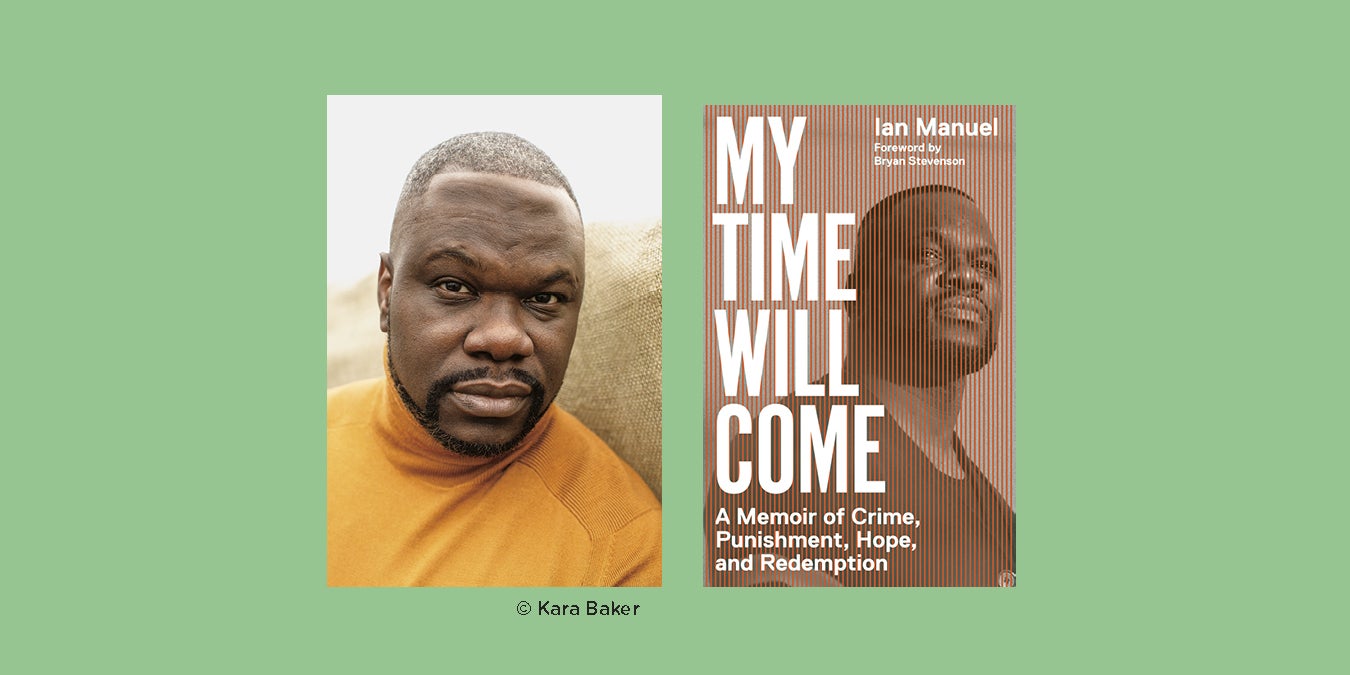

1.

My story has been told many times. you can read it in police files and court records, case notes and daily logs. The story of my birth, for example, told by a judge sentencing my mother to prison soon after my arrival in this world. And there’s the story of that day when I was five, in the case notes of a social worker who drove me to a foster home and then, a few days later, drove me back to the projects, to the room I had shared with my abuser. The story of my childhood was told multiple times by juvenile probation officers who found me to be a problem best managed inside the walls of institutions. In the illustrious space—cold and intensely bright in my memory—of an adult courtroom, it would be the robed and sober voice of a judge who would foretell my death when I was thirteen. Relying on the stories of police officers, lawyers, and other accomplished professionals, he would send me to Florida State Prison, never to be released. As I said, my story has been told many times and by highly regarded experts in their fields. But today, if you’ll bear with me, I would like to try to tell it to you myself. I have reason to believe the experts may be wrong about me. You see, today, thirty years later, I am neither in prison nor dead.

