CHAPTER 1

Down Twenty-three Steps

At midnight, Yakov Yurovsky, the leader of the executioners, came up the stairs to awaken the family. In his pocket he had a Colt pistol with a cartridge clip containing seven bullets, and under his coat he carried a long-muzzled Mauser pistol with a wooden gun stock and a clip of ten bullets. A knock on the prisoners’ door brought Dr. Eugene Botkin, the family physician, who had remained with the Romanovs for sixteen months of detention and imprisonment. Botkin was already awake; he had been writing what turned out to be a last letter to his own family.

Quietly, Yurovsky explained his intrusion. “Because of unrest in the town, it has become necessary to move the family downstairs,” he said. “It would be dangerous to be in the upper rooms if there was shooting in the streets.” Botkin understood; an anti-Bolshevik White Army bolstered by thousands of Czech former prisoners of war was approaching the Siberian town of Ekaterinburg, where the family had been held for seventy-eight days. Already, the captives had heard the rumble of artillery in the distance and the sound of revolver shots fired nearby on recent nights. Yurovsky asked that the family dress as soon as possible. Botkin went to awaken them.

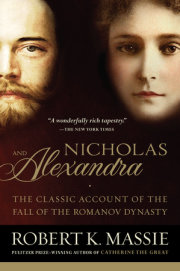

They took forty minutes. Nicholas, fifty, the former emperor, and his thirteen-year-old son, Alexis, the former tsarevich and heir to the throne, dressed in simple military shirts, trousers, boots, and forage caps. Alexandra, forty-six, the former empress, and her daughters, Olga, twenty-two, Tatiana, twenty-one, Marie, nineteen, and Anastasia, seventeen, put on dresses without hats or outer wraps. Yurovsky met them outside their door and led them down the staircase into an inner courtyard. Nicholas followed, carrying his son, who could not walk. Alexis, crippled by hemophilia, was a thin, muscular adolescent weighing eighty pounds, but the tsar managed without stumbling. A man of medium height, Nicholas had a powerful body, full chest, and strong arms. The empress, taller than her husband, came next, walking with difficulty because of the sciatica which had kept her lying on a palace chaise longue for many years and in bed or a wheelchair during their imprisonment. Behind came their daughters, two of them carrying small pillows. The youngest and smallest daughter, Anastasia, held her pet King Charles spaniel, Jemmy. After the daughters came Dr. Botkin and three others who had remained to share the family’s imprisonment: Trupp, Nicholas’s valet; Demidova, Alexandra’s maid; and Kharitonov, the cook. Demidova also clutched a pillow; inside, sewed deep into the feathers, was a box containing a collection of jewels; Demidova was charged with never letting it out of her sight.

Yurovsky detected no signs of hesitation or suspicion; “there were no tears, no sobs, no questions,” he said later. From the bottom of the stairs, he led them across the courtyard to a small, semibasement room at the corner of the house. It was only eleven by thirteen feet and had a single window, barred by a heavy iron grille on the outer wall. All the furniture had been removed. Here, Yurovsky asked them to wait. Alexandra, seeing the room empty, immediately said, “What? No chairs? May we not sit?” Yurovsky, obliging, went out to order two chairs. One of his squad, dispatched on this mission, said to another, “The heir needs a chair . . . evidently he wants to die in a chair.”

Two chairs were brought. Alexandra took one; Nicholas put Alexis in the other. The daughters placed one pillow behind their mother’s back and a second behind their brother’s. Yurovsky then began giving directions—“Please, you stand here, and you here . . . that’s it, in a row”—spreading them out across the back wall. He explained that he needed a photograph because people in Moscow were worried that they had escaped. When he was finished, the eleven prisoners were arranged in two rows: Nicholas stood by his son’s chair in the middle of the front row, Alexandra sat in her chair near the wall, her daughters were arranged behind her, the others stood behind the tsar and the tsarevich.

