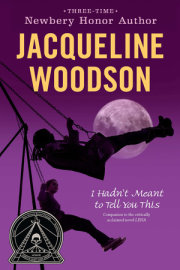

Copyright © 2018 Jacqueline Woodson

4

If there’s one thing I

do remember as clear as if it happened an hour ago, it’s the afternoon when Ms. Laverne said to us,

Put down your pencils and come with me. It was the end of September and we had been taking a spelling test. Esteban had been absent for days, and when he finally returned, Ms. Laverne asked him if he was up to doing some work and he nodded.

It helps me forget for a little while, he said.

Forget what? Amari asked.

That nobody knows where they took him. And now we’re packing up everything, Esteban said.

Because if they took him, maybe they’re going to take us too. I turned back to my test. I didn’t want to think about fathers. Mine had been in prison for eight years by then. In the last letter we’d gotten, he said he wasn’t sure what would happen with his parole. If he got it, he didn’t know exactly when he’d be coming home. I remember zero about living with him. Every good thing that happened had happened with my uncle. I couldn’t imagine a different life. Didn’t want to imagine it. Not for me. Not for anyone.

I was stuck on the word

holiday. Did it have one

l or two? My spelling had always been bad, but in Ms. Laverne’s class it didn’t matter so much because we were all at different levels in one thing or another.

The words you miss just tell me what you don’t yet know, Ms. Laverne always said.

It says nothing about who you are. For some reason that made me feel better. I was eleven years old. What eleven-year-old didn’t know how to spell

holliday?

Put down your pencils and come with me.The six of us stood up. Our school uniforms were white shirts and dark blue pants or skirts. We could wear any jackets, shoes and tights we wanted. I had worn blue-and-white-striped tights that day. Holly’s tights had red stars on them. When we stood next to each other in the school yard that morning, our stars and stripes echoed the flag waving from the pole above us. We had spent the minutes before the bell rang dancing around it while Holly sang that old song about having a hammer,

I’d hammer out danger, I’d hammer out a warning . . .

We stood next to our desks and waited for Ms. Laverne to tell us what to do next. Amari pulled his hoodie over his head, then quickly pulled it off again, the way he sometimes did when he was nervous. Amari was beautiful. His skin was so dark, you could almost see the color blue running beneath it. His eyes were dark too. Dark like there was smoke behind his pupils. Dark and serious and . . . infinite. In that fifth/sixth grade class, I didn’t know how to say any of this. I wanted only to look at him. And look at him.

Take a picture, it lasts longer, Amari said to me in such a cranky way, it almost brought me to tears. Ashton smirked, then pushed his hair away from his forehead and held his hand there.

She doesn’t want a picture of you, Holly said.

Bad enough we have to look at you five days a week. She had left her desk and was heading over to the classroom library.

Holly, back to your desk, Ms. Laverne said.

I want you all to take your books. You won’t be coming back here today.We all gathered our stuff and followed her into the hallway.

Ms. Laverne took out her phone and said,

Smile, people. In the photo, Holly and I have our fingers linked together, our tights looking crazier than anything. Amari has his hood halfway on and halfway off, and Tiago, Esteban and Ashton are all looking away from the camera. The picture is taped to my refrigerator now. We all look so young in it, our cheeks puffing out with baby fat, our uniform shirts untucked, Tiago’s sneakers untied.

We walked down the hall behind Ms. Laverne, her heels softly clicking. I thought about how maybe one day I’d grow up to wear black shoes with small heels that clicked as I walked down a hall. And have students following behind who were a little bit in love with me.

Two small kids came running down the hall, but when they saw Ms. Laverne, they stopped and started walking so slowly, I almost laughed.

Esteban pulled his knapsack onto his shoulder and held it with both hands.

You okay, bro? Amari put his hand on Esteban’s arm.

Nah, Esteban said.

Not really. Amari moved his arm over Esteban’s shoulder. And kept it there.

5

When we got to Room 501, Ms. Laverne opened the door and held it for us. Nobody knew what to do, so we just stood there. The room was bright and smelled like it had just been cleaned with the same oil soap my uncle used on our floors. Back when me and Holly were in third grade, it had been the art room, but then someone gave our school enough money to open up a whole art studio in the basement, so now this was just a room we passed by sometimes and said to each other,

Remember when that used to be the art room?

Welcome to Room 501, Ms. Laverne said.

Holly ran in ahead and the rest of us followed and looked around.

In the old art room, there were just a few of those chairs with swing-up desks in a circle, a teacher’s desk with no chair, a big clock on the wall and some little kid’s ancient painting of a bright yellow sun thumbtacked to the closet door.

Esteban asked,

Are we getting transferred to a new class? He put his knapsack down between his ankles and hugged himself.

Amari had taken his arm off Esteban’s shoulder but was still standing close to him. When Esteban shivered, Amari put his arm back. I heard him whisper,

It’s all good, bro. It’s all good. Ms. Laverne’s not taking us somewhere we don’t want to be.Ms. Laverne sat on the edge of the teacher’s desk and folded her arms.

Every Friday, from now until the end of the school year, the six of you will leave my classroom at two p.m. and come into Room 501. You’ll sit in this circle and you’ll talk. When the bell rings at three, you’re free to go home.

