OneNovember 1938Hedy Wachenheimer cycled down Adolf-Hitler-Strasse on her way to school. It was a bitterly cold morning. The whitewashed two-story brick houses on either side of the road were shrouded in predawn gloom. Dim lights flickered behind the still drawn shutters.

When Hedy reached the edge of the village, near the sign reading JEWS ARE UNWANTED HERE, she dismounted. There was a steep incline ahead. Lacking the strength to pedal uphill, she pushed the bike into the open countryside.

The sun soon began to rise. Often at this time of year, in the late fall, a thick mist settled over the fields and vineyards of the upper Rhine valley, making it difficult to see more than a few feet ahead. But today the frosted meadows and trees sparkled in the early morning light. The road was slick from the fallen leaves of the aspens and birches that mingled with the firs and pines of the forest.

Shivering in the frigid air, Hedy thought about the strange behavior of her parents the previous evening. They seemed unusually nervous and preoccupied. Her father had told her to hide inside the wardrobe if woken by “loud noises” during the night. Her parents refused to explain the reason for their concern. This was unlike them. An only child, Hedy was accustomed to sharing their joys and sorrows.

The talk of trouble seemed connected somehow to a report, on the radio, that a German diplomat in Paris had been murdered by a crazed Jewish refugee. Why that had anything to do with the Wachenheimer family, living hundreds of miles away in Kippenheim, an obscure village in the Baden region of southwest Germany, the fourteen-year-old did not understand. In the end, Hedy and her parents had slept undisturbed.

It took Hedy roughly forty minutes to make the three-mile trek to school, half walking, half pedaling. With just eighteen hundred inhabitants, Kippenheim was not big enough to have its own high school, so Hedy was obliged to commute to nearby Ettenheim. The winding country road took her through the foothills of the Black Forest, beloved by generations of Germans for its picture-perfect villages, hiking trails, and gorgeous scenery. To her right was a castle, atop a hill, with a commanding view of the Rhine River. The mountains of eastern France formed a dark bluish blur in the distance, on the other side of the wide river plain.

Back in the seventeenth century, when Jews first settled in the area, the Mahlberg Schloss had been part of the defenses of the Holy Roman Empire. It had been built by the rulers of Baden, known by their aristocratic title of “margrave.” The margraves had relied on Jewish bankers and wealthy businessmen to provision their armies. These “court Jews” relied in turn on a network of rural Jewish traders willing to do business on more favorable terms than Christian merchants in big towns like Freiburg that were off-limits to Jews. Protected by the margraves, Jews had been living in the strategically important border region ever since.

Hidden in the hills on the opposite side of the road from the castle was the Jewish cemetery at Schmieheim, where three generations of Wachenheimers lay buried. It was a heritage that meant little to Hedy, who did not even know she was Jewish until the age of six, when her elementary school teacher insisted she attend Torah class. The strong-willed Hedy told the teacher she did not want to be Jewish. If she was required to have a religion, she preferred to be Catholic or Lutheran, like the other children. The teacher made it clear she had no say in the matter. Her parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and all the distant Wachenheimer relatives were Jewish. That meant she was Jewish as well.

Her anxiety grew as she cycled past a dentist’s office on the outskirts of Ettenheim. All the windows in the house had been smashed. The violence seemed inexplicable and arbitrary—no other house in the street had been attacked—but Hedy was sure it had something to do with the fact that the dentist was also Jewish.

Hedy parked her bike outside an imposing neoclassical building with the word gymnasium and 1875 inscribed across the entrance. Small groups of teachers and students were engaged in excited conversations. They glanced at her out of the corner of their eyes, but did not speak to her. She made her way as usual to her classroom on the second floor, overlooking the schoolyard. She was used to being treated like a pariah. During breaks, she would stand by herself on the front steps of the school while the other children played tag in the yard. Never invited to join their games, she was left with nothing to do but nervously finger a reddish-brown sandstone column until the break was over. After three years standing in the same spot, she had worn a small indentation in the stone.

Most of the teachers behaved correctly, if distantly, toward her. The exception was the math teacher, Hermann Herbstreith, a sergeant in the Nazi Party “protection squad,” or Schutzstaffel, known more familiarly as the SS. Herbstreith enjoyed humiliating his Jewish students. He came to class in a black SS uniform, with a revolver thrust into his right boot. When he asked Hedy a math question, he would gesture at the gun. Sometimes, he even pulled the revolver out of his boot and pointed it directly at Hedy, towering over his terrified, diminutive pupil. It did not matter how Hedy answered the question. As far as Herbstreith was concerned, her answers were always wrong.