Satisfied by this arrangement, Yurovsky then called in not a photographer with a tripod camera and a black cloth but eleven other men armed with revolvers. Five, like Yurovsky, were Russians; six were Latvians. Earlier, two Latvians had refused to shoot the young women and Yurovsky had replaced them with two others.

As these men crowded through the double doors behind him, Yurovsky stood in front of Nicholas, his right hand in his trouser pocket, his left holding a small piece of paper from which he began to read: “In view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.” Nicholas turned quickly to look at his family, then turned back to face Yurovsky and said, “What? What?” Yurovsky quickly repeated what he had said, then jerked the Colt out of his pocket and shot the tsar, point-blank.

At this, the entire squad began to fire. Each had been told beforehand whom he was to shoot and ordered to aim for the heart to avoid excessive quantities of blood and finish more quickly. Twelve men were now firing pistols, some over the shoulders of those in front, so close that many of the executioners suffered gunpowder burns and were partially deafened. The empress and her daughter Olga each tried to make the sign of the cross but did not have time. Alexandra died immediately, sitting in her chair. Olga was killed by a single bullet through her head. Botkin, Trupp, and Kharitonov also died quickly.

Alexis, the three younger sisters, and Demidova remained alive. Bullets fired at the daughters’ chests seemed to bounce off, ricocheting around the room like hail. Mystified, then terrified and almost hysterical, the executioners continued firing. Barely visible through the smoke, Marie and Anastasia pressed against the wall, squatting, covering their heads with their arms until the bullets cut them down. Alexis, lying on the floor, moved his arm to shield himself, then tried to clutch his father’s shirt. One of the executioners kicked the tsarevich in the head with his heavy boot. Alexis moaned. Yurovsky stepped up and fired two shots from his Mauser directly into the boy’s ear.

Demidova survived the first fusillade. Rather than reload, the executioners took rifles from the next room and pursued her with bayonets. Screaming, running back and forth along the wall, she tried to fend them off with her armored pillow. The cushion fell, and she grabbed a bayonet with both hands, trying to hold it away from her chest. It was dull and at first would not penetrate. When she collapsed, the enraged murderers pierced her body more than thirty times.

The room, filled with smoke and the stench of gunpowder, became quiet. Blood was everywhere, in rivers and pools. Yurovsky, in a hurry, began turning the bodies over, checking their pulses. The truck, now waiting at the front door of the Ipatiev House, had to be well out of town before the arrival in a few hours of the July Siberian dawn. Sheets, collected from the beds of the four grand duchesses, were brought to carry the bodies and prevent blood dripping on the floors and in the courtyard. Nicholas’s body went first. Then, suddenly, as one of the daughters was being laid on a sheet, she cried out. With bayonets and rifle butts, the entire band turned on her. In a moment, she was still.

When the family lay in the back of the truck, covered by a tarpaulin, someone discovered Anastasia’s small dog, its head crushed by a rifle butt. This little body was tossed into the truck.

The “whole procedure,” as Yurovsky later described it, including feeling the pulses and loading the truck, had taken twenty minutes.

Two days before the executions, Yurovsky and one of the other executioners, Peter Ermakov, a local Bolshevik leader, had gone into the forest looking for a place to bury the bodies. About twelve miles north of Ekaterinburg, in an area of swamps, peat bogs, and abandoned mine shafts, there was a place known as the Four Brothers because four towering pine trees had once overlooked the site. Around the stumps of these old trees, and among the birches and pines which grew there now, were empty pits, some shallow, some deeper, from which coal and peat had once been dug. Abandoned, some had filled with rainwater and become small ponds. The largest of these, named after a peasant prospector, was called Ganin’s Pit. Nearby, other smaller, deeper mines were nameless. It was to this place that Yurovsky brought the bodies.

