I

AzcapotzalcoTime heals everything, except wounds. —Chris Marker, Sans Soleil

[here, under this branch, you can speak of love]

The tree is brimming with invisible birds. At first I think it must be an elm tree—it has the same sturdy and solitary trunk supporting the sprawling branches that I recognize from my childhood—but soon, just a couple days later, it is clear that it is an aspen, a foreign species transplanted long ago to this part of Mexico City, an area poor in native vegetation. We sit beneath it, right on the edge of a yellow curb. The sun slowly setting. Across the busy street and behind tall metal gates, gray factory towers stretch upward, and heavy power lines bend, barely horizontal, against the sky. Trailers drive by at great speed, as do taxis and cars. Bicycles. Of all the evening noises, the sound of birds is the most unexpected. I have the impression that if we move beyond the tree’s shadow we will not be able to hear them anymore. Here, under this branch, you can speak of love.// Beyond lies the law, the need, / the trail of force, the preserve of terror./ The fief of punishment. // Beyond here, no. But we listen to them and in some absurd, perhaps unreasonable, way their repetitive and insistent singing triggers a calm that cannot erase disbelief. Do you think she will come? I ask Sorais as she lights a cigarette. The lawyer? Yes, she. I have never known what to call that movement, when lips pressed together stretch toward one side of the face, dismissing any illusion of symmetry. I’m sure we’ll see her soon, she says in response, spitting out a strand of tobacco. In any case, it wouldn’t hurt to wait another half hour. Or another hour. Looking at her sideways, hesitantly, I have to admit to myself that I mentioned the lawyer because I wanted to avoid asking her to wait with me. Supplicate is the verb. I did not want to beg. I did not want to beg you to wait here with me for a little longer because I don’t know if I will be able to, Sorais. Because I don’t know what animal I am unleashing deep within. We are now six hours and twenty minutes into a journey that started at noon, in what now seems to have been another city, another geological era, another planet.

[twenty-nine years, three months, two days]

We’d agreed to meet at noon at the place where I was staying. An old house turned into a boutique hotel. A white fence flanked by bougainvillea and vines. An old gravel passageway. Palm trees. Rose bushes. And while I wait for Sorais with some anticipation, I don’t take my eyes off the city on the other side of the windows. It welcomes just about everyone, this city. It kills just about anyone too. Lavish and unhealthy at the same time, cumulative, overwhelming. Adjectives are never enough. When Sorais arrives at the house that is to be my home those few autumn days in Mexico City, I don’t know if I will be able to.

There are two things I must do today, I tell her right away as we hug and exchange greetings. The aroma of soap in her hair. The moisture of her skin after a hot bath. Her voice, which I have known for years. Well let’s go then, she answers immediately, without even asking for more details. It might take all day, I warn her. And it is then that she pauses, looking into my eyes. So where are we going? The intrigue in her voice betrays expectation, not suspicion. I am silent. Sometimes it takes a bit of silence for words to come together on the tip of the tongue and, once there, for them to jump, to take the unimaginable leap. This dive into unknown waters. To the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office, near the downtown district. She keeps quiet for a moment now, paying close attention. About two weeks ago, I tell her, on another trip to the capital city, I met up with John Gibler, the journalist who helped me start the process of finding my sister’s file. She looks down, and then I know for a fact that she knows. And understands. After a brief search in the newspaper archives, I continue, John found the news just as it was published in La Prensa twenty-nine years ago. He managed to contact Tomás Rojas Madrid, the journalist who wrote the four articles that documented the murder of a twenty-year-old architecture student in a surprisingly restrained tone, in language devoid of emotion or sensationalism, succinctly depicting the crime that had alarmed a neighborhood in Azcapotzalco on July 16, 1990. And I came, I continue explaining, to meet the two of them, the two journalists, at the Havana Café, that famed and crowded place, and walked with them to the building of the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office. Because I wanted to file a petition there, I tell her. How does one even formulate such a letter? Where does one learn the protocols for requesting a document of this nature?

October 3, 2019. Mexico City.

C. Ernestina Godoy Ramos. Attorney General of Mexico City.

My name is Cristina Rivera Garza, and I am writing to you as a relative of LILIANA RIVERA GARZA, who was murdered on July 16, 1990, in Mexico City (Calle Mimosas 658, Colonia Pasteros, Azcapotzalco Delegation). I am writing to request a full copy of the case file that at the time corresponded to Public Ministry record no. 40/913 / 990-07.

If you need more information, please do not hesitate to contact me at the following address.

Best regards.

There is only a slim chance of recovering the file, I clarify again, after all these years. Twenty-nine, I added, twenty-nine years and three months and two days. I am silent again. Things are so difficult sometimes. But they are supposed to have an answer for me today, I say.

[the younger sister]

We decide to walk. The journey, according to Google, would not take us more than forty-four minutes on foot. And the day is spectacular. So we trek forward. One step after another. A word. Many more. If it weren’t for the fact that we are pursuing the record of a murdered young woman, this could be mistaken for any random outing in a touristy city. Avenida Ámsterdam is a legendary street in La Condesa, a Porfirian neighborhood established in 1905 that still boasts its old art deco and art nouveau mansions, now sandwiched between apartment buildings with shiny windows and roof gardens. The neighborhood was also known as the Hippodrome because the avenue along which we walk this morning was, in its origins, the oval track where horses raced against each other. Desperately. It is easy to imagine them: the horseshoes against the loose dirt of the arena, the rattle of their gallop, their glistening skins, the upright manes. Their rosy gums. One after another, those horses. Running as if their life depended on it. Aren’t we all? The air from the past lingers, crisp and sharp, full of uproar, against our nostrils while the canopy overhead prevents sunlight from passing through. Still, Avenida Ámsterdam remains a must-see. Elongated and paved with bricks, the path is a closed form, a kind of physical villanelle that thwarts the experience of continuity or the feeling of finitude. You always go around, endlessly, inside an oval, after all. You are always a horse running against the past.

The muffled echoes of English or French or Portuguese pass us by, ringing quietly on the sidewalks. But a street vendor surrounded by the pungent aroma of wild marigolds on one of the banks of the Parque México speaks Spanish. And so does the paper collector, singing his old-time tune while dragging a metal cart ever so slowly: papeles viejos, periódicos usados que venda. The construction workers who have borne the weight of the renovations that turned this neighborhood into an oasis for hipsters and young professionals speak languages that come from far away in the highlands or from shanty neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city. If I lived in Mexico I could not afford a home here. But I’m passing through. I take advantage of a research visit at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) to trace the file for investigation 40/913 / 990-07, which contains the arrest warrant issued against Ángel González Ramos for the murder of Liliana Rivera Garza, my sister. My younger sister.

My only sister.

[already exhausted, already fed up, already forever enraged]

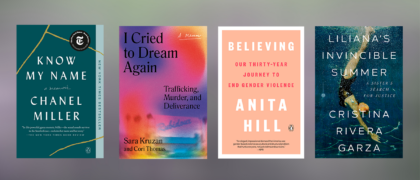

Copyright © 2023 by Cristina Rivera Garza. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.