ONEThe Lay of the LandI believe that stories have this power—they enter us, transport us, they change things inside us, so invisibly, so minutely, that sometimes, we’re not even aware that we come out of a great book as a different person from the person we were when we began reading it.

Julia Alvarez

THE MOMENT YOU lay down your first words of fiction, you become a magician like David Copperfield. Through the alchemy of craft and story, you create an illusion where the reader suspends disbelief, just as Copperfield makes his audiences believe he’s made a Boeing 747 airplane disappear.

Modern neuroscientists have discovered what ancient shamans have known all along: Stories have power. Power to heal, to destroy, and to change history. In fact, fiction may have a longer-lasting effect than magic. Thought releases brain chemicals and neural electricity. Stories can “get under the skin” and integrate into the interior landscape of the self—and perhaps of the soul.

We writers receive no greater compliment than to have our readers lament the ending of a story. Imagine how you would feel knowing that your characters—their lives, dilemmas, and triumphs—live on in the memory of your readers side by side with memories of actual people and situations.

Stories move people to think and act. Anaïs Nin said, “What we are familiar with we cease to see. The write shakes up the familiar scene, and as if by magic, we see a new meaning in it.” Art, in the form of a story well told, may literally transform the reader and the culture from the inside out. “A book ought to be an ice pick to break up the frozen sea within us,” said Franz Kafka. Stories hold the power to transform the very society they are said to reflect, making storytelling among the highest of callings.

The Language of Fiction

Some writers may consider the distinctions between situation and story, plot and story, and promise and theme as splitting hairs. However, understanding the language of craft and how it operates in the creation of fiction is as important as a musician learning to read notes and play scales. Incident, situation, plot, story, protagonist, antagonist, promise, and theme all establish the foundation upon which you can build any story you might want to write. Before we go any further, let’s define some of these important ideas.

STORY AND PLOT

The child tucked into bed asks her mother, “Will you tell me a story?” The mother reads “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” or “Hansel and Gretel,” or perhaps the mother makes up a character and story, as many parents do. We all grow up with a sense of story, but what, in a technical sense, does story mean to a writer?

In this book, story means the deepest meaning of a tale, while plot refers to the characters and the events that fulfill the story in a specific way. Story is deep; plot is mechanical, even if it is complex. Story is universal; plot is particular. Snow White and her friends, the dwarves, interact in a plot that demonstrates a story about trust. Hansel and Gretel experience a number of incidents that demonstrate a story about adversity and survival.

Story is deep; plot is mechanical.

Story is universal; plot is particular.

Many beginning fiction writers create characters who act and are acted upon, but in the end, they have no story. They have a set of incidents that make up a plot. This is no surprise when you think about it. It’s one thing to watch a magic trick that looks so easy; it’s another to carry it off yourself.

For instance, my friend Betty and I take Riley, my Border collie, on a walk. She and I discuss going to a movie on Wednesday night. I glance down the path and recognize an old boyfriend. As we greet each other, Riley chases a squirrel. After awhile, Betty and I finish our walk and return home.

Is this a story? No. Is it a plot? No. What I have shared is a situation and some incidents. Daily life is filled with as many incidents as you care to identify: getting dressed, going to work, talking with friends. All kinds of situations arise from the incidents of our lives. They range from the walk with my friend and dog to someone cutting you off in traffic to an unexpected check—or bill—arriving in the mail.

A situation can become a plot once you have someone with a problem or conflict who seeks an outcome to resolve it. Let’s revisit my situation with the many incidents.

I go for a walk with Betty because I am lonely. I ask her if she wants to see a movie on Wednesday night, but she’s busy. We encounter my old boyfriend John and stop to talk. Betty knows I was crushed when he stopped seeing me because I wasn’t “the one.” He is obviously taken by Betty, and by the end of the conversation, he asks for her phone number. While I’m busy chasing Riley, who has run after a squirrel, John asks Betty to go to a movie on Wednesday night. Betty looks my way, then turns to him and says, “Sure.”

Characterization, not plot, is the source of a writer’s greatest magic.

What I’ve described here is a plot. You have a character with a problem. She’s lonely and seeks her friend’s company. She pursues a solution—sharing a movie. You have opposition to her attempt to resolve her problem—her friend can’t go. You have a further complication when the old flame makes her loneliness deeper by showing interest in her woman friend. You have deeper emotional conflict yet when Betty reverses her availability and accepts his invitation.