Already deep in the forest, jouncing through the darkness along a muddy, rutted road, Yurovsky’s truck suddenly encountered a party of twenty-five men on horseback and in peasant carts. Most were drunk. They were factory workers from the town, some of them members of the new Ural Regional Soviet, tipped off by their comrade, Ermakov, that the Imperial family would be coming down that road. But they had expected to see the family alive; Ermakov had promised his friends the four grand duchesses as well as the thrill of killing the tsar. “Why didn’t you bring them alive?” they shouted.

Yurovsky, in control, calmed the angry men and ordered them to shift the bodies from the truck into the carts. In the process, the workers began stealing from the victims’ clothing and pockets. Yurovsky halted this by threatening an immediate firing squad. Not all of the bodies would fit into the small carts, and some remained on the truck; in tandem, this macabre procession continued into the forest.

In the darkness, surrounded by dense pines and birches, the party could not find the Four Brothers. Yurovsky sent horsemen up and down the road looking for the turnoff to the site. When the sun began to rise and the forest grew light, they located it. The road became only a track, and soon the truck had wedged itself between two trees and could go no farther. More bodies were heaped into the carts. At six in the morning, the procession reached the Four Brothers. Ganin’s Pit, nine feet deep, had a foot of water in the bottom. Not far away, in another, narrower mine shaft, cut thirty feet into the earth, the water was deeper.

Yurovsky ordered the corpses laid out on the grass and undressed. Two fires were built. As the men were stripping one of the daughters, they found her corset torn by bullets. From the ripped slash gleamed rows of diamonds sewed tightly together—the “armor” which initially had shielded her from bullets and astonished her executioners. Sight of the jewels excited the men; again, Yurovsky moved quickly and dismissed all but a few, sending them back down the road. The undressing continued. Eighteen pounds of diamonds were collected, mostly from the corsets worn by three of the grand duchesses. The empress was found to be wearing a belt of pearls made up of several necklaces sewed into linen. Each of her daughters wore around her neck an amulet bearing Rasputin’s picture and a prayer by the peasant “holy man.” These jewels, amulets, and anything else of value were placed in sacks, and everything else, including all clothing, was burned.

The naked bodies lay on the grass. All had been violently disfigured. At some point in the carnage, perhaps in maniacal rage, perhaps in a deliberate attempt to make the corpses unrecognizable, the faces had been crushed by blows from rifle butts. Nevertheless, as the six women—four of them young and, twelve hours earlier, beautiful—lay on the ground, their bodies were touched. “I felt the empress myself and she was warm,” said one of the party later. Another said, “Now I can die in peace because I have squeezed the empress’s ——.” The last word in this sentence is crossed out.

Once the bodies were stripped, the jewels collected, and the clothing burned, Yurovsky was almost finished. He ordered the bodies thrown down the smaller, deeper mine shaft. Then, attempting to collapse the pit, he dropped in several hand grenades. By ten in the morning, his work was done. He returned to Ekaterinburg to report to the Ural Regional Soviet.

Eight days after the murders, Ekaterinburg fell to the Whites and a group of White officers rushed to the Ipatiev House. The building was mostly empty. Toothbrushes, pins, combs, hairbrushes, and smashed icons were scattered on the floors. Empty hangers hung in the closets. Alexandra’s Bible still was there, heavily underlined, containing dried flowers and leaves pressed between its pages. Many religious books also remained, along with a copy of War and Peace, three volumes of Chekhov, a biography of Peter the Great, a volume of Tales from Shakespeare, and Les Fables de la Fontaine. In one bedroom, the officers found a smooth-edged board on which the tsarevich had eaten and played games in bed. Nearby was a handbook of instructions for playing the balalaika. In the dining room near the fireplace stood a wheelchair.

The room in the cellar seemed sinister. A few traces of dried blood still clung to the baseboards. The yellow floor, thoroughly mopped and scrubbed, bore scratches and dents from bullets and lunging bayonets. The walls were scarred by bullet holes; from the wall against which the family had been standing, large pieces of plaster had fallen away.

