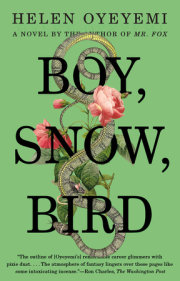

Harriet Lee’s gingerbread is not comfort food. There’s no nostalgia baked into it, no hearkening back to innocent indulgences and jolly times at nursery. It is not humble, nor is it dusty in the crumb.

If Harriet is courting you or is worried that you hate her, she’ll hand you a battered biscuit tin full of gingerbread, and then she’ll back away, nodding and smiling and asking that you return the tin whenever convenient. She doesn’t say she hopes you’ll enjoy it; you will enjoy it. You may think you don’t like gingerbread. Well . . . just try this. If you live low‑carb, she can make it with almond or coconut flour, and if you can’t have gluten, she’ll use buckwheat or millet flour, no problem.

A gingerbread addict once told Harriet that eating her gingerbread is like eating revenge. “It’s like noshing on the actual and anatomical heart of somebody who scarred your beloved and thought they’d got away with it,” the gingerbread addict said. “That heart, ground to ash and shot through with darts of heat, salt, spice, and sulfurous syrup, as if honey was measured out, set ablaze, and trickled through the dough along with the liquefied spoon. You are phenomenal. You’ve ruined my life forever. Thank you.”

“Thank you,” said Harriet.

She makes two kinds—the kind your teeth snap into shards and the kind your teeth sink into. Both are dark and heavy and look like they’ll give you a stomachache. So what? Food turns into a mess as soon as you chew it anyway. She sometimes tells people that she learned how to make the gingerbread by watching her mother and that the recipe is a family recipe. This is true, but it’s also edited for wholesomeness. Harriet’s mother, Margot, is no fan of gingerbread. She stood alone over her mixing bowl and stirred with the clenched fist of a pugilist.

Bambi‑eyed Harriet Araminta Lee seems so different from the gingerbread she makes. If she has an aura, it’s pastel‑colored. She’s thirty‑four years old, is always slightly overdressed, and wears hosiery gloves when pulling on her tights so as not to snag them. She has a slight Druhástranian accent that she downplays so as not to get exoticized, and she doesn’t like her smile. To be precise, she doesn’t like the way her smile photographs as forced. So smiling’s out. But she doesn’t think she can sustain a sober look without seeming unfriendly, so she frequently switches between two expressions—one she thinks of as Alert and the other she thinks of as Accommodating, though she’s the only one who can tell the difference. Since her name is far from uncommon, she’s encountered other Harriet Lees, Harriet Leighs, and Harriet Lis. Taken in aggregate, Harriet Leigh/Li/Lee is a hard nut, a pushover, thin‑skinned and refreshingly forthright, a hedonist and a disciplinarian. She’s met Harriet Lee who is a post office clerk by day and a stand‑up comedian at night, and she’s met Harriet Li the practicing psychoanalyst. She’s met Harriet Lee the Essex princess, Harriet Leigh the naval officer, and Harriet Li the sales assistant so rude that you make a note of her name so as to be able to tell the manager about her. The only thing our Harriet really feels she brings to the Harriet Li/ Leigh/Lee brand is a categorical sincerity. Her gingerbread keeps and keeps. It outlasts all daintier gifts. Flowers wilt and shed mottled petals, mold blooms greenish‑white on chocolate truffles, and Harriet’s gingerbread hunkers down in its tin, no more attractive than the day it arrived, but no more repellent either.

The gingerbread recipe came down through Harriet’s father’s side of the family. It was devised by a person who became Harriet Lee’s great‑great‑great‑grandmother by saving Harriet’s great‑great‑great‑ grandfather’s life. In their time there was a clemency clause for those about to be publicly executed. Before he made you climb up onto the beam, the hangman took one shot at matchmaking on your behalf. Will any take this dross to wed? or whatever it was they said in those days. Marriage was purgatorial, purifying. All it took was for one member of the crowd to come forward and say that they would handle your rehabilitation. This was rare, but it did happen. And then the two of you were married at once so neither party could think better of it later.

