FOREWORD

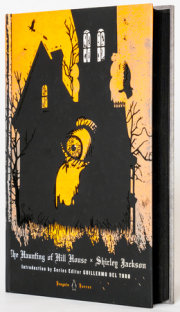

Shirley Jackson was, and continues to be, one of my greatest influences, a writer who suggested a way to engage with the strangeness of the larger world and yet stay true to whatever complicated ideas I wanted to express. I first read “The Lottery” when I was a preteen, still one of the most transformative reading experiences of my life, which led me to Hangsaman and The Haunting of Hill House, then her earlier works, as I searched for every written word that Jackson created, and ended when I finally read, long overdue, We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Jackson has remained the writer I look to when I want to understand the darkness of the world and how human beings internalize that darkness or, perhaps even more terrifying, create it themselves. The larger world has always been difficult for me to process, a constant source of anxiety, and Jackson’s work gave me a blueprint for how I might navigate that world without succumbing to paranoia; her stories were cautionary tales in which I somehow lived comfortably. The Bird’s Nest, though written early in her career, showcases what I find so engaging about Jackson’s work: her ability to create situations of quiet chaos that, no matter how much the reader seeks to find a tangible explanation, defy our attempts to categorize or fully understand it. The world, I understood through Jackson’s novels, could never be fully explained, and it was in those mysterious places that resisted definition that offered the most interesting stories.

• • •

The Bird’s Nest opens on a building in need of repair, a museum that features an “odd, and disturbingly apparent, list to the west.” When I reread this novel, the image immediately reminded me of Jackson’s exceptional later novels, We Have Always Lived in the Castle and The Haunting of Hill House, where the reader encounters ominous structures, domiciles that house strange and fascinating characters. A few pages into the story, we meet our main character, Elizabeth Richmond, a quiet, lonely young woman mourning the recent death of her mother, and we learn the possibility that “Elizabeth’s personal equilibrium was set off balance by the slant of the office floor” of the museum, where she works in the clerical department. Elizabeth’s office is on the highest floor of the museum and now, thanks to the renovation project, offers an open hole in the wall next to her desk that exposes “the innermost skeleton of the building” and induces the temptation to “hurl herself downward into the primeval sands upon which the museum presumably stood.”

For those of us who love Jackson’s work, this is familiar territory, and we are prepared for the listing structure to slowly drive Miss Richmond mad. Darkness enters the narrative when we learn that she is receiving threatening letters that exacerbate her recurring headaches and back pain. All of the elements are now in place and then, a testament to Jackson’s genius and a reason why The Bird’s Nest remains one of my favorite novels, Jackson shifts the narrative into a new and altogether more interesting direction. Elizabeth Richmond possesses multiple personalities, one of which leads her to sneak out of the house she shares with her aunt and into all manner of unsavory activities. The threatening letters have no source other than Elizabeth’s own hand. She admits to being unaware of these terrible events, but she can’t be sure. We now see that the structure housing strange and fascinating characters is not the museum but, rather, Elizabeth’s own body. And thus we discover the true focus of Jackson’s genius: the mysterious contents within all of us, the self-destructive tendencies that threaten to ruin the structure that keeps them hidden from the rest of the world.

• • •

As we leave the museum behind and enter into the unique workings of Elizabeth’s mind, the story becomes an examination of mental illness, the darkness inside us that we struggle to understand and keep at bay. Like Constance in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Eleanor of The Haunting of Hill House, and Natalie of Hangsaman, Elizabeth is a fragile, isolated young woman, but Jackson experiments with voice by revealing each distinctive personality, each one broken in some unique way. While sections of the novel are given over to Elizabeth’s sometimes unwilling psychiatrist, Dr. Wright, and her aunt Morgen, who possesses her own secrets, my favorite passages focus on the difficult inner workings of the mind of Elizabeth, or whichever personality currently inhabits her form. Jackson has always written with such precision about the delicate nature of our psyches, and as someone who has struggled with mental illness for my entire adult life, I think that there are few writers who know the ways in which our minds betray us as well as she does. When Betsy, Elizabeth’s most problematic and difficult personality, sneaks away from the care of Dr. Wright and Aunt Morgen to run off to New York in search of the mother she believes is still alive, the novel becomes electric and disturbing; it is hard to tell exactly what is happening, as Betsy’s thought processes are jumbled, but the world becomes a dangerous place, every human interaction fraught with the possibility of violence, every landmark simply another space that remains unknown to Betsy. It is some of the most thrilling and terrifying writing found in any of Jackson’s work.

While the good doctor’s work with Elizabeth, especially his use of hypnosis to treat multiple personalities, might provide the occasional breakthrough, I don’t believe Jackson intends to suggest that he truly holds sway over the bottomless depths of Elizabeth’s own mysterious desires and behaviors. The doctor in fact has an edge of something ominous in his own manner, played nicely against his self-deprecating humor. His interior complications explain his horror when he is confronted with the true nature of Elizabeth’s darkness. The doctor is merely a lion tamer attempting to subdue the human psyche, and one can’t help inferring Jackson’s opinion on the lasting success of domesticating such a wild animal.

While the book ends with the suggestion of happiness, or at least temporary calm, there is no happy ending. The threat of the world around us and the even more potent threats inside us cannot offer much in the way of happiness. Elizabeth, whatever her fate, is a sympathetic character, entirely human in her desires and actions, however strange they might be. This explains why, much like The Bird’s Nest itself and, in fact, all of Jackson’s work, it is so unsettling to see the darkness and chaos beneath the surface. We encounter a world where, thanks to Jackson’s talent, we recoil from the danger and then move closer to see it more clearly.

