I

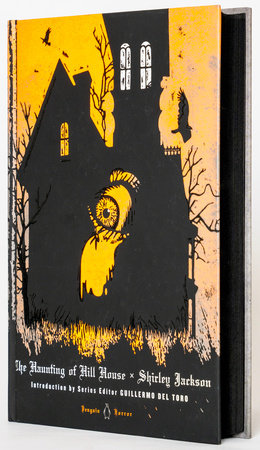

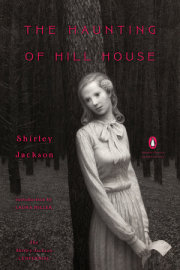

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

Dr. John Montague was a doctor of philosophy; he had taken his degree in anthropology, feeling obscurely that in this field he might come closest to his true vocation, the analysis of supernatural manifestations. He was scrupulous about the use of his title because, his investigations being so utterly unscientific, he hoped to borrow an air of respectability, even scholarly authority, from his education. It had cost him a good deal, in money and pride, since he was not a begging man, to rent Hill House for three months, but he expected absolutely to be compensated for his pains by the sensation following upon the publication of his definitive work on the causes and effects of psychic disturbances in a house commonly known as “haunted.” He had been looking for an honestly haunted house all his life. When he heard of Hill House he had been at first doubtful, then hopeful, then indefatigable; he was not the man to let go of Hill House once he had found it.

Dr. Montague’s intentions with regard to Hill House derived from the methods of the intrepid nineteenth- century ghost hunters; he was going to go and live in Hill House and see what happened there. It was his intention, at first, to follow the example of the anonymous Lady who went to stay at Ballechin House and ran a summer- long house party for skeptics and believers, with croquet and ghost- watching as the outstanding attractions, but skeptics, believers, and good croquet players are harder to come by today; Dr. Montague was forced to engage assistants. Perhaps the leisurely ways of Victorian life lent themselves more agreeably to the devices of psychic investigation, or perhaps the painstaking documentation of phenomena has largely gone out as a means of determining actuality; at any rate, Dr. Montague had not only to engage assistants but to search for them.

Because he thought of himself as careful and conscientious, he spent considerable time looking for his assistants. He combed the records of the psychic societies, the back files of sensational newspapers, the reports of parapsychologists, and assembled a list of names of people who had, in one way or another, at one time or another, no matter how briefly or dubiously, been involved in abnormal events. From his list he first eliminated the names of people who were dead. When he had then crossed off the names of those who seemed to him publicity- seekers, of subnormal intelligence, or unsuitable because of a clear tendency to take the center of the stage, he had a list of perhaps a dozen names. Each of these people, then, received a letter from Dr. Montague extending an invitation to spend all or part of a summer at a comfortable country house, old, but perfectly equipped with plumbing, electricity, central heating, and clean mattresses. The purpose of their stay, the letters stated clearly, was to observe and explore the various unsavory stories which had been circulated about the house for most of its eighty years of existence. Dr. Montague’s letters did not say openly that Hill House was haunted, because Dr. Montague was a man of science and until he had actually experienced a psychic manifestation in Hill House he would not trust his luck too far. Consequently his letters had a certain ambiguous dignity calculated to catch at the imagination of a very special sort of reader. To his dozen letters, Dr. Montague had four replies, the other eight or so candidates having presumably moved and left no forwarding address, or possibly having lost interest in the supernormal, or even, perhaps, never having existed at all. To the four who replied, Dr. Montague wrote again, naming a specific day when the house would be officially regarded as ready for occupancy, and enclosing detailed directions for reaching it, since, as he was forced to explain, information about finding the house was extremely difficult to get, particularly from the rural community which surrounded it. On the day before he was to leave for Hill House, Dr. Montague was persuaded to take into his select company a representative of the family who owned the house, and a telegram arrived from one of his candidates, backing out with a clearly manufactured excuse. Another

never came or wrote, perhaps because of some pressing personal problem which had intervened. The other two came.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.