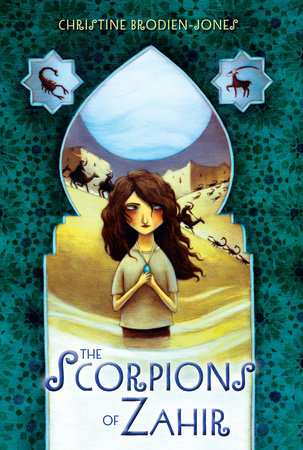

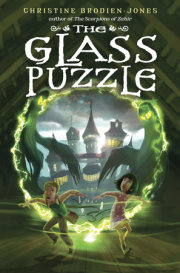

THE ORYX STONE AND THE SCORPION

Zagora Pym sat with a beat‑up leather-bound book open on her lap, dreaming about Zahir. She’d found the book the day before when her father was lecturing at the university and she was snooping around his study. It was at the bottom of his desk, in a drawer crammed with pencils, graphs and navigational charts. On the first page were spidery letters that read Excavating Zahir: The Journal of Edgar Q. Yegen, Intrepid Explorer.

She perched on the edge of her bed, slowly turning the pages, which threatened to fall apart at the slightest touch. Zagora was eleven and a bit rough around the edges, with perpetually scraped elbows, a face with sharp angles and a gap between her teeth, and she wore the gaze of a constant dreamer. She knew that while she might not be a ravishing bandit princess or a girl genius with an off-the-charts IQ, she had adventure in her heart, and to her that’s what mattered most.

Most of the journal’s pages looked chewed up--she guessed by desert beetles--and many were damaged or missing. But that didn’t stop Zagora from reading the pages that were left. And although the ink had faded, she could see that the paragraphs had been composed by a precise and scholarly hand, in the language of a particular time.

The book started off with the paragraph:

I begin this journal on a blustery March day in Boston, Massachusetts, sitting in my study overlooking Marlborough Street, in the year 1937. In two months’ time a freighter will leave Boston Harbor for the port of Tangier, Morocco--and I will be on it. This expedition will be the culmination of ten years of exhaustive research, which began the moment I discovered the infamous Oryx Stone.

Zagora had never read anything so thrilling in her life. Her archaeologist father often talked about his adventures in Zahir, including his role in the failed expedition to excavate the buried city. But the entries in this book went all the way back to 1937!

In Edgar Yegen’s journal there were accounts of moonless black nights in the desert, open-air markets and the bleak Atlas Mountains. She studied his sketches of mud-walled houses, patterned archways, an underground tomb. It was easy to imagine the sun, the insects, the heat and dust of the Sahara. She read about the road to Zahir, with its stone columns, snaking through yellow sands. What excited her most, though, were the entries about a mysterious object called the Oryx Stone.

She stopped flipping the pages of the book right where Edgar Yegen first described the strange stone, and read the entry again.

While roaming the casbah in search of a comfortable pair of slippers, I happened upon a makeshift stall containing the kinds of trinkets one encounters in these bustling markets. Tipping my hat to the proprietor, I was about to walk away when a flash of blue caught my eye. Amid the tangle of evil-eye charms, worry beads and ankle bracelets was the most extraordinary necklace I had ever seen: strung on a ribbon of leather was a blue stone the size of a robin’s egg with the tiny figure of an oryx--an animal considered sacred by the ancient tribe of the Azimuth--etched into the center. I held the stone in my hand and my blood quickened. I intuited that this was indeed a long-lost treasure: the infamous Oryx Stone, stolen centuries ago from the legendary city of Zahir.

The description of the Oryx Stone matched that of an object she’d found in her attic years earlier. While searching for an explorer’s headlamp to wear in the cellar on a newt-catching expedition, she had opened a steamer trunk and discovered, under a stack of archaeology magazines, a tattered drawstring pouch.

Tucked inside the pouch was a luminous stone the same ice blue as her eyes. Similar to a small egg in shape and size, the stone was polished smooth and threaded on a worn leather string. If she turned the stone a certain way in the light, she could see the image of an oryx, her favorite desert animal, which had been cut into the surface of the stone.

Ever since that day, late at night, when her dad and brother were asleep, she would creep up to the attic and pull out the stone, mesmerized by its ethereal light. She’d spent hours up there, exploring foreign lands, inventing stories of far-off places, dangerous bandits, magical oryxes and lost desert opals. Riding imaginary camels, she made journeys in her goggles, pith helmet and crocodile boots, which came to a frightening point at the toe. And always, always, she wore the glowing blue stone.

There was a knock at the front door and Zagora guiltily closed the journal, tucking it under her bed. She planned to return it to her father’s desk before he discovered it was missing, though it was likely he’d forgotten he even had it. Her dad was absentminded that way.

Bounding downstairs and out to the front porch, she found a huge envelope stuffed in their mailbox. Her father was always getting weird-sized parcels sent from all over the world. This envelope had a weary look, as if it had been traveling for years and years, space-warping to their house from another century.

“Dad, package!” she shouted, bursting into her father’s study, where he sat playing Desert Biome Madness on his computer.

Charles W. Pym, PhD, DSc, a tall, introspective, first-class archaeologist (in Zagora’s opinion) and translator of rare glyphs, was now in the later stages of his career. Zagora bragged to her friends that her father tracked down snow leopards in the Gobi, dynamited a buried fortress in Mali and almost died of thirst while measuring wind patterns in Egypt. His career had been a series of worst-case scenarios, she explained, using his phrase. She didn’t know the specifics, but she liked the way the words sounded.

Dr. Pym spun around in his ergonomic bungee chair and Zagora ceremoniously handed him the envelope. It was stamped with the words Royaume du Maroc, which she knew meant “Kingdom of Morocco.” The hand-writing was messy and the stamps were desert themed, with whimsical pictures of lizards, camels, hyenas and insects that she was dying to collect.

“Can I keep the stamps?” she asked eagerly. “They’re really cool.” Ever since she was seven, when her dad had brought home a book called Flora and Fauna of the Sahara, she’d immersed herself in facts about deserts of the world.

Her father held up the brown envelope tied with string. “What’s this, eh?” He squinted at the return address. “Who could be sending me a package from Morocco?”

“Maybe they want you to set up a desert expedition,” suggested Zagora. It was always an event when her dad landed a job, especially in some exotic location.

She watched his face carefully as he scrutinized the old-fashioned script through his drugstore reading glasses, the lines around his eyes deepening.

“Good grief.” He gave a puzzled frown as he tore open the envelope. “Hmmm. I don’t recognize the sender’s address--”

Copyright © 2012 by Christine Brodien-Jones. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.