Chapter One

The sky was milk white and vaulted. A squall tugged at the creosote and sagebrush and sent dust devils spinning off the mesas. Millennia of rain and Holy Wind, the Nilch'i Diyini had carved the washes and gulches and canyons that folded into the skin of this land.

To survey this world in the chill of November was to feel loneliness crawl into your bones. There were few creatures and fewer souls.

A distant clanking: A school bus rounded a bend and bounced down a pockmarked old Indian route past red-ribbed buttes that reared out of the earth like primeval monsters. It crossed a creek and passed a wickered grove of cottonwoods, the silver branches delicate as veins against the sky. The road heaved up and up again, and the bus emerged from a gap in an escarpment into a parched emptiness of plain that stretched to the end of vision.

The teenage boys on the bus called to one other and craned their necks and pointed at a red-tailed hawk riding the currents of approaching winter.

A painted black-and-gold wildcat with pronounced claws and fangs stretched the length of this bus, which carried Navajo boys and girls from Chinle to their season-opening basketball games. They were among the more talented players on the reservation, and this was the beginning of their quest for a state championship. The seating hierarchy was as formalized as that of a royal court. Raul Mendoza, a four-decade-long coaching force on the Navajo reservation, married to a Navajo woman yet not Navajo himself, respected although perhaps not beloved, commanded the front seat and stared impassively through dark sunglasses at the gray and rutted road. He had lived a dozen lives in seventy years of wandering. His black leather shoulder bag carried his whiteboard, his scouting reports, and a dog-eared black Bible into which he talked softly at night.

The girls' coach was a former rez ball star and a mother. She sat behind Mendoza. Girls' basketball games draw thousands of fans on the rez. The male assistant coaches sat behind her-Lenny, Bo, Julian, and Ned-big men with broad shoulders, all former hoop stars in an unspoken competition to take the helm when old Mendoza retired or got fired. The end can come suddenly in the high desert.

Teenage girls occupied the next block of seats, chatting and laughing and singing to BeyoncŽ. They knelt on seats and on the floor and braided one another's brown hair. The boys commanded the back of the bus and slouched like cats, heads and arms on each other's shoulders and backs. Some tapped out texts to buddies or girlfriends. Some listened to hip-hop on earbuds, and some stared out the window as their land, the vast DinŽtah, rolled past. Two freshmen boys, awkward fawns, had made this team and they peered, eyes wide and furtive, at the seniors, at the coach, at the girls.

All were excused early from class for the three-hour drive from Chinle, their windswept town at the sandy mouth of Canyon de Chelly, to Snowflake, a Mormon outpost on the arid plains 130 miles south.

Good luck, teachers said.

Get a win, friends said.

Play hard, parents said.

All translated into an unspoken command: You better not lose.

There was no grander sport on the reservations of the Southwest than rez ball, a quicksilver, sneaker-squeaking game of run, pass, pass, cut, and shoot, of spinning layups and quick shots and running, endless running, with an athleticism that found its origin in that Native American time before horses. Navajos learned basketball in Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools but long ago made it their own, a game played by grandparents and parents and children, men and women alike. Play was swift and unrelenting as a monsoon-fed stream. Custom dictated that players help their opponents to their feet. They as quickly knocked them down again.

Chinle High School was the largest school on the Navajo reservation. There have been many fine Wildcats teams but never one good enough to win a state championship, and the collective hunger to claim that trophy was insistent, immutable, an ache. Four thousand people live in Chinle, and on midwinter nights five thousand crowded into the Wildcat Den for big games. On the third day of basketball tryouts in early November, Mendoza waved a milling group of tryouts over to the baseline and asked: What is your goal? To get your name in the Navajo Times?

He did not wait for their answer. He had bidden goodbye to his wife for five months, and he would work every morning, afternoon, and night during the season. He would review game tape until his eyes became red and his vision grew blurry and indistinct. My goal, our goal, he told the boys, is to win a state championship. He held up his right hand and the finger with his fat state-championship ring-he was the only living coach on the rez to own one-and let the boys gawk.

"I want to get a bigger ring than this."

These teenagers were perched on that precarious cliff wall between adolescence and manhood, hand- and footholds uncertain. Soon enough they would face a primal decision: Should they leave their land, the largest and grandest Indian nation in the United States and the Navajo world of sacred peaks and spirits and clans? If they departed, if they entered college in the world of bilag‡anas, the whites, could they survive? If they thrived, could they ever truly return?