KEVIN WILSON

1

ELIZABETH

Although the museum was well known to be a seat of enormous learning, its foundations had begun to sag. This produced in the building an odd, and disturbingly apparent, list to the west, and in the daughters of the town, whose energetic borrowings had raised the funds to sustain the museum, infinite shame and a tendency to blame one another. It was at the same time a cause of much amusement among the museum personnel, whose several vocations were most immediately affected by the decided slant given to the floors of their building. The proprietor of the dinosaur was, as a matter of fact, very humorous about the almost foetal tilt of his august bones, and the numismatist, whose specimens tended to slide together and jar one another, was heard to remark—almost to tedium—upon the classical juxtapositions thus achieved. The stuffed bird man and the astronomer, whose lives were spent in any case almost out of earthly equilibrium, professed themselves unaffected by the drop of one side of the building, unless driven toward a kind of banking curve to offset the natural results of walking on tipped floors; walking was, in any case, an unfamiliar movement to either of them, one tending toward flight and the other toward the complacent whirling of the spheres. The very learned professor of archeology, going inattentively along the slanted corridors, had been seen hopefully contemplating the buckled foundations. The contractor and the architect, along with the ill-tempered daughters of the town, endeavored to blame first the inefficient materials supplied for the building and second the extraordinary weight of some of the antiquities contained therein; the local paper printed an editorial criticizing the museum authorities for allowing a meteor and a mineral collection and an entire arsenal from the Civil War, dug up just outside of town and including two cannon, to be lodged all on the west side of the building; the editorial pointed out soberly that, had the exhibit of famous signatures, and of local costume through the ages, been settled on the west side, the building might not have sagged, or might at least not have done so during the lifetimes of its sponsors. Since the local paper—current and impermanent—was not permitted below the third, or clerical, floor of the museum, the exhibits were allowed to retain their impractical arrangements unmoved by the editorials, although the clerical employees on the third floor read the comics daily and studied the front pages hoping to discover the manners of their deaths. They were given, on the third floor, to meditation, and they believed almost everything they read. In this, of course, they differed in almost no way from the educated inhabitants of the first and second floors who dwelt among unperishing remnants of the past, and made little wry jokes about disintegration.

• • •

Elizabeth Richmond had a corner of an office on the third floor; it was the section of the museum closest, as it were, to the surface, that section where correspondence with the large world outside was carried on freely, where least shelter was offered to cringing scholarly souls. At Elizabeth’s desk on the highest floor of the building, in the most western corner of the office, she sat daily answering letters offering the museum collections of pressed flowers, or old sea-chests brought back from Cathay. It is not proven that Elizabeth’s personal equilibrium was set off balance by the slant of the office floor, nor could it be proven that it was Elizabeth who pushed the building off its foundations, but it is undeniable that they began to slip at about the same time.

The instinctive thought of every person connected with the museum, up to and including the paleontologist, had been to repair, to patch together, to reconstruct, rather than to build anew in a new site, and in order to repair the building at all the carpenters had found it necessary to drive a hole the height of the building, from the roof to the cellar, and had chosen Elizabeth’s corner of the third floor to effect an entrance to their shaft. On the second floor the hole in the wall was discovered through a sarcophagus, and on the first floor, not unreasonably, behind a little door marked “Do not enter”; Elizabeth’s office allowed of no concealment, and so she came to work of a Monday morning to find that directly to the left of her desk, and within reaching distance of her left elbow as she typed, the wall had been taken away and the innermost skeleton of the building exposed. She was the first person in the room that morning; she hung her coat and hat neatly on the coat hanger just inside the door, and then went across the room and looked down with a swift sense of dizziness and an almost irresistible temptation to hurl herself downward into the primeval sands upon which the museum presumably stood; far below her she could hear the faintly echoing voices of the guides on the first floor; today was an Open Day and the guides were apparently cleaning their fingernails. The complaining voice which, slightly louder, seemed to come from the second floor may have been that of the archeologist, outside the tomb, finding fault with the air. Elizabeth, looking down, sighed because she had a headache, and because she had a headache nearly all the time, and turned to her desk to contemplate a letter offering the museum a model skyscraper made of matchsticks. The faint sense of holiday, inspired by not having a fourth wall to her office, had faded almost entirely by the time she opened the third letter on her desk. When she had read the letter once, she got up and looked down again into the cavity of the building, and then returned to her desk and sat down, thinking, I have a headache.

“dear lizzie,” the letter read, “your fools paradise is gone now for good watch out for me lizzie watch out for me and dont do anything bad because i am going to catch you and you will be sorry and dont think i wont know lizzie because i do—dirty thoughts lizzie dirty lizzie”

• • •

Elizabeth Richmond was twenty-three years old. She had no friends, no parents, no associates, and no plans beyond that of enduring the necessary interval before her departure with as little pain as possible. Since the death of her mother four years before, Elizabeth had spoken intimately to no person, and the aunt with whom she lived required little of her beyond a portion of her weekly pay and her prompt presence at the dinner table. Although she had arrived daily at the museum for two years, since her employment the museum had been in no way different; the letters signed “per er” and the endless listings of exhibits vouched for by E. Richmond were the outstanding traces of her presence. There were half a dozen people who spent their time in the same office, and half a dozen others who occupied other offices on the third floor, and all of these knew Elizabeth, and said “Good morning” to her, and even “How are you today?”—this on particularly bright spring mornings—but those of them who, in philanthropy or mortal kindness, had endeavored to become more friendly with her had found her blank and unrecognizing. She was not even interesting enough to distinguish with a nickname; where the living, engrossed daily with the fragments and soiled trivia of the disagreeable past, or the vacancies of space, kept a precarious hold on individuality and identity, Elizabeth remained nameless; she was called Elizabeth or Miss Richmond because that was the name she had given when she came, and perhaps if she had fallen down the hole in the building she might have been missed because the museum tag reading Miss Elizabeth Richmond, anonymous gift, value undetermined, was left without a corresponding object.