Why can’t we just talk in our regular classroom? Holly asked, hopping up onto the teacher’s desk.

I mean, in your classroom.Our regular classroom wasn’t regular. We knew that. But still.

Down from there, please, Holly. Ms. Laverne waited for Holly to jump off again before she continued.

I don’t want to hear what you have to say to each other. This is your time. Your world. Your room.

Sounds like you’re trying to get an early break from us, Holly said.

Give yourself your own kind of half day.Ms. Laverne laughed.

One day, Holly, your brain will be very useful to you.Holly looked like she wasn’t sure if our teacher was complimenting her.

What I’m trying to do is give you the space to talk about the things kids talk about when no grown-ups are around. Don’t you all have a world you want to be in that doesn’t have people who look like me in it?

Nope, Amari said.

Yeah, Ashton said.

Not really.

We like being with you, I added.

In the other room.

You like what you know, Ms. Laverne said.

You like what’s familiar.None of us said anything. She was right. What was wrong with liking familiar things?

Nothing’s wrong with that, Ms. Laverne said, being a teacher/mind reader.

But what’s unfamiliar shouldn’t be scary. And it shouldn’t be avoided either.

But I don’t know what we’re even supposed to talk about, Tiago said.

Like, schoolwork and stuff? And to who?

Schoolwork, toys, TV shows, me, yourselves—anything you want to talk about. To each other. And it’s to whom

, Tiago.

To whom, Tiago said to himself like he was practicing it.

To whom.I think any other bunch of kids would have started happy-dancing and acting crazy because there weren’t going to be any grown-ups around. But we weren’t any other kids.

I heard Amari say

that’s stupid so quietly that I wondered if I was hearing things. Then he said,

We could be talking in class if we wanted to be talking. You trying to change the art room into the A-R-T-T room—A Room To Talk.

That’s tight, Ashton said. He and Amari pounded fists.

I like that.Ms. Laverne clapped once and pointed at Amari.

You. Are. Brilliant.

I could have come up with that. Holly rolled her eyes.

I could have added an R

and thrown an acronym out there. She said

acronym loudly, making sure Ms. Laverne heard.

Nice use of the word, Holly, Ms. Laverne said.

Okay, so because the art room is now the A-R-T-T room, no one gets in trouble for talking here. You get in trouble for taking out your phone. You get in trouble for being disrespectful—

How’re you gonna know if you’re not in here with us? Amari asked her.

I’ll know.And we all knew she was telling the truth. Teachers knew things. That’s all there was to it.

Well, what if I don’t have anything to say to anybody? Amari asked.

Ms. Laverne laughed again.

Since when do you not have anything to say, Amari? She shook her head and waved her hand to include all of us.

I can’t believe you all are so resistant. I’m giving you an hour.

To chat! You get in trouble for this every single day. How many times do I have to say ‘No talking’? Now I’m saying, ‘Talk!’Amari tried to hide his smile but he didn’t do a great job of it.

Okay . . . I’m vibing it. The old art room is the new A-R-T-T room, y’all.

And I bet you can draw in here too, if you want, Ashton said to him.

Ms. Laverne nodded.

Draw, talk. And yes, Amari—the A-R-T-T room is beyond clever.

Like I said, anybody could have thought of that, Holly said.

Yeah—but I see YOU didn’t, Amari said.

And like I said, Ms. Laverne told us,

in this room we won’t be unkind.

She started it—

Doesn’t matter, Amari.

I just want to get it straight, Ashton said.

So, school now ends at two o’clock on Fridays?He had pale white skin like my uncle, and hair that always fell into his eyes. Even as he asked, he was holding it back with his hand. Once Holly had said to him,

Just cut it already, and his ears turned bright red. My own hair had always been bright red, but lately it had started getting darker and kinkier. If Holly’s mother didn’t braid it for me, I just pulled it back into a sloppy ponytail that frizzed all around my face.

Jeez, Ashton! Holly said.

That’s not what she’s saying. This is so not deep, people.

I just don’t really understand why we’re going into another room, Ashton said,

by ourselves. I think, looking back on that day now, that’s the line that will always stay with me—

another room, by ourselves. How many other rooms by ourselves have we walked into since that day—even if they weren’t real rooms and we didn’t know that’s what we were doing?

I stood there thinking about my father. In six months or a year—I didn’t know exactly when—I’d be walking into another room, the one where my father lived with me. And as I stood there, Esteban was inside the room where he didn’t know where his dad was. He glanced at me. That day, no one but Holly knew that my dad was in prison. I felt like I was betraying Esteban. Like I should have been standing next to him, saying,

Hey, it’s gonna be okay. But I couldn’t. I couldn’t tell the truth about my dad to help him. So I looked down at my skirt and thought about rooms. I wondered about Tiago, Holly, Amari and Ashton—what were the rooms for them? What did they hide inside those rooms? Another room, I thought. We are always entering another room.

That day, Ms. Laverne pushed us out—from the Familiar to the Unfamiliar.

It felt like an hour passed as she waited for us to say something. I looked at the clock. The second hand made an echoing sound when it ticked. It was five minutes past two. Fifty-five minutes left.

You can do this, Ashton. You all can do this, Ms. Laverne finally said. And with that, she walked away. With that, she let us go.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.