"Hey, hey, listen to this-blunt time!"

Angelo Lewis, 'Shlow, known as Big Daddy to the little kids who liked to scale his shoulders and back before games, was Chinle's big man, the center, a broad-shouldered six-foot-three junior with a perpetual half grin. He showed teammates his cell phone with a Facebook post of a black dude smoking a cigar-size blunt. Angelo was a wiseacre with a feel for the comedy of life and a sarcasm that could crack up teammates. He skipped classes, and sometimes struggled with grades, more from inattention than lack of comprehension. He should have been a senior this year, just like his friends and summer basketball buddies.

Dewayne Tom sat next to Angelo wearing a mauve sweater and dress shirt, black slacks and black dress shoes. Lean and soft-spoken, his teeth wrapped in sky-blue braces, and jittery before the season's first game, he lived in Pinon, a tough little town at the mouth of another beautiful canyon. His lack of defense confounded Mendoza nearly as much as his academics pleased his teachers. He took Advanced Calculus and dreamed of attending college in Phoenix or Flagstaff and becoming an engineer. Teachers and mentors told him to push himself and experience the world. That prospect filled him with delight and fear-like a leap off a canyon boulder into an icy mountain lake. His aunties and cousins and uncles who loved him lobbied him to stay and attend the Navajo DinŽ College, to remain on the rez. He smiled easily and his words revealed few shards of what stirred inside.

Josiah Tsosie, a senior five-foot-four point guard, sat farther back in the bus. He was one of the state's best cross-country runners, with legs and will like cords of steel. Each day in the ink of predawn he pushed himself out of bed and at on running shoes and pushed open the creaking door of his mom's trailer. He loped down a rutted road between pens with sheep barely stirring and rez dogs that growled and yapped and bolted after him. He ran to a low-slung mesa, eight miles or maybe ten or twelve. Some mornings he startled sleepy antelope and crossed paths with the trickster coyotes. When he saw them, he pulled out his corn pollen pouch and dipped his index finger in and touched the dust to his head and talked softly to the Holy People, listening in the wind for their answer.

He could be warm and introspective and suspicious and removed. He desired father figures and wondered why the most primal of all deserted him.

Cooper Burbank kept on his headphones. He had been the team's second-leading scorer as a freshman and possessed an elegant jump shot that he polished in hours of practice. Now, as a sophomore, he possessed fakes and spin moves he had yet to fully unpack. He was preternaturally calm and quiet, a tall and angular child of the Navajo northlands, an achingly beautiful and desolate corner of the rez. His parents had planted a basketball hoop in the red dirt behind their trailer within a few hundred yards of a wind-carved sandstone mesa, and Cooper wore out that hoop with shot after shot after shot. He attended a postage-stamp-size elementary school where his mother taught third grade and his father, a rodeo bull rider, was the custodian. A year ago Cooper's mom sat him down and said that he needed a bigger challenge, a high school with more course offerings and tougher teachers and a path to a four-year college. You need a mentor and coach, she told him, and this man Mendoza is a legend and will fill that role.

Cooper rested inside his silence and stared at a land elemental. An autumnal sun bathed the land in a blond light, sagebrush and goldenrod and desert grasses, and a herd of Churro sheep and their guardian dogs, which cocked their heads and sniffed at the air, trying to catch a scent of coyotes.

The bus rolled past Mitten Peak and across Wide Ruin Wash and into Holbrook, a border town beyond the southern lip of the reservation. Alcohol was banned on the reservation, and too many liquor stores in too many border towns peddled too much booze to too many stumbling natives. Navajo Boulevard was lined with gas stations and giant rubber dinosaurs and Indian jewelry shops and the adobe-brown Arizona Pawnman and cheap motels advertising cheaper off-season rates, and the boys fell silent and looked out the windows impassive and missing nothing.

Mendoza had coached in this diverse little town and won a state championship in 2011. His eldest daughter still lived here in a house he and his wife owned. He briefly coached an all-star team that featured Michael Budenholzer, who came out of this high desert town to coach the Milwaukee Bucks.