Is it a story? When I added the deeper emotional context of loneliness and the yearning for human companionship, along with the acceptance and caring that friendship implies, it became a story. Are you wondering what happens next? If so, I’ve begun making magic. You have, at least partly, suspended disbelief in the fictitious world and through curiosity, have shown your willingness to pretend my story is real. Why have you done this? I would bet that you, too, have experienced times of loneliness, the need for human companionship, and the comfort of belonging through friendship. These are universal human needs. You can relate vicariously because my story is your story.

Will you be transformed? Will you carry away some nugget of realization or learning that will transcend this particular story? Currently, I’ve left you midstream, in the middle of the conflict. The end of the story would determine what the main character learned. Told artfully, a story can move you and alter your brain chemistry. You might make different choices in your life as a result. By my story, not by my plot, you might be transformed.

CHARACTER

Most stories have two levels: the external plot events and the internal character need. Both levels culminate in the character—and reader—learning something fundamental about self and life. Inner and outer; outer a reflection of inner. The oft-repeated reference to a character-driven plot refers to the inner story about character that always underlies and propels the outer plot events. Characterization, not plot, is the core of successful fiction. Characterization, not plot, is the source of a writer’s greatest magic.

Not all characters are of equal importance or equally developed. Yet all characters you choose to include in a short story or novel should be necessary and not extraneous. Take J.R.R. Tolkien’s masterpiece trilogy, The Lord of the Rings. Frodo may be the protagonist, but Gandalf, Gollum, Sauron, and the rest of the giant cast are completely necessary. Or take a story with a more limited cast such as Stephen King’s The Green Mile. The protagonist, Paul Edgecomb, is defined in his role as a head prison guard by the new prisoner, John Coffey, a seven foot, 350-pound soft-spoken man who is scared of the dark and who has the God-given gift to feel the soul of a person.

Just as an adventurer studies maps before beginning a trek, the fiction writer must learn to recognize the landmarks that define the terrain of story. The star of your story is called the protagonist and is often the most fully developed of all of the characters in a story. Notice the prefix, “pro,” which refers to the necessity of your star being forsomething. This something is the story goal that when reached defines the end of a story. A mystery detective searches for a murderer and seeks to bring him to justice. A young woman seeks a worthy man to fall in love with and marry. A spy infiltrates the enemy and discovers key information to block the detonation of a nuclear device.

The antagonist (ant: meaning “against”) is the character equal in force to the protagonist but who blocks his or her efforts to reach the story goal. A murderer eludes the detective and tries to kill him. A worthy man misunderstands a young woman’s actions and thinks she doesn’t want him. An enemy figures out who the spy is and tries to kill him before he finds and divulges their secrets. Antagonists typically have less development than protagonists and possibly less than other characters. They may or may not have a point of view.

Point of view refers to the development of a character within a scene, usually offering that character’s thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, actions, and reactions. The many possible points of view are covered in chapter six.

Major characters, who may or may not also be point-of-view characters, are allies to the protagonist or antagonist. They may be fully developed, although they will not have as much development as the protagonist.

Minor characters are not typically granted a point of view—unless this serves a story purpose. They may appear once or many times in a story, often in functional or job roles, but their scant development—in most stories—parallels their importance in the story. The butler may have “done it,” but in most stories, he is only a butler. However, minor characters may have viewpoints in certain kinds of stories, such as thrillers, where viewpoints are often unlimited.

STORY STRUCTURE

These terms are the landmarks of characterization. Others define structure. A series of incidents strung together is called episodic structure. Episodes or situations are not the same as stories with plots. A story with a plot, dramatic structure, features a protagonist who identifies a problem and pursues a goal that would resolve the problem. Conventional short stories and novels alike usually display basic dramatic structure. Life, which constantly presents situations and incidents, i.e. episodic structure, also dishes out multiple problems. Fiction, structured dramatically, unlike life, targets one primary problem.

In general, this primary problem springs from an inciting incident. In other words, an inciting incident isn’t any ole distressing event; it is the one that lands the “big kahuna” problem in the lap of the protagonist. This primary problem must be resolved at the end of the story, at the climax.

A story with a plot, dramatic structure, features a protagonist who identifies a problem and pursues a goal that would resolve the problem.

For instance, in The Goose and the Golden Egg, the farmer (protagonist) is desperately poor (story problem). A stranger arrives at his farm and gives him a goose that lays golden eggs (inciting incident). He cashes in on the golden eggs, day after day, and becomes rich (false hope). Then he gets the bright idea to speed up the one-egg-at-a-time process by ripping open the belly of the goose to get lots of eggs (the climax). Not only does he not find any cached eggs, he has killed the golden goose that made him rich, and in no time at all, he is once again poor.