She had not chosen employment at the museum because of a passionate fondness for learning, or in the hope of someday managing a public institution of her own, but because in her usual undirected way she had followed the information given by a friend of her aunt’s, and found a job at the museum open, and because her aunt had added, most pressingly, that Elizabeth might very well try it, since it was necessary for Elizabeth to work at something now that she was old enough to be self-supporting. Her aunt forbore to comment upon her own uneasy sense that it might be easier to identify Elizabeth in some firmer manner if Elizabeth were located in a concrete spot (my niece Elizabeth, who works at the museum) rather than being merely herself and so very obviously unable to account for it. She went to work, then, with no further direction than this crossing of two lines to determine a point, and was taken on at the museum because the clerical work on the third floor required no very sparkling personality, and because her abilities, whatever her disadvantages, included a clear written hand and a moderate speed at the typewriter, and because whatever was given Elizabeth to do, if she understood it, was done. If she took any pride in anything, it was in the fact that everything about her was neat, and distinct, and right in a spot where she could see it. Her desk and her letters were squarely arranged; she came to the museum each morning at the hour she had been told to come, taking always the same bus to work and hanging up her coat and hat where they belonged; she wore always the dark dresses and small white collars which her aunt assumed were proper for an office worker, and when it came time to go home Elizabeth went home.

No one at the museum had stopped to think that driving an enormous hole through one side of Elizabeth’s office might be unhealthy for Elizabeth; no one at the museum had mused, slide rule in hand, “Now, let’s see, this shaft down the building ought to pass somewhere close to Miss Richmond’s left elbow; will it, I wonder, trouble Miss Richmond to find one wall gone?”

• • •

On Monday, just before noon, Elizabeth took her letter out of the drawer of her desk and put it into her pocketbook; she meant to read it again at lunch. It had nagged her during the morning, with an odd urgency; it was somehow most pleasantly personal, and not at all the sort of thing she was used to. Over her sandwich in the drugstore she read it again, investigating the handwriting, and the paper, and the wording; the most exciting thing about it was probably its lingering familiarity. It did not distress her because she could not conceive of someone imagining it, and taking a pen and a sheet of paper and writing it, and putting it into an envelope addressed to Elizabeth at the museum; it was an act of intimacy from a stranger impossible to picture. Sitting in the drugstore Elizabeth touched the badly written words with her finger and smiled; she had very definite plans for this letter: she meant to take it home and put it into a box on the top shelf of her closet with another letter.

Although the museum people spent the greater part of their own time in hammering and measuring and patching, it was generally felt that the presence of carpenters and bricklayers repairing the building was out of place during museum hours, and so as Elizabeth left the building as usual at four o’clock, she met the carpenters coming in. It was of no importance to anyone at the museum, and of little significance to the carpenters, but as Elizabeth passed them in the hallway she smiled and said to them, “Hello, there.” She went into the street, blinking in the sunlight because she still had her headache, stepped onto the usual bus, sat looking out of the window until she reached her own stop, stepped down from the bus, and walked the half block to her aunt’s house. She unlocked the door with her key, glanced at the hall table to see if her aunt had left any message, and into the living room to see if her aunt had got home, then went upstairs to her own room, where she hung her hat and coat carefully in the closet, took off her good shoes and put on sensible slippers, got a chair to stand on to reach the closet shelf, and took down the red cardboard valentine box which had held chocolates on her twelfth birthday. She carefully set the box down on her bed, put the chair back where it belonged, and sat down on the bed with the box. Before she opened it she took the new letter out of her pocketbook and read it again, then folded it and slipped it back into its envelope, addressed so untidily to miss elizabeth richmond, owenstown museum. Then she opened the box and took out the other letter inside; this one was substantially older. It had been written seven years before by Elizabeth’s mother and it read, “Robin, don’t write again, caught my Betsy at the letters yesterday, she’s a devil and you know how smart! Will write when I can and see you Sat. if possible. Hastily, L.”

Elizabeth had found this letter, presumably never addressed and mailed, in her mother’s desk shortly after her mother’s death. Until now it had been hidden alone on the closet shelf, but today, after reading both letters again carefully, she put both into the valentine box and, taking the chair, put the box back again onto the closet shelf, set back the chair, and went into the bathroom and washed her hands with soap as her aunt came to the foot of the stairs and called “Elizabeth? You home yet?”

“I’m here,” Elizabeth said.

“You want cocoa for dinner? It’s turned cold out.”

“All right. I’ll be right down.”

She came slowly down the stairs, kissed her aunt on the cheek because she usually kissed her aunt when she came home and she had not seen her aunt until now, and went into the kitchen.