“That’s a Jewish answer,” he would sneer, as her classmates snickered. “And we all know that Jewish answers are no good.”

Hedy dealt with the ostracism of her peers by focusing on her studies. She received top marks in all her subjects with the exception of math, which she failed repeatedly.

The Gymnasium was an elite secondary school, reserved for students with an excellent academic record. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, they had switched the emphasis from academic studies to “German studies,” including physical education and the glorious antecedents of the Third Reich. When Hedy’s parents first tried to enroll her in the school, back in 1935, she had been rejected as a non-Aryan. The principal, Walter Klein, made an exception for the young Jewish girl on the grounds that her father had fought for the Fatherland in the Great War, and had even been wounded in battle.

Classes started punctually at eight o’clock. On this particular day—Thursday, November 10, 1938—the moon-faced Dr. Klein entered Hedy’s classroom half an hour later. He made a speech, dictated to him earlier by the mayor, about the “justified wrath of the German people,” before pointing his finger directly at Hedy.

“Get out, you dirty Jew,” he screamed, his usually smiling face contorted with rage.

Hedy could not comprehend the transformation that had overcome the principal, a gentle man with a bald pate and trim mustache, in the space of a few seconds. Even though she had seen the broken windows of the Jewish dentist’s office, she found it difficult to grasp the reason for Dr. Klein’s anger. Previously, he had seemed well disposed to her and had even praised her “aptitude for languages.” She thought she was somehow at fault. Perhaps she had yawned in class, or failed to pay attention to one of her teachers. She worried about how to explain herself to her parents when she got home.

Mystified by what she had done wrong, and how she might make amends, Hedy asked the principal to repeat himself. He not only repeated the words

“Raus mit dir, du Dreckjude!” but grabbed her by the elbow and pushed her out the door. He then instructed the remaining students to join a demonstration against the Jews that was being organized outside the village hall. Minutes later, the students streamed out of the classroom, yelling “dirty Jew” as they rushed past Hedy, and headed up the street toward the Baroque town hall, the Rathaus.

Unsure what to do, Hedy crept back into the empty classroom. She sat down at her desk and took out a schoolbook. After a few minutes, there was a timid knock at the door. It was Hans Durlacher, also from Kippenheim, the only other Jewish student left in the school for the fall 1938 term. Hans was in the grade below Hedy. He told Hedy that the principal had screamed at him as well. He was frightened. Reluctantly, Hedy said he could stay with her as long as he did not disturb her studies.

Hans sat by the window overlooking the schoolyard and Adolf-Hitler-Strasse, the name given to the most important street in every German village. After an hour peering out the window, he beckoned urgently to Hedy to join him. Together, they watched SS men herd dozens of disheveled prisoners down the street with whips and sticks, shouting at them to go faster. The men and boys, some not much older than Hedy, were chained together at the ankles in rows of four. Bringing up the rear was a gang of hoodlums from the local furniture factory armed with chair legs that they used to smash the windows of Jewish homes. Draped around their necks were strings of sausages looted from a Jewish butcher.

The terrified students decided they should call home to find out what was happening. They went to a nearby store to find a telephone. When Hedy tried to reach her mother, a strange voice answered.

“Der Anschluss ist nicht mehr in Betrieb,” the voice announced. “The connection is no longer in operation.” Next she tried her father’s office and the Kippenheim home of her aunt. Everywhere the result was the same. “The connection is no longer in operation.” Hans got the same answer at his house.

The school day was not yet over but the building was deserted. Everybody else in the Gymnasium was either taking part in the demonstrations or had gone home in disgust. There was nothing for Hedy and Hans to do except go home themselves. When Hedy reached her apartment on Bahnhofstrasse, she noticed that the blue shutters on the second floor were closed. The front door was locked. This was odd, as her mother was normally at home during the day and always left the shutters open.

Hedy rang the doorbell but nobody answered. Trying to hold back her tears as she stood in front of the empty apartment, Hedy noticed one of the village’s most prominent Nazis walking down the street. Normally she would have done anything to avoid the man, who was notorious for his hostility to Jews, but she was desperate to find her parents. She crossed the street and asked the Nazi if he knew what had happened to her mother.

“I don’t know where the goddamn bitch is,” he snarled. “But if I find her, I will kill her.”

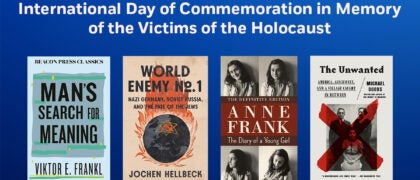

Copyright © 2019 by Michael Dobbs. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.