In Wally Lamb’s This Much I Know Is True, Dominick’s schizophrenic twin brother severs his hand (inciting incident), although he does not die. For the rest of the book, Dominick (protagonist) must learn to deal with the emotional loss of his brother and his feeling of failed responsibility to protect him (problem). The climax and resolution of this novel of many layers does not come until Dominick learns who their father was and deals with fatherhood on many levels.

The story problem defines the protagonist’s story goal. Everything that happens in the plot, from the inciting incident to the climax, defines the story arc. The “everything” in-between is chock-full of problems, crises, and important but lesser goals than the singular “story goal.”

While your readers may be entertained by all of the external trappings (i.e., the plot) of your short story or novel, they can be emotionally and alchemically transformed only if you develop the inner story that is at the heart of any writing and that is the source of your writer magic. Nothing motivates a protagonist as strongly as an unquenchable need rooted in suffering that originates in the past. The inner story is the protagonist’s psychological or spiritual struggle to fulfill the need.

All human beings yearn for fulfillment of basic needs that go beyond physical survival. The resource box below provides examples of universal needs in some of our best-known novels.

Nothing motivates a protagonist as strongly as an unquenchable need rooted in suffering that originates in the past.

Bill Johnson, author of A Story is a Promise, describes a story promise as a protagonist’s fulfillment of an unmet issue of human need. In other words, by the end of A Wrinkle in Time, Charles must fulfill his need to love. By the end of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Frodo must find the courage to challenge an adversary far beyond his strength. I call this need the “story yearning.” It is the parallel of the inner character story to the outer plot goal.

Every work of fiction has many implied promises to the reader—consistency in genre, style, and tone; the logical progression of events; and unity of theme. The biggest promise, however, is to share the story journey, with clarity of yearning and goals, with your reader.

Not only can stories entertain, they can heal and enlighten. The ancient shamans knew this in a way that modern storytellers have forgotten. While life is murky, a well-told story offers a clear meaning that can transform readers in ways that transcend entertainment. To the extent that your reader shares the story yearning of the protagonist, may even have suffered a similar trauma in the past, the reader can share the protagonist’s fulfillment and resolution.

UNIVERSAL NEEDS STORY PROMISES IN LITERATURE

belonging: Harry Potter series, by J. K. Rowling

family unity: A Thousand Acres, by Jane Smiley

family history: Song of Solomon, by Toni Morrison

love: A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L’Engle

emotional healing: The Prince of Tides, by Pat Conroy

redemption: A Map of the World, by Jane Hamilton

justice: To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

freedom: The Hunt for Red October, by Tom Clancy

loyalty: A Perfect Spy, by John le Carré

survival of kin and clan: The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck

faith: Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, by Judy Blume

racial equality: Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison

friendship: Bridge to Terabithia, by Katherine Paterson

The meaningful message at the core of an entertaining or enlightening story is a story’s theme, and every well-written piece of fiction has one—just one. In this sense, fiction stops short of life, which has multiple, and often contradictory, messages. For a story to be clear, effective, and meaningful, whether a short story or an epic, it must illuminate one thematic message. Theme is the intellectual counterpart of the story yearning with its roots in universal needs.

For instance, Charlotte’s Web, by E. B. White, has a story promise about friendship, something all of us need. However, a thematic statement might read: “Charlotte’s Web describes how devotion and sacrifice on behalf of a friend can bring unforeseen rewards of spirit.” A thematic statement for A Perfect Spy, by John le Carré, could read: “The only thing that can be counted on is loyalty between men.” As a reader, you need not agree with a theme. If the writer has created an authentic protagonist, you can, at a minimum, experience enlargement of your understanding of life and the reality of others in it.