“Well,” said Aunt Morgen definitely. She sat down heavily at the kitchen table, and folded her hands before her on the table, steadfastly disregarding the chops and the bread and butter. “Now,” she said. Elizabeth sat down hastily, and folded her own hands, and looked without expectancy at her aunt. “Lord, bless this food, our lives to Thy service,” said Aunt Morgen, speaking the moment Elizabeth folded her hands and seeming with an “Amen” in one pure gesture to unclasp her own hands and reach for the chops, “have you had a pleasant day?”

“Same as usual,” Elizabeth said. Food of any kind, under any circumstances, was a matter of substantial importance to Aunt Morgen, and her greed was only very slightly frosted over with conversation; there were, at best, only one or two topics in the world which could lift Aunt Morgen’s eyes away from her plate, and Elizabeth had never succeeded in saying anything which could surprise Aunt Morgen into putting down her fork before the food was gone. Dinner was calculated exquisitely to Aunt Morgen’s appetite, but she was fair; there were precisely as many chops and baked potatoes and slices of bread and pickles set out in Elizabeth’s name as were calculated for Aunt Morgen; their conversation was divided as perfectly.

“Have you had a pleasant day?” Elizabeth asked Aunt Morgen.

“Not very,” Aunt Morgen said. “Rained,” she pointed out.

Although Aunt Morgen was the type of woman freely described as “masculine,” if she had been a man she would have cut a very poor figure indeed. If she had been a man she would have been middle-sized, weak-jawed, shifty-eyed, and clumsy; fortunately, having been born not a man, she had turned out a woman, and had of necessity adopted from adolescence (with what grief, perhaps, and frantic railings against the iniquities of fate, which made her sister lovely) the personality of the gruff, loud-voiced woman so invariably described as “masculine.” Her manner was free, her voice loud, she loved eating and drinking and said she loved men; she took toward her sober niece an attitude of avuncular heartiness, and among her few friends she was regarded as fairly dashing because of her fondness for blunt truths and her comprehensive statements about baseball. She had reached an age where sustaining this character was no longer quite such a strain as it might have been when she was, say, twenty, and had reached a position of comparative complacence, discovering how the pretty girls of her youth had by now become colorless and dismal, and sometimes blushed when she spoke. She had never once regretted taking her niece in charge after her sister’s death, since in addition to being plain, Elizabeth was quiet and unobtrusive, and showed no inclination to interrupt her aunt’s conversation, which took place exclusively between the times of dinner’s conclusion and their hour of retirement. In the mornings, before Elizabeth left for the museum, Aunt Morgen frequently inquired after her health, and occasionally advised her to wear overshoes; before dinner, in a peaceful hour which Aunt Morgen spent making dinner and drinking sherry by herself in the kitchen and Elizabeth spent, as today, in her room, conversation was impossible; while dinner was being served and while it was being eaten, Aunt Morgen was too much occupied to speak. After dinner, however, Aunt Morgen habitually took a small glass or two, or even several, of brandy, and it was then, lounging back in her kitchen armchair, with coffee, brandy, and a cigarette on the table before her, and Elizabeth hesitating over her cooling cocoa, that Aunt Morgen held forth for the day.

“If you’d learn to drink coffee,” she began tonight, as she frequently did, “I’d let you have some of my brandy.”

“I don’t care for any, thank you,” Elizabeth said. “It makes me sick.”

“That’s because you drink it with cocoa,” Aunt Morgen said. She shuddered. “Cocoa,” she said. “Cocoa. Damn miserable puny stuff, fit for kittens and unwashed boys. Did Shakespeare drink cocoa?”

“I don’t know,” Elizabeth said.

“You ought to know things like that, you work in a museum. Me, I sit home all day on my fanny, living on my income.” She smiled and bowed formally to Elizabeth. “Your mother’s income, I should have said. Mine only by the merest faint chance, mine only because of deserving patience and superior intelligence. Mine,” said Aunt Morgen with relish, “only because I outlived her. If I had killed her, mind you,” she went on, pointing her cigarette at Elizabeth, “they would have caught me. I wouldn’t have gotten her money, because they would have caught me if I had killed her, and don’t think I didn’t think of it often enough, but they would have caught me. I don’t after all suppose that I’m that smart, kiddo.”

Aunt Morgen very often called Elizabeth “kiddo” after dinner, and she talked so much of Elizabeth’s mother when they were alone that Elizabeth, who had listened sometimes at first, found that she was now able to slip into a placid unlistening after-dinner state, almost as though she had taken a great deal of Aunt Morgen’s brandy. As Aunt Morgen’s voice went on, Elizabeth watched without awareness the changing lights on the silverware and the mirror over the sideboard, and the quick shadowy motion as Aunt Morgen lifted her brandy glass, and the endless pattern of rose-edged doorways on the wallpaper.

“—saw me first,” Aunt Morgen was saying, “but of course then your mother, once he met my sister Elizabeth, then it was her of course, and of course there was nothing I could do. But I flatter myself, Elizabeth junior, I flatter myself, that my intelligence and strength showed him finally what a mistake he made, choosing vacuity and prettiness. Vacuity,” Aunt Morgen said, enjoying the word, although she used it almost nightly. “Toward the end, I noticed, he came to me more and more, asking my advice about the money, and telling me his problems. I knew about the other men, but of course he had made his choice, although I must say she wasn’t so much by then, was she, up to her neck in mud. Well.” Aunt Morgen breathed deeply, leaning back, her eyes half-closed and regarding the brandy bottle. “Stack the dishes, kiddo? Early bed for Auntie.”