In the stories told of my life, each begins with a crime. A crime by my mother against a neighbor, crimes against me, crimes committed by me. My stories are defined by legal codes and diagnostic categories. To tell you the truth, I struggle to shake these, to describe myself to you as I am, in all that I am. My sense, though, is that this is an experience true to millions of people who, like me, happened to be born into poor neighborhoods at a time in history when the intervention of choice is arrest and incarceration—even for mothers of infants, even for young children. I would like not to begin my story as the experts have done, with the story of a crime. But that is, in fact, the reality of this life. So I will begin with the story of the worst thing I have ever done, the crime I was sentenced to die in prison for. But I begin here not because, as the experts have said, this defines me. I begin here because I hurt someone very badly during a time in my life when I was blinded by my own hurt. And I want to admit to it. I want to state the truth of it. I think I owe it to her. And to the child that I was. I think we need to speak about harm, what we’ve done, what’s been done to us, because that is what will open doors, what will air out and begin to heal the wounds we carry and have caused. And that is what will allow for new stories to begin to be told. I am telling you my story today because I want to tell a story of hope and meaning, of being one among a human family.

#

I shot Debbie Baigrie on July 27, 1990. I was thirteen and, along with a group of older boys, I was trying to rob her and the man who was walking her to her car. He, of course, was walking her to her car out of concern for her being a woman, alone at night, in a parking lot. My friends and I were the embodiment of his reasons for concern and I believe that night I only confirmed any beliefs he had about kids like me.

At the time, my mom and I were homeless, staying with a family friend in the housing projects I had called home most of my life. Central Park Village had been a prosperous, entrepreneurial black community before I was born. But after deadly riots and looting there in 1967, the neighborhood had fallen on hard times. It was now a complex of run-down, low-rise buildings, riddled with poverty, gang violence, drugs, and crime. Because Mom had let the rent on our place fall behind, she and I were staying with a lady known to me as Aunt Louise, though she was no relation of ours. During my childhood, Central Park Village was a place of comings and goings, among family, friends, and acquaintances; the place was full of people like us—roamers.

#

Guns were not new to me. When I was eleven, my friend Marquis and I had gone jacking, committing our first crimes together—robbing people, seventy-five cents here, two dollars there—only to be arrested. The gun we had brandished turned out to be an old, rusty, empty Colt M1911, the standard-issue sidearm of the U.S. Armed Forces from 1911 to 1986. Toward the end of that school year, during a conflict I had with a classmate, Marquis’s cousin had pulled the gun out, pointed it at my opponent, and insisted that I fight him. The gun I would end up using to shoot Debbie was a .32 revolver.

On the night of the crime, I met up with Marquis, who was fourteen at the time, and two older boys from the neighborhood and we walked downtown. Downtown Tampa was my stomping ground for a couple of years. I knew where police cars were stationed; where it was too crowded to pull off a robbery; where it would be unlikely for us to get caught.

We continued downtown, searching for the right place at the right time, but I was nervous.

Marquis was stern in a friendly way: “Man, Jim-Jim, look it done turned nighttime and we ain’t done nothing yet. The next people we come across, we jacking, whether it’s too open or not.” Everybody agreed. We didn’t have far to go before an opportunity presented itself: as we were walking across the parking lot, we turned to see a white man and woman, leaning against a car, rapt in conversation.

One of the boys cooked up a plan on the spot. “Jim-Jim, I’m gonna go over and ask ’em for some change. When you see one o’ dem reach for dey money, do your thing.” “All right,” I said. Marquis and the other boy stood right behind me. “Do one of y’all have change for a twenty?” the boy asked. I thought I heard either the man or the woman say yes. At the top of my lungs I yelled, “It’s a jack, y’all, give it up,” pointing the revolver at them. The woman stared at the gun and screamed, which startled me. Before I knew it I had pulled the trigger and she took off, running.

#

TAKE IT BACK

Her mouth opens as she inhales her scream. The bullets are reloaded because the trigger was never squeezed. We’re back at the start when we first asked for change. And her face is the same because she never felt that pain. He isn’t on his knees—looking me in my eyes. Like I’m the last thing he’ll see for the first and final time. The song self-destruction isn’t resounding in my mind. We’re just standing at the scene. Before it became a crime. If I could see into the future. Sitting on that porch on India. When my codefendants came to visit. I’d’ve chosen to stay with Lydia. I’m back in Central Park. Two-story apartment building. Never knowing where I’m going . . .

Copyright © 2021 by Ian Manuel. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.