Where to Begin

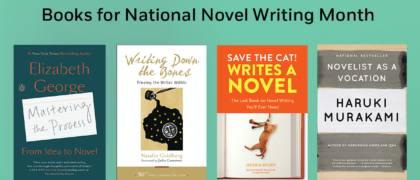

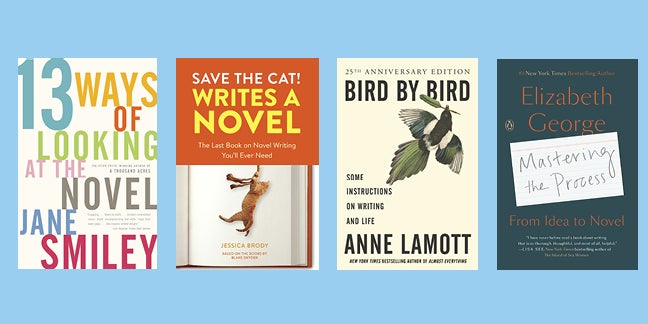

If you are new to writing fiction, you may wonder if there is a right way to “find” a story, to know how best to plan a story. The answer may not be a comfort to everyone: There is no right way; there is only your way. Anything can and has inspired writers and given them the kernel from which they’ve developed a story. No matter where you begin, you will have to fill in all the blanks. In other words, if you begin with plot, you still have to create characters, a story arc, and story promise. And so on. Map 1-1 offers sources of story ideas. There are so many helpful books on finding and developing story ideas; Map 1-2 offers a large sampling.

There is no right way; there is only your way.

The next chapter introduces the first of several chapters on characterization. If you are among those writers who conjure plots before creating characters, first read chapters three and four on story structure. Even though almost all fiction is ultimately character-driven, there is room for the writer who is a “plot monster,” like Michael Crichton, whose characters in his novels such as Jurassic Park or Airframe play an important but secondary role to plot.

For any writer who seeks to learn the fundamentals of craft, characterization done well creates some of the most powerful magic a storyteller can hope to create. If you would like to focus on developing your characters, somewhat separate from plot, first read chapters two, four, six, and seven, which are meant to help you develop characterization in progressively deeper ways.

Know that with knowledge and skill, you create magic, and with magic, you hold the capacity to make a difference in the lives of your readers, a heady responsibility with an unforeseen reward: You, not just your reader, will also be transformed.

Sources of Story Ideas

SourceExamplea phrase or verseall the queen’s men as the night follows day Jack be quickan evocative word or phrasesanguine quotidian into the nightan imagea homeless man Van Gogh’s Starry Night a shoe in the middle of the roadadvice columnex-husband proposes to ex-wife Korean-American is victim of slurs teenage girl struggles with chastityTV or newspaper reportreunion of two Holocaust survivors foster child drowns in swollen river hackers crash CIA computerspersonal experiencedetained at Checkpoint Charlie only white at a black college in 1968 reunion with first-grade boyfriendhistorical event or periodfirst moon landing fall of Berlin Wall lifetime of Pancho Villaconversation with a friendwhat if at 2 P.M., everyone is nude Christ returns as a Muslim a woman is elected presidenta strong feeling or beliefthere are no accidents greed threatens America’s stability Homo sapiens is an unstable hybridGenerating Ideas—Recommended Books

Ayan, Jordan. Aha! 10 Ways to Free Your Creative Spirit and Find Your Great Ideas

Bender, Sheila & Christi Killien. Writing in a New Convertible with the Top Down: A Unique Guide for Writers

Bradbury, Ray. Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity

Bryant, Roberta Jean. Anybody Can Write: Ideas for the Aspiring Writer, the Beginner, the Blocked Writer

Cameron, Julia. The Artist’s Way and The Right to Write: An Invitation and Initiation into the Writing Life

Carroll, David L. A Manual of Writer’s Tricks: Essential Advice for Fiction and Nonfiction Writers

Cook, Marshall. Freeing Your Creativity: A Writer’s Guide

Downey, Bill. Right Brain Write On! Overcoming Writer’s Block and Achieving Your Creative Potential

Edelstein, Scott. The No-Experience-Necessary Writer’s Choice

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers

Gelb, Michael J. How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day

Goldberg, Natalie. Writing Down the Bones and Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life

Golub, Marcia. I’d Rather Be Writing: A Guide to Finding More Time, Getting More Organized, Completing More Projects, and Having More Fun

Henry, Laurie. The Novelist’s Notebook

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

Le Guin, Ursula K. Steering the Craft: Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Navigator or the Mutinous Crew

Perry, Susan K. Writing in Flow: Keys to Enhanced Creativity

Peterson, Lois J. 101 Writing Exercises: To Get You Started & Keep You Going

Reeves, Judy. A Writer’s Book of Days: A Spirited Companion & Lively Muse for the Writing Life

Smith, James V., Jr. Fiction Writer’s Brainstormer

Wood, Monica. The Pocket Muse: Ideas & Inspiration for Writing

TWO

Finding the Characters for Your Story

I want to be able to write so powerfully, I can break the heart of the world and heal it . . . remake it.

