Project Mauna A Wākea This is a story about land, culture, and connection to place—this is the story to protect Mauna a Wākea on the Big Island of Hawai‘i. Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian people) have been fighting to stop the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) since 2009, and in the summer of 2019, a resistance camp was established at Pu‘u Huluhulu. Kia‘i (protectors) slept in a parking lot over a lava field at the bottom of the access road to the summit of Mauna Kea for nearly a year to stop construction of what would be the largest telescope in the Northern Hemisphere.

Mauna Kea is a dormant volcano and is the tallest mountain on Earth from the seafloor to its summit. Its abbreviated name (which means “white mountain”) is short for Mauna a Wākea, the mountain of the Hawaiian deity Wākea. For Kānaka Maoli, it is considered the most sacred place, fundamental in their creation story and time-honored in their traditions. The destruction and ongoing desecration from tourism and the existing thirteen telescopes on Mauna Kea have been devastating to the mountain’s fragile and unique ecosystem and are blatantly disrespectful to Kānaka cultural beliefs.

Our All My Relations podcast team flew to Hawai‘i in January of 2020 to meet with the kūpuna (elders), activists, and scholars behind the movement. When we arrived, it was sunny and warm; the air smelledgood and it quenched our sun-thirsty, Pacific Northwest souls. But when we ascended the Mauna the weather changed. It was cold. The mist was thick. We arrived to Pu‘u Huluhulu to see kia‘i doing evening protocol in jackets and bare feet. I got this sudden, familiar feeling that I was in a sacred place, and that I needed to respectfully follow the protocol as a guest in this country (which is how we should all act when visiting Hawai‘i, since all non-Kānaka are guests there). While at Pu‘u Huluhulu, we were able to visit the kūpuna tent and talk story. There we met Dr. Noe Noe Wong-Wilson, a professor, educator, cultural practitioner and Native rights activist. We sat with Auntie Noe Noe in a minivan on the Mauna, as the rain poured down on us. She introduced us to the fundamental and powerful reason for the movement. “ ‘Āina, land, is an inseparable part of our identity as Hawaiians,” Auntie Noe Noe said. “And along with the land comes spirituality because these things, these inanimate things that cannot be produced by a human, are what we call the Gods. So, we revere the very rocks we walk on, the very rocks that you’re standing on. To see it abused in this way is painful to the soul. It’s painful to our Native soul. That’s why we stand.”

In our first moments on the Mauna, we were invited to participate in the evening protocol led by Lanakila Mangauil, a fierce Hawaiian cultural practitioner, hula teacher, and activist. “I am a strong advocate for the protection and cultivation of Hawaiian culture and the rights of Indigenous peoples as directly connected to the rights, protection, and restoration of the environment,” Lanakila told us. His passion fueled the movement to protect Mauna Kea—he led protests, engaged the public via social media, taught cultural classes, and even put his body on the frontline to stop construction. Because of his cultural knowledge and his loquacious nature, Lanakila elaborated on the significance of the Mauna.

“It was the first child born of Papahānaumoku and Wākea, which is the Earth Mother and the Sky Father. Then the siblings, the younger siblings of the islands themselves, continued to emerge forth. And eventually also the sibling who is HoʻohŌkūkalani the Star Mother, she is the next, who then birthed the Kanaka, the human, and was brought here to the Earth. And so, we see the mountain as the eldest of all of our siblings. As the hiapo, or the eldest child, it does all this work to gather the nutrients and to feed them to all of us younger siblings. And we maintain that relationship.

It’s also very sacred to us as being one of the highest points in all of Oceania. It is a burial ground, especially for our high chiefs, high priests, and particular families that are related to the deities of this mountain. For generations upon generations, the bones of ancestors are laid to rest on this mountain. It is a tradition of our people too that we don’t mark graves. They are hidden away. The fact that you look and you don’t see stone heads or markers doesn’t mean that they aren’t there. It is a tradition to hide the bones. So there is a burial ground to elevate our ancestors into the heavens.

It is also very symbolic for us because we see the mountain also as a piko, which is an umbilical. The mountain is the umbilical of this honua [planet] that stretches into oli ka lani, the black of space is the placenta. And the imagery of that is the mountain channels all this mana [spiritual life force] of the universe to come down through it and it shares it for the growing embryo which is this Earth.

”Lanakila paints a strong picture—the Mauna is the piko and the telescopes are cancers. In fact, Kānaka Maoli seldom summit the Mauna since it is a realm reserved for the Gods. The sacrality of the mountain is equally tied to its cultural, religious, and scientific environmental value, as Lanakila explained: “Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa are both registered ice mountains. Within the core of the mountains is permafrost and that’s what helps hold the lake up there and what also has been, from the Ice Age, what gives us these artesian wells that permeate down.” It’s

well known that the fresh water supply on the Big Island is dependent on the Mauna’s naturally occurring water cycle, in which the atmosphere, ocean, land, and sun are all working together to replenish the island’s fresh water.

The construction and presence of the telescopes have desecrated the mountain and blatantly disrespected what Kānaka Maoli hold dear. Environmental Impact Statements determined that prior construction sites were destructive to its ecosystem, and although Mauna Kea is legally classified as conservation land, it continues to be denied protection. Hawaiian development and the construction of the roads to access the existing telescopes has led to upward of a thousand tourists visiting Mauna Kea every day. Intrinsically tied to the movement to protect Mauna Kea is Kānaka Maoli sovereignty, nationhood, and identity—undermining and disrespecting the Mauna is equivalent to undermining and disrespecting the Kānaka Maoli. The movement to protect the sacred is just as Lanakila said: “Without the land, we have no culture. Our culture cannot exist without these places.”

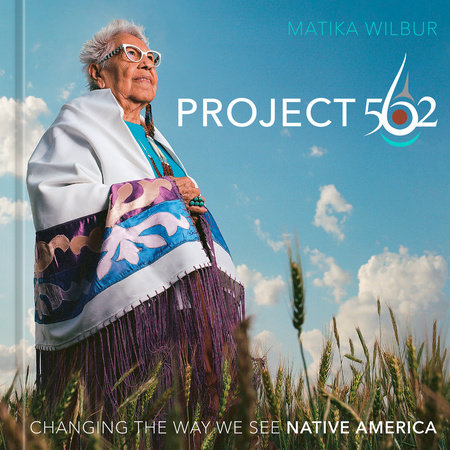

Copyright © 2023 by Matika Wilbur. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.