“I’ll wash them. Mrs. Martin comes to clean tomorrow and she gets mad if she finds dirty dishes.”

“Old fool,” said Aunt Morgen obscurely. “You’re a good girl, Elizabeth. No fancy notions.”

Elizabeth took the dishes to the sink and turned on the water; because she had begun to recognize, from her headache all day and the first beginnings now of an intolerable stiffness in her back—as though stretching, or rubbing against a doorway like a cat, would relieve her—that she was in danger of another attack of what Aunt Morgen called migraine and what Elizabeth thought of as a “bad” time, she moved deliberately and slowly, taking as long as possible over small motions; activity of any kind helped when she felt “bad.” These spells she remembered as from childhood, although Aunt Morgen believed that until the time of her mother’s death Elizabeth had only had temper tantrums, and remarked wisely that Elizabeth’s migraine was a “reaction of some kind.” In any case, the “bad” times had come with increasing frequency of late, and Elizabeth, recalling that she had been away from her work for four days not two weeks ago, thought dully, against the pain, “They’ll let me go if I keep staying home sick.”

By the time she had finished slowly washing and drying the dishes, and putting them carefully away on the shelves, and scrubbing the frying pan and scouring the sink and washing the table, the pain in her back was considerable; no longer a warning, it was now substantial enough for her to come to the door of the living room, where Aunt Morgen sat doing the crossword puzzle in the evening paper, and ask for an aspirin.

“Migraine again?” said Aunt Morgen, looking up. “You ought to run in and see Harold Ryan, kiddo.”

“I’ve always had it,” Elizabeth said. “Doctor Ryan couldn’t do anything.”

“I’ll get you a hot water bottle for that back,” Aunt Morgen said good-naturedly, setting down her pencil, “and one of those little blue pills. That’ll put you right to sleep.”

“I can sleep all right,” Elizabeth said. She was already dizzy, and reached out for the door frame.

“Poor baby,” said Aunt Morgen. “All you need is sleep.”

“Me?”

“Night after night I hear you tossing and muttering,” Aunt Morgen said. She put an arm around Elizabeth. “Come along, old lady.”

She helped Elizabeth undress, because the backache, which came with suddenness and severity, and disappeared again without warning, was by now severe enough to make it difficult for Elizabeth to move.

“Poor baby,” Aunt Morgen said over and over, taking off Elizabeth’s clothes, “many’s the time I undressed your mother before you were born. She,” said Aunt Morgen, chuckling, “was so clumsy then that when you got her on one side she couldn’t roll over without help. There you are, now the nightgown. Those last couple months were the only time she ever let anyone help her, anyone female, that is, and even then only me. Always private, she was. I must say, you didn’t get her body; more like your father, you are. Other arm, kiddo. She was a lovely girl, my sister Elizabeth, but mud clear up to the neck. Now for the hot water bottle and that nice little sleeping pill.”

“I’m almost asleep now, Aunt Morgen.”

“Not going to have you tossing all night tonight.”

When Aunt Morgen, walking very softly but stumbling over the night table, had finally turned off the light and gone away, Elizabeth lay in the darkness alone and tried to close her eyes. There was a line of light where Aunt Morgen had left the door a little open—it had not occurred to her that Elizabeth might need her in the night, but she was unable to remember to close a door completely—and Elizabeth could hear, from downstairs, Aunt Morgen’s easy movements, from the living room to the kitchen, and the subsequent slam of the refrigerator door, and Aunt Morgen’s voice humming to herself, in a kind of pride that she was well, and had outlived so many people.

Bad old woman, Elizabeth thought, and then was surprised at herself; Aunt Morgen had been very kind to her. “Bad old woman,” and she realized that she had spoken it aloud. Suppose she hears me, Elizabeth thought, and giggled. “Bad old woman,” she said, very loudly indeed.

“Did you call me, kiddo?”

“No, thank you, Aunt Morgen.”

Lying softly in her bed, the pain in her back lessening and the headache fading in the darkness, Elizabeth sang, wordlessly and almost without sound, to herself. The tune she used was of nursery rhymes, of faded popular songs, of whispers and fragments of tune she had heard long ago, and, singing, she fell asleep. She did not hear Aunt Morgen pass down the hall, nor perceive Aunt Morgen’s belated conscientious glance in through her doorway; she did not hear Aunt Morgen whisper, “You all right, kiddo?”

• • •

Aunt Morgen slept soundly of a night and awoke, ordinarily, ill-humored; it did not, therefore, surprise Elizabeth to awaken to Aunt Morgen’s displeasure. Elizabeth had lain quietly in bed for perhaps ten minutes, knowing from experience that, once awake, she would not fall asleep again, and, testing delicately, had decided that although she still had her backache, it was so much improved by a good night’s rest that she might certainly get up and go to work. The headache still pulsed somewhere at the back of her head, and she repeated what was—although she was not aware of it—an habitual gesture, that of rubbing her hand violently against the back of her neck, as though she might possibly rub the nerves there into submission, and anesthetize them against the pain; this habit was one of several persistent nervous gestures she used, and it did her headache no good whatsoever. When she came downstairs, dressed as neatly as usual, she came into the kitchen where Aunt Morgen, still in her bathrobe, sat sullenly at the kitchen table drinking her coffee. Elizabeth said “Good morning,” and went to the refrigerator for milk. When she sat down at the table opposite Aunt Morgen she said “Good morning, Aunt,” and still received no answer; when she looked up she realized that Aunt Morgen was regarding her angrily and without the ordinarily misty look of early morning. “My headache is better,” Elizabeth said timidly.