Millennia ago the Anasazi built a village here and they were followed centuries later by Pueblo tribes and then the restless and roaming Navajo. Francisco V‡zquez de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador, galloped through in the sixteenth century looking for the Seven Cities of Cibola. Gaunt and consumed by gold hunger, he wandered north until his fever extinguished on the endless plains of Kansas.

I drove this way a few weeks earlier in the company of an older Navajo, a ruminative medicine man with a handsome flush of white hair and a buckskin cowboy hat, and he talked of the melancholy that could grip his generation in autumn. This was the time of year that bilag‡ana operatives from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) used to fan out across the reservation in search of Navajo children to dispatch to distant boarding schools. Federal agents infiltrated every corner, driving out to Navajo shepherd cottages and camps. Parents watched the BIA car lights bounce along rutted roads for a long while before the cars arrived and agents opened their doors and asked if they had children, warning them not to lie. The federal agents walked around as if they owned the DinŽ, peering inside the eight-sided hogans with dirt floors that represented home and womb to Navajos.

Children came to know what the lengthening shadows of autumn presaged. When he was seven years old, the medicine man says, he spotted a BIA school bus trailing red dust like a bridal train and he took off running barefoot into a canyon until he was sheltered by its implacable walls. He took refuge the next year beneath a cliff overhang and laid his hands against the cool sandstone and listened for the heartbeat of his land. Agents found him and packed him off to school in Oklahoma.

He looked out the back window of the bus as his parents receded into the distance.

The founder of the BIA schools, an American army captain, distilled the mission in 1890: "Kill the Indian in him and save the man." That boy was a grandfather now, and he spoke fluent English as well as tonal Navajo, with its hundreds of vowel sounds, a language no easier to shed than his skin. The Indian inside did not die. It was the memories that arrived unbidden.

"The past cannot be unwoven," he said.

The boys on the bus knew these old tales of dispossession and possession and heeded them as they did the b‡h‡dzidii, the taboos. Chance Harvey, a senior shooting guard, had wrapped corn pollen into his basketball socks that morning. Josiah had placed a pouch of protective bitterroot in the pocket of his shorts. Most families asked medicine men to sing Protection Way songs for their boys before the season starts, the singing and chants stretching through the fire burning night until dawn cracked open the sky. Navajo oral culture was a rope that stretched through a thousand years, and another thousand, and a thousand before that, tales passing from ancestors to grandparents to a mother whispering to a baby in her womb.

Yet the broader world intruded, pushed insistently. Dewayne, Will, and Chance played Kanye and Kendrick and Lil Uzi Vert on their iPhones, and Josiah and Angelo practiced handshakes, mimicking the elaborate pregame rituals of NBA players. Grandparents and many parents could converse in Navajo, while most of the boys speak just fractured pieces of their ancient language. Dewayne knew more words than most. Sometimes he dreamt in Navajo. He dreamed recently of winter; he told me the Navajo language has fifty words for snow. These boys were migrants in time.

Old man Mendoza confused them. He pushed them to run in practice until they gasped and gagged, and they didn't always get the point of his speeches and barbed observations. They were not sure what to make of it when the coach invited them, one by one, to sit in his concrete pillbox office and talk life and hoops. They knew this, however: Mendoza had won a championship. He knew the path, and he might yet serve as their guide if they let him in.

Three hours into their trip, the WildcatsÕ bus accelerated down a smooth stretch of state-tended asphalt and crossed a broad, flat valley with dusty washes and tree-lined fields crowded with longhorns. The bus turned onto SnowflakeÕs Main Street, and the boys peered through windows at a Norman Rockwell fantasy. Immaculate old brick homes with sweeping wood porches and ice-cream parlors and a grand temple of the Latter-day Saints. Blond boys rode skateboards on sidewalks burnished burnt orange by the sun. Erastus Snow, a Mormon apostle, founded this town with his partner, William Jordan Flake, who later served time in Yuma penitentiary for the crime of taking a few too many wives. A UFO abduction supposedly took place nearby; a local logger named Travis Walton got beamed up. It brought a measure of fame to Snowflake, although some residents remained skeptical that Walton truly went intergalactic.

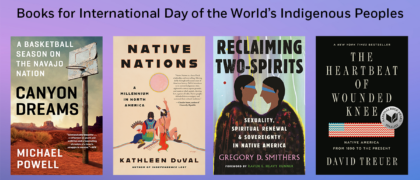

Copyright © 2019 by Michael Powell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.