussaud’s. Finally, Dickens told the artist William Powell Frith, “I found that I was growing like it!—I thought it time to retire, and that picture will never be finished if it depends upon any more sittings from me.”

It wasn’t the only time Dickens would decide that a portrait hadn’t truly captured his likeness. In 1856 he told his friend John Forster that a painting soon to be finished by Ary Scheffer showed “a fine spirited head . . . with a very easy and natural appearance to it,” but “it does not look to me at all like, nor does it strike me that if I saw it in a gallery I should suppose myself to be the original.” A few years later he was equally suspicious of the latest engraving of a photograph taken of him. “I do not pretend to know my own face,” he told the artist. “I do pretend to know the faces of my friends and fellow creatures, but not my own.” There seems to be more going on here than the usual worry that other people cannot see us in quite the same way we see ourselves. For Dickens it was as if no artistic representation could ever depict someone with his famously fidgety energy. Kate Field, who attended Dickens’s American public readings towards the end of his career, observed that even in photographs it looked as if his soul had been “pumped out of him.”

Other images that survive from this period are no more successful. A daguerreotype probably taken in 1850 by the London photographer Antoine Claudet, still protected by its battered red leather and gilt case, shows Dickens trying to adopt a jaunty pose, with his left hand resting lightly on a side table and his right hand thrust into his trouser pocket, but he looks decidedly awkward, like an actor playing a role he doesn’t quite believe in. A drawing made the previous year by the journalist George Sala affectionately retains Dickens’s earlier pen name in depicting “ ‘Boz’ in his Study,” as the author reclines in his favourite armchair next to neat shelves of books. Yet while his legs are comfortably crossed, and his eyes gaze off thoughtfully into the distance, his right hand—his writing hand—is again hidden from view, reaching inside an embroidered dressing gown as if trying to keep a secret.

Later images would attempt to make up for Dickens’s personal elusiveness by showing him surrounded by his characters: a version of “Charles Dickens” that deliberately muddled together the man and the author who had used his fiction to scatter his personality in many different directions. By the end of his career Dickens had created around a thousand named characters; even his incomplete final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, contained at least forty, including such human oddities as Deputy, a mysterious urchin who is paid a halfpenny by another character to throw rocks at him if he ventures out after 10 p.m. And never before in the history of fiction had so many characters seemed somehow bigger than their stories. Showing them hovering around Dickens was therefore more than just a way of imagining what might have been happening inside his head. It captured the feelings of many readers that these figures seemed on the point of walking off the page and entering real life.

Contemporary verbal portraits of Dickens aren’t much better. “What a face is his to meet in a drawing-room!” wrote Leigh Hunt. “It has the life and soul in it of fifty human beings.” Other witnesses quickly realised that trying to pin Dickens down in a single description would be like grabbing hold of a handful of smoke. Surviving anecdotes from this period reveal many different versions of him: the dandy who combed his hair “a hundred times in a day”; the actor who gestured with “nervous and powerful hands” while telling a story; the stickler for accuracy who devoted his life to the creation of elaborate fictions, and yet savagely beat his son in public when he discovered that “He has told me a lie! . . . He has told his own father a lie!”

Perhaps this is why Dickens’s only surviving suit of clothes, the official court dress he bought to wear for a reception hosted by the Prince of Wales at St. James’s Palace on 6 April 1870, just two months before his death, seems curiously empty of personality without Dickens himself being present to strut about in what he humorously described as his “Fancy Dress”; set up on a stand in London’s Dickens Museum, his hand-stitched wool tailcoat with gold trim looks more like a snake’s shed skin. Nor are reports of Dickens’s usual appearance any more helpful, perhaps because he always seems to have dressed as if he was on display. Caricatures of him published during his lifetime show a man gaudily encrusted with jewellery, making him look like a real-life Jacob Marley, whose ghost enters A Christmas Carol weighed down with chains and padlocks, while in 1851 Dickens appeared at a banquet “in a blue dress-coat, faced with silver and aflame with gorgeous brass buttons; a vest of black satin, with a white satin collar and a wonderfully embroidered shirt.” “The beggar is as beautiful as a butterfly,” sniffed Thackeray, “especially about the shirt-front.”

Yet the same clothes that allowed Dickens to stand out from the crowd were also an elaborate shield he could hide behind. While his contemporaries busied themselves describing his “crimson velvet waistcoats,” “multi-coloured neckties with two breast pins joined by a little gold chain” and “yellow kid gloves,” the real Dickens could quietly slip away. Even the colour of his eyes was hard to be sure about: some people said green; others hazel, or grey, or “dark slatey blue,” or black, or a muddy combination of them all. In effect, by the end of 1850 Dickens had established himself in the public mind as something more than just another writer. He was an escape artist. Novelist, playwright, actor, social campaigner, journalist, editor, philanthropist, amateur conjuror, hypnotist: he was like a bundle of different people who happened to share one skin. Every time his contemporaries thought they’d worked out who he was, he managed to wriggle free.

Dickens sometimes enjoyed playing up to the idea that his name was a plural noun. He created multiple nicknames for himself, which in addition to “Boz” included “Revolver,” “The Inimitable” and “The Sparkler of Albion.” In the late 1840s, after making himself responsible for the stage lighting in some amateur dramatic performances, he added “Young Gas” and “Gas-Light Boy” to his growing repertoire of alter egos. He later sent a letter to one of the cast signed by all the characters he had played, including “Robert Flexible” in James Kenney’s farce Love, Law, and Physic and “Charles Coldstream” in Dion Boucicault’s comedy Used Up, with each signature being written in a distinct style of handwriting. The fact that “Charles” came directly after “Flexible” seems more than just a happy coincidence.

At the same time, he was wary of his literary identity being diluted by the work of other writers. In March 1850 he launched Household Words, a weekly journal that aimed to tackle some of the most pressing issues of the day. “All social evils, and all home affections and associations, I am particularly anxious to deal with,” he had told a possible contributor in February. In practice this meant commissioning articles that would treat even weighty subjects like poverty or sanitation reform with a light touch, combining instruction and entertainment in a way that would appeal to readers who enjoyed this mixture in Dickens’s own writing, where it formed the characteristic double helix of his style. “Brighten it, brighten it, brighten it!” he once instructed his subeditor W. H. Wills, after reading an article that was insufficiently “Dickensian”—a word that would soon be used to refer to any piece of writing that combined hard-hitting satire with sentiment and humour, whether or not Dickens himself was responsible for it. (Other coinages included “Dickensish,” “Dickensesque” and “Dickensy.”) Nonetheless he was wary of contributors who tried to flatter him by writing articles that offered little more than bad impressions of his style, like a form of literary karaoke: in one letter that summer he grumbled about the “drone of imitations of myself.”

Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.