Dorothy Allison, Skin: Talking About Sex,

Class, and Literature

CHARACTERIZATION IS THE bedrock of fiction and the reason most people read it. What endures in our hearts and minds over time is the heroes, heroines, and villains. Less often do we recall their plots. The fiction writer’s greatest challenge is character development. How many of the following characters do you recognize? Dorothy, Glenna, Harry Potter, Bilbo Baggins and Frodo, Hannibal Lecter, Rabbit, Quoyle, David Carraggio, Sula, Sethe, Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call, Garp, Kabuo, Tita, Jick McCaskill, Tom Wingo, Jack Ryan, Sherlock Holmes, Scarlet and Rhett, Kinsey Millhone, V. I. Warshawski, Nero Wolfe, and Jonathan Livingston Seagull. For every character you recognized, now summarize his or her plot.

Most people can more easily describe characters than plots. (But did you find, as I did, that your recall of plot or story is higher when you’ve also seen the movie?) Characters based on stories outlive plots.

What Makes a Character?

Every fiction writer must answer one critical question before all others: What makes characters so memorable that they outlive their creators? In former classes I’ve taught on characterization, my students have diligently sought an answer. Although “memorable” must be defined quite differently across cultures, and from one person to the next, we managed to agree on the following qualities:

- Characters are larger than life and live outside social norms and conformity in some way.

- They evoke reactions in others, often creating empathy.

- They have one particular dimension of their personality that is strong—so much so that it may make them single-minded and self-absorbed—yet they typically attract and inspire others.

- They often have a passion and depth of feeling that they “wear on the outside.”

- They nearly always have a contradiction that is at odds with their beliefs or passions.

- They may have an unusual or prominent sense of humor.

- Overall, they tend to be unapologetically and unself-consciously themselves.

- They seem to have more courage of self-expression to pursue their passions, but in truth, their drives and personality may give them no other choice.

Characters are larger than life and live outside social norms and conformity in some way.

When you can replace each general statement with specifics that describe your protagonist, antagonist, and other main characters, you will be well on your way to creating a character that will outlive you. Anyone who writes a series, for instance, understands the need to create a strong and distinctive character to “carry” the series.

Writing from the Inside Out

For some time, I’ve identified two ways to construct realistic characters. To make characters live and breathe, writers must write “from the inside out” and “from the outside in.”

From the inside out refers to making a conscious connection between your inner emotions, needs, and thoughts and the same in your characters. Anyone can create an entertaining character off the top of their head. However, the story people that will move readers—make them laugh, cry, fear, and exult—spring from deep inside their creators.

Most writers have heard the expression “thinly veiled autobiography,” referring to the idea that we project ourselves and our life experiences into the stories we call fiction. Usually, the use of this expression brings a laugh. Why? Because many people assume that an autobiographical story is of lesser quality than one freed of the “ties that bind.”

To make characters live and breathe, writers must write “from the inside out” and “from the outside in.”

I agree that when fiction writers simply re-create their lives and personas on paper, the result is rarely successful. Why? Because fiction is a selective representation of reality. The art of fiction directs the readers’ focus on highly specific details carefully chosen for their meaning, story value, and relevance to a singular story goal. Everything else is extraneous. The best fiction is free of the fetters of reality. Yet, fiction divorced from an author’s emotions and spirit comes across like a soulless zombie. Even so, many writers struggle with expressing emotion and spirit.

HARVESTING THE EMOTIONS

Writing from the inside out takes courage. It also takes careful listening to your inner responses. Take a draft of a story you’ve written, read it aloud or silently, but read it slowly. Place your full attention on what emotions surface as you let yourself become, vicariously, your character. As your character runs into opposition from others and the environment, how do you feel? Pause and “harvest” all of your feelings and thoughts. Note them, then read on and do the same for the next sentence, paragraph, or section.

What most of my students report is that their stories have many events that trigger a host of emotions, few of which make their way onto the page. The late Jack Bickham, a writing instructor and novelist, discussed “stimulus” and “response.” When you create an event in your story, especially a dramatic or upsetting event, it is a stimulus that requires a response from your point-of-view character.

Characters can’t live and breathe from now into eternity unless they feel, and feel deeply. Be their response ever so small, such as a raised eyebrow or a verbal “yeah, right,” to be believable, your characters must constantly show their humanity. Emotion is what moves most readers to care, but readers have sophisticated bullshit meters and will recognize and reject inauthentic emotion. The real deal comes from the inside out, and you are the source of your characters’ reality.

Examples abound, but think about distinctiveness of character and how emotion is evoked as you read the following example, the beginning of Annie Proulx’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Shipping News.

Copyright © 2004 by Elizabeth Lyon. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.