An immediate search for the family led nowhere. Not until six months later, in January 1919, did a thorough investigation begin when Admiral Alexander Kolchak, “Supreme Ruler” of the White Government in Siberia, assigned Nicholas Sokolov, a thirty-six-year-old professional legal investigator, to the task. As soon as the snow melted, Sokolov began working at the Four Brothers. The track through the forest still showed deep ruts from the carts and the truck. The earth around the pits had been trampled by horses’ hooves. Cut branches and burned wood floated on the surface of Ganin’s Pit and the narrow mine shaft. The walls of the deeper pit showed evidence of grenade explosions. There were traces of two bonfires, one at the edge of the narrow mine, the other in the middle of the forest road.

Sokolov ordered the water pumped out of Ganin’s Pit and the nameless mine shaft and began to excavate. In Ganin’s Pit he found nothing, but from the other he collected dozens of articles and fragments. In this grim work he was assisted by two of the tsarevich’s tutors: Pierre Gilliard, whose subject had been French, and Sidney Gibbes, who had taught English. Both had remained in Ekaterinburg after the Imperial family was sent to the Ipatiev House. Among the evidence identified and cataloged by these heartbroken men was the tsar’s belt buckle; a child’s military belt buckle which the tsarevich had worn; a charred emerald cross which the Dowager Empress Marie had given to Empress Alexandra; a pearl earring from a pair always worn by Alexandra; the Ulm Cross, a jubilee badge adorned with sapphires and diamonds, presented to the empress by Her Majesty’s Own Uhlan Guards; a metal pocket case in which Nicholas always carried his wife’s portrait; three small icons carried by the grand duchesses; the empress’s spectacle case; six sets of women’s corsets; fragments of the military caps worn by Nicholas and his son; shoe buckles belonging to the grand duchesses; and Dr. Botkin’s eyeglasses and upper plate with fourteen false teeth. There were also a few charred bones, partly destroyed by acid but still bearing the marks of an ax; revolver bullets; and a severed human finger, slender and manicured as Alexandra’s had been.

Sokolov also collected an assortment of nails, tinfoil, copper coins, and a small lock, which puzzled him until they were shown to Gilliard. The tutor immediately identified them as part of the pocketful of odds and ends always carried by the tsarevich. Finally, at the bottom of the pit, mangled but unburned, the investigators found the decomposed corpse of Anastasia’s spaniel, Jemmy.

But other than the finger and the charred bones in the pit, Sokolov found no human bodies or bones. He interrogated one of the executioners and numerous corroborating witnesses and established that eleven people had been killed at the Ipatiev House. He knew that the bodies had been brought to the Four Brothers. He learned that on the day following the murders, two more trucks carrying three barrels had gone down the Koptyaki road into the forest. He discovered that two of those barrels had been filled with gasoline and one with sulfuric acid. Accordingly, Sokolov concluded that on July 18, the day after the execution, Yurovsky had destroyed the bodies by chopping them up with axes, dousing them repeatedly with gasoline and sulfuric acid, and burning them to ash in bonfires near the mine shafts. These ashes and bones he declared to be the remains of the Imperial family, the site of the bonfires to be their grave.

Reverently, Nicholas Sokolov placed the physical results of his investigation—the charred bones, the finger, and the principal personal articles—inside a suitcase-sized box. In the summer of 1919, when the Red Army surged back into Ekaterinburg, Sokolov traveled across Siberia to the Pacific and went by boat to Europe. His box, later to become an object of mystery and contention, went with him.

When in 1924 he published his conclusion, skeptics argued that it was not possible to burn eleven corpses so completely in a bonfire. Nevertheless, Sokolov’s story was buttressed by his simple, seemingly indisputable statement: there were no bodies.

For most of the twentieth century, this is what the world believed.

Copyright © 2012 by Robert K. Massie. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.