“So I see,” said Aunt Morgen. She tapped ominously on the edge of her coffee cup and prepared her face, by turning down the corners of her mouth and narrowing her eyes, for heavy irony. “I am happy,” she said deeply, “to know that your health was so much improved that you were able to leave your bed.”

“I thought I would go to work; I—”

“I was not referring,” said Aunt Morgen, “to your present state. The improvement in your health to which I refer took place, I should say, at approximately one o’clock this morning.” She stopped to light a cigarette, her hand shaking noticeably with fury. “When you decided to go out,” she finished.

“But I didn’t go out anywhere, Aunt Morgen. I slept all night.”

“Do you really suppose,” Aunt Morgen said, “that I am unaware of what goes on in my own house? Do you really suppose, you overgrown baby, that I am going to be taken in by your pretense of being sick and be sympathetic and bring you hot water bottles and give you pills and come to see how you are and put you to bed and be as nice as I can, and then for all my pains get laughed at? Do you really suppose,” Aunt Morgen went on, her voice rising intolerably, “that I don’t know what you’re doing?”

Elizabeth stared, speechless; childish defenses came back to her, and she dropped her eyes and looked at her glass of milk, and twisted her fingers together, and trembled her lip, and stayed quiet.

“Well?” Aunt Morgen leaned back. “Well?”

“I don’t know,” Elizabeth said.

“You don’t know what?” Aunt Morgen’s voice, softer for a moment, rose again. “What don’t you know, fool?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“I mean what’s going on in my house, I mean what you’re doing, I mean whatever dirty horrible nasty business you do in the middle of the night that even your own aunt can’t know about and you have to sneak out like a dirty thief, going down the stairs with your shoes in your hand—”

“I didn’t.”

“You did. And I will not be lied to. Now,” said Aunt Morgen, rising and leaning terribly across the table, “I mean to hear, before you leave this house today, exactly what you think you’re getting away with. And the sooner,” said Aunt Morgen, “the better.”

“I didn’t.”

“It won’t do you any good. Where did you go?”

“I didn’t go anywhere.”

“Did you walk? Or was someone waiting for you?”

“I didn’t.”

“Who? Who was waiting to meet you?”

“No one. I didn’t do anything.”

“Who was he?” Aunt Morgen slammed her hand down onto the table so that Elizabeth’s glass of milk rocked and spilled; the milk ran to the edge of the table and dripped onto the floor, and Elizabeth was afraid to move to find a cloth to wipe it up; she was afraid to do anything more than sit, avoiding Aunt Morgen’s eyes and twisting her hands under the table. “Who?” Aunt Morgen demanded.

“No one.”

Aunt Morgen opened her mouth, gasped, and took hold of the edge of the table with both hands. She closed her eyes tightly, shut her mouth, and stood, visibly calming herself.

After a minute she opened her eyes and sat down, and spoke quietly. “Elizabeth,” she said, “I didn’t want to frighten you. I’m sorry I lost my temper. I realize that by yelling at you I’m doing more harm than good; suppose I try to explain.”

“All right,” Elizabeth said. She looked quickly at the milk, and it was still running off onto the floor.

“Look,” Aunt Morgen said persuasively, “you know that as your only guardian I feel a great deal of responsibility. After all,” she said with a friendly grin, “I was your age once, much as I hate to admit it, and I can remember how hard it is to feel that people are keeping an eye on you. You feel independent, and free, and sort of as though you don’t have to account to anybody for what you do. But please try to realize, kiddo, that as far as I’m concerned, you can go ahead and do whatever you please. I’m not a dragon, or one of your fidgety old maids who faints when she sees a man. I’m your same crazy aunt, and I may be an old maid but I bet there’s not much left can make me faint.” Aunt Morgen hesitated and then, obviously resisting a train of thought which threatened to carry her away, went on firmly, “What I’m trying to say is, you don’t need to sneak in and out, and be afraid of my finding out something you’re ashamed of. If there’s some fellow you want to see, and you think for some reason I might mind your seeing him, don’t you think you’d be smarter to have me mad at you for seeing him—which I certainly couldn’t do anything about—than to have me mad at you for sneaking around and hiding things behind my back—which I certainly can do something about, and you just watch me—and all things considered, doesn’t it seem as though you’d be better off out in the open?” Aunt Morgen ran out of breath, and stopped.

“I guess so,” Elizabeth said.

“Then, look, kiddo,” Aunt Morgen said gently, “suppose you just tell auntie what it’s all about. Believe me, nothing is going to happen to you. You’ve got a right to do what you please, and remember, I’m not going to scold you, because I always did what I pleased, and I can remember perfectly well how you feel.”

“But I didn’t,” Elizabeth said. “I mean, I didn’t do anything.”

“Suppose you didn’t do anything,” Aunt Morgen said reasonably, “that’s still no reason for not telling me, is it?” She laughed. “It’s if you did do something you ought to be scared,” she said.

“But I mean I didn’t do anything.”

“Then what did you do?” Aunt Morgen asked. “What on earth can you find to do at that hour of the night if you didn’t do anything?” She laughed again, and shook her head, bewildered. “What a hell of a way to talk,” she said. “Don’t you know any honest words?”