Many viewed public executions in moral terms, or in quasi‑cosmic terms, as a gesture toward some sort of equilibrium. Others approached them as spectacle, but due to the clemency clause, public executions occupied a space in Harriet’s great‑great‑great‑grandmother’s life not dissimilar to the blind dating and speed dating of today. Plenty of opportunity for a realist who has some idea of what she’s looking for. At the past five executions Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma’s gut had told her no. But this time, situated as close to the scaffold as she could get, she found herself standing next to somebody sobbing into a deluxe handkerchief, and she thought it was interesting that the woman kept dabbing her face even though not a tear fell. Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma also found it interesting that the woman kept making hand signals to the man about to be executed, signals the man returned with authentic tears. The ragged reprobate and the lady in silk. And as his list of offenses was read out, it seemed to her that, while brutality had been a near‑unavoidable by‑product, the motivation was money. Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma eyed the lady in silk, who was listening with downcast eyes and her handkerchief held up to conceal what must surely be a smile. Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma took another look at the ragged reprobate and bade him a silent farewell. She thought it something of a mercy for the gullible to die young, as being too often mistaken breaks the spirit.

But then, asked for his last words, Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandfather said he’d do it all again. His voice was so shaky he had to repeat himself a few times before anybody understood what he was saying. Could this man be any more terrible at lying? Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma put in her bid for him.

Family lore has it that they entertained each other very well, the pragmatist and the man who was almost too gullible to live. One had more patience, and the other had more resolve, and they were about even when it came to daring, so their love established possibilities and impossibilities without keeping score. They settled on caretaking a farm, raised grain crops for the farm’s owner, and lived very much at the mercy of a climate that would exhibit dazzling beneficence for three or four years in a row and then suddenly take back all its gifts, parching and flooding and freezing the land or reaching through the soil with a gray hand that strangled growth at the root. The abundance of a good harvest overwhelmed the family with glee and trepidation—it put a bone‑cracking temporal pressure on them, like raking in gold that rots. As for the lean years . . . Harriet’s great‑great‑greats shunned both prayer and provocation. They had talked it over, and nature struck them as an entity that was either cruel or mad. Not caring to attempt communication with it, they merely sought not to offend it. They kept having more children, so there were always about fifteen, including the ones on their way in or on their way out. The gingerbread recipe is one of the lean‑year recipes, and it stands out because the lean‑year recipes are all about minimizing waste and making that which is indigestible just about edible. None of it tastes good save the gingerbread, which is exactly as delicious as it has to be. Blighted rye was the family’s food of last resort, and the jeopardy in using it was so great that it made Great‑Great‑Great‑Grandma really think about how to take the edge off. Out came the precious ingredients, the warmth of cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, and ginger, the best saved for last. After this gingerbread you might sweat, swell, and suffer, shed limbs. Often that didn’t happen—often the strenuous sifting of the grain expelled just enough ergot to make this an ordinary meal as opposed to a last meal. But just in case, just in case, gingerbread made the difference between choking down risk and swallowing it gladly.

That temporary subtraction of fear still gives Harriet’s mother goose bumps. It is a veiling of alternatives, a way of making sure you don’t reject the choice Mother’s made for you. No matter what, you will not starve. She has a hunch that over the years, usage of this recipe has always fallen on the shadow side of things. In her own time, Margot Lee replaced the roulette rye flour with flour from wheat blighted by weather and worm. Nothing that would make anybody sick, just inferior grain that couldn’t be sold in the usual way. And Margot never did sell the gingerbread, though it brought her useful things through barter. Information, goodwill, and yes, on at least one occasion, compliance. Gingerbread was all she had to offer in exchange for these things, and all she had to spare.

Copyright © 2019 by Helen Oyeyemi. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.