“Force . . . equals . . . mass . . . times . . . acceleration,” muttered Ada as she wrote in her notebook. Ada pondered that if you drop a hammer on your foot, it hurts more than dropping, say, a sock on your foot. The acceleration, or speeding up, is the same, but the mass, the solid oomph of a thing, is different. Oomph times zoom equals kaboom!

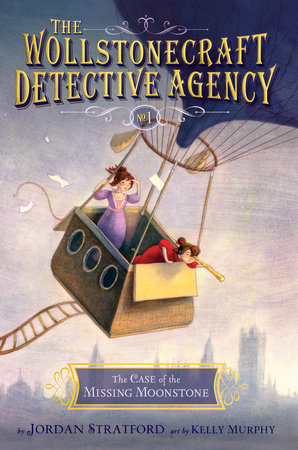

Ada and her pondering were cocooned in a square wicker box that resembled a giant picnic basket, just tall enough for her to stand up in and long enough for her to lie down in. Light entered through round, brass-ringed windows and lit up stacks of books, rolls of paper, the odd screwdriver, and a bundle of pencils. The basket hung from thick ropes beneath a vast patchwork balloon that often swayed savagely in the wind, and the whole contraption was tethered with more ropes to the roof of Ada’s Marylebone house in the heart of London.

The balloon was one of Ada’s best inventions. It was filled with hot air from the house’s many chimneys, which Ada funneled to it via numerous pipes bolted together. Taken as a whole—pipes, ropes, basket, and balloon—it gave the impression that the stately house was wearing a sort of ridiculous hat.

Ada lay stretched out on the gondola’s floor in her favorite cherry velvet dress, which stopped a full inch above her ankles and showed wear and the odd black grease stain. Her hair was dark brown, almost black, and pulled back into a bun, with little wisps here and there trying to make a run for it.

What if, Ada wondered in her wicker box, you could accelerate a sock? What if the sock were moving so fast that it could have the same force as a hammer? Would it hurt the same? How fast would the sock have to go, and how could you make a sock go that fast?

Ada thought like this all the time. And to capture her thoughts, she made drawings—little sketches in notebooks or on scraps of paper or on table linens or, once (at a very dull picnic and much to the displeasure of her recently former governess, Miss Coverlet) on Ada’s new dress. The drawing of the moment was a sock cannon of Ada’s invention.

The sock cannon was taking shape on paper and in between Ada’s ears. But as busy as her ears were containing the sock-cannon plans, she could make out the sound of a carriage approaching the Marylebone house.

Grabbing a brass telescope that had been rolling about on the floor with the swaying of the basket, she stood and flipped open the hatch. She climbed up the three-step rope ladder to the balloon’s short deck, from which she could see as far as Oxford Street. She could see down Wimpole and Welbeck, Wesley and Westmoreland, down Weymouth and Cavendish and Queen Anne and even the little lanes off Baker Street. Only she and the crows knew her neighborhood in this way, from above.

Her stomach tightened. Walking across busy Marylebone Road, carpetbags in hand, went Miss Coverlet for the last time, leaving Ada alone for good.

Ada had to admit that “alone” was not entirely accurate. The house in London was staffed by two women whose names she could never quite remember: Misses Cabbage and Cummerbund, or possibly Arugula and Aubergine—she honestly had no idea. When food arrived—with the exception of the bread and butter she’d help herself to in the upstairs kitchen—it was at the hands of Miss Coverlet, or Ada’s very tall and entirely silent butler, Mr. Franklin. And then the dishes went away, seemingly by themselves, to a place where she supposed something or other must happen to them.

But as far as Ada was concerned, without Miss Coverlet, whom Ada had known all her life, who had comforted her scrapes and answered her questions and fetched her favorite books and made sure her stockings weren’t scratchy—something Ada hated rather desperately—yes, Ada would feel utterly alone.

At eleven, Ada was deemed too old for a governess, and was now to have a tutor instead. A tutor! Ada knew it was impossible for any living person to educate her. For that, she had her books. Books for learning, books for distraction, books for company, books for making sense of things. Ada’s books were full of facts and figures, diagrams and calculations. Books that were not to be argued with. Books that stayed put when you needed them to and didn’t run off to get married, as Miss Coverlet was off to do, which seemed to Ada like the stupidest idea ever.

In most matters, Ada was a genius. Once the facts and figures and charts and calculations from her books wandered into her head, they never left it. Even when she was a baby, Ada had loved number games and puzzles. She fixed things that were broken, and then began fixing things that weren’t broken, or broke things so they could be fixed in ways no one else understood or found particularly convenient. But the one puzzle she couldn’t solve was people. To Ada, they all seemed to be broken in ways she couldn’t make sense of, and couldn’t fix.

Right now there was the puzzle of her heart, which was breaking as Miss Coverlet stepped aboard the carriage.

“I’m going to my balloon,” Ada had said when informed of Miss Coverlet’s departure that morning. She supposed that Miss Coverlet might have mentioned getting married before, but Ada hadn’t realized that meant she’d be leaving and that leaving meant alone. And she certainly hadn’t known Miss Coverlet would be leaving today.

Ada knew that if she was to be alone, then the drawing room, with its grand wallpaper and curlicued gilt frames, its lush Indian carpet and scattering of delicate china, was not where “alone” was going to happen.

Miss Coverlet had watched Ada turn and leave, stomping just a little bit for show. Miss Coverlet had seen some very expert stomping from Ada over the years, and this stomping seemed halfhearted.

Indeed, as Ada now watched Miss Coverlet leave in the carriage, she felt that she had only half a heart left.

Ada had barely returned to her sock-cannon plans when she heard the great black lion’s-head knocker strike the front door.

Whoever it was had best go away. She wanted to be left alone—alone as Miss Coverlet had left her, here in her safe wicker fort beneath her balloon, tethered with strong nautical rope to the topmost peak of her house. While she knew she should slide down the rope to the widow’s walk and swing into the attic window as she’d done a hundred times before, she felt safest here, basket swaying, with her inventions and her books and her drawings. No, she would not come down.

Not ever.

Copyright © 2015 by Jordan Stratford. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.