“No.” Elizabeth thought. “I mean,” she said, “I didn’t do anything.”

“Good lord,” Aunt Morgen said. “Good holy lord God almighty, I can’t say it again. Are there any words,” she asked delicately, “which might communicate with your dainty brain? I am trying to ask you precisely what occurred, and with whom, at one o’clock last night.”

“Nothing,” said Elizabeth, twisting her hands.

“I am by now completely convinced that it was nothing,” said Aunt Morgen fervently. “I am only astonished that he could have expected anything else. There must be people,” she said as though to herself, “like that in the world, but how does she find them? Who, then,” she continued to Elizabeth, “was this optimistic young man?”

“No one,” said Elizabeth.

“Blood from a stone,” said Aunt Morgen, “gold from sea water, fire from snow. You’re your mother’s own daughter, mud up to the neck.” She laughed, unexpectedly good-humored. “I don’t know why,” she said, still laughing, “I should believe that you would go out on a cold night to meet a young man. My own private guess, being you’re your mother’s daughter, is that you’d make a big mystery of going out to mail a letter, and hope someone would think the worst of it. Or to find a nickel you lost last week. And if it is some fellow,” she added, pointing jeeringly at Elizabeth, “I’ll bet your poor dear father’s fortune he isn’t fooled. You’re like your mother, kiddo, a cheat and a liar, and neither of you could ever get around me.”

“But I didn’t,” Elizabeth said helplessly.

“Of course you didn’t,” Aunt Morgen said. “Poor baby.” She rose and left the kitchen, and Elizabeth was finally able to get the dishcloth and wipe up the spilled milk.

• • •

There was still a gaping hole in her room at the museum, and it stayed just beyond her left elbow all day. In the morning mail, which included a letter asking the museum for a complete listing of the exhibits in the Insect Room, and a letter asking for a final decision upon an unparalleled collection of Navajo hammered silver, there was another letter for Elizabeth. “ha ha ha,” it read, “i know all about you dirty dirty lizzie and you cant get away from me and i wont ever leave you or tell you who i am ha ha ha.”

Coming home that afternoon with the letter in her pocketbook Elizabeth stopped suddenly on the street between the bus stop and her aunt’s house. Someone, she thought distinctly, is writing letters to me.

She put this letter also into the red valentine box which had held chocolates on her twelfth birthday, and opened and reread the other two. “i will catch you . . .” “She’s all I have . . .” “you cant get away from me . . .”

“Well?” Aunt Morgen said after dinner. “You decided to give in?”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“You didn’t do anything,” Aunt Morgen said. “All right.” She looked coldly at Elizabeth. “You got another one of your phony backaches?”

“Yes. I mean, I have my backache again. And my head aches.”

“For all the sympathy you’ll get from me tonight,” Aunt Morgen said heavily. “How often you think you can get away with it?”

• • •

“And how is our poor head this morning?” Aunt Morgen inquired at breakfast.

“A little better, thank you,” said Elizabeth, and then she saw Aunt Morgen’s face. “I’m sorry,” she said involuntarily.

“Have a pleasant time?” Aunt Morgen asked. “Poor devil still hoping?”

“I don’t know—”

“You don’t know?” Aunt Morgen’s irony was heavy. “Surely, Elizabeth, even your mother—”

“I didn’t.”

“So you didn’t.” Aunt Morgen turned back to her coffee. “How do you feel?” she asked finally, grudgingly.

“About the same, Aunt Morgen. My back hurts, and my head.”

“You ought to see a doctor,” Aunt Morgen said, and then, standing abruptly, and slamming her hand on the table, “honest to God, kiddo, you ought to see a doctor!”

• • •

“. . . and i can do whatever i want and you cant do anything about it and i hate you dirty lizzie and youll be sorry you ever heard of me because now we both know youre a dirty dirty dirty . . .”

• • •

Elizabeth sat on her bed, counting her letters. Someone had written her lots of letters, she thought fondly, lots of letters; here were five. She kept them all in the red valentine box and every afternoon now, when she came home from work, she put the new one in and counted them over. The very feel of them was important, as though at last someone had found her out, someone close and dear, someone who wanted to watch her all the time; someone who writes letters to me, Elizabeth thought, touching the papers gently. The clock on the stair landing struck five, and reluctantly she began to gather the letters together, folding them neatly and putting them back into their envelopes. She would not like to have Aunt Morgen see her letters. They were all safely back in the box and she had put away the chair she stood on to put the box onto the shelf of her closet, when the door crashed open and Aunt Morgen came in. “Elizabeth,” she said, “kiddo, what’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” said Elizabeth.

Aunt Morgen’s face was white, and she held tight to the doorknob. “I’ve been calling you,” she said. “I’ve been knocking on your door and calling you and outdoors looking for you and calling you and you didn’t answer.” She stopped for a minute, holding tight to the doorknob. “I’ve been calling you,” she said at last.

“I’ve been right here. I was just getting ready for dinner.”

“I thought you were—” Aunt Morgen stopped. Elizabeth looked at her anxiously, and saw that she was staring at the table by the bed. Turning, Elizabeth saw one of Aunt Morgen’s brandy bottles on the table. “Why did you put that in my room?” Elizabeth asked.

Aunt Morgen let go of the doorknob and came toward Elizabeth. “God almighty,” she said, “you stink of the stuff.”

“I don’t.” Elizabeth backed away; Aunt Morgen, unreasonably, frightened her. “Aunt Morgen, please let’s go have dinner.”

“Mud.” Aunt Morgen took up the brandy bottle and held it to the light. “Dinner,” she said, and laughed shortly.

“Please, Aunt Morgen, come downstairs.”

“I,” said Aunt Morgen, “am going to my room.” Eyeing Elizabeth, she backed toward the door, the brandy bottle in her hand. “I think,” she said, her hand again on the doorknob, “that you are drunk.” And she slammed the door behind her.

Perplexed, Elizabeth went over to sit on the bed. Poor Aunt Morgen, she thought, I had her brandy. Absently, she noticed that the bedside clock said a quarter past twelve.

• • •

“. . . i know all about it i know all about it i know all about it dirty dirty lizzie dirty dirty lizzie i know all about it . . .”

• • •

Because the next day there was proof to correct on the museum catalogue, Elizabeth, with her new letter safely in her pocketbook, did not leave the building until quarter past four, when the workmen were already engaged on the hidden structure of the building. As a result, she missed her usual bus home. When she finally came into the kitchen where Aunt Morgen sat drinking her brandy, Elizabeth saw first that Aunt Morgen had not eaten any dinner, and then she looked up into her aunt’s hard stare. Wordless, Elizabeth could only hold out placatingly the box of chocolates she suddenly discovered she was carrying.

• • •

Mr. and Mrs. Arrow fancied themselves as homey folk in a circle where all their acquaintance collected Indian masks, or read plays together of an evening, or accompanied one another on the sackbut; Mr. and Mrs. Arrow served sherry, and played bridge, and attended lectures together, and even listened to the radio. Mrs. Arrow was accustomed to deplore as extreme Aunt Morgen’s habit of going to the movies alone, and both Mr. and Mrs. Arrow felt that Elizabeth was allowed too much freedom; Mrs. Arrow had said as much, indeed, to Aunt Morgen when Elizabeth first went to work at the museum. “You allow that girl too much leeway, Morgen,” Mrs. Arrow had said, making no bones about the way she felt, “a girl like Elizabeth takes more watching than one of your . . . one of those . . . that is to say, Elizabeth, you know as well as I do, takes watching. Not that Elizabeth’s not normal.” Mrs. Arrow had stopped and lifted her eyes to heaven and spread her hands innocently, so that no one would ever believe that Mrs. Arrow meant to imply for a minute that Elizabeth was anything apart from normal, “I don’t mean that at all,” Mrs. Arrow explained earnestly. “What I mean is, Elizabeth is an unusually sensitive girl, and if she is going to go off by herself every day for long periods of time, it would be most judicious, Morgen, most wise of you, to check carefully that she is always among people of the most genteel sort. Of course,” Mrs. Arrow went on, nodding reassuringly, “over at the museum they’re mostly volunteer workers. I always think,” she finished, “that it’s so kind of them.”

Mr. Arrow had at one decisive point of growth taken a set of singing lessons to improve his poise, and he was still very apt to sing when even very slightly invited to; Mr. Arrow customarily entertained guests with songs like “Give a Man a Horse He Can Ride,” and “The Road to Mandalay,” and Mrs. Arrow accompanied him on the piano, pedalling furiously and occasionally humming the easy parts; “For God’s sake,” Aunt Morgen said to Elizabeth, pressing her finger insistently upon the doorbell, “don’t ask Vergil to sing.”

“All right,” Elizabeth said.

“Ruth,” Aunt Morgen said, as the door opened, “how good to see you again.”

“How are you, how are you,” said Mrs. Arrow, and Mr. Arrow, behind her in the hall and smiling largely, said “How are you? And here is Elizabeth, too; how are you, my dear?”

Because the Arrows neither collected Indian masks nor patronized a decorator, they were forced to use ordinary pictures on their walls, and whenever Elizabeth thought of the Arrows’ home she remembered the bright reproductions of country gardens and placid smooth hills and sunsets; the Arrows also had an umbrella stand in their hallway, although both of them laughed about it and Mr. Arrow, in his faint deprecating way, said that after all it was the very best place to put wet umbrellas. When Elizabeth, coat neatly hung in the Arrows’ hall closet, sat in a great chair in the Arrows’ living room, with her hands folded correctly in her lap and Aunt Morgen spreading herself comfortably in just such another chair, and Mr. and Mrs. Arrow nervously together on the sofa, Elizabeth felt safe.

The whole room partook somehow of the smooth hills and sunsets; the chair in which Elizabeth sat was soft and deep and upholstered in a kind of cloudy orange, her feet lay on a carpet in which a scarlet key design ran in and out and around a geometric floral affair in green and brown, and the wallpaper, pervading and emphasizing the room, and somehow the Arrows, presented the inadvertent viewer with alternate squares of blue and green, relieved almost haphazardly by touches of black. There was nothing of harmony, nothing of humor, in the Arrows’ way of life; there was everything of compromise and yet, comfortably, a kind of deep security in the unmistakable realization that all of this belonged without dispute to the Arrows, was unmovable and after a while almost tolerable, and was, beyond everything else, solid. Not even Aunt Morgen could deny the Arrows the reality of their living room, and when one met them at a lecture on reincarnation, or walking placidly together toward the park on a Sunday afternoon, or dining at the home of one of those odd people who always seemed to invite them, Mr. and Mrs. Arrow brought with them, and spread infectiously, an air of unfading wallpaper and practical carpeting, of ironclad and frequently unendurable mediocrity.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.