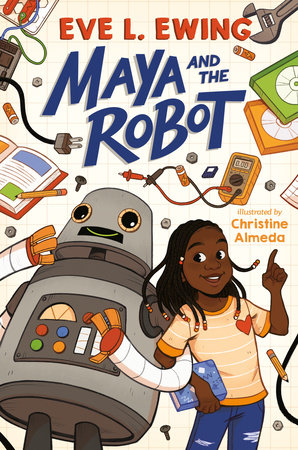

Chapter 1:

The Worst Science Fair Ever

If you looked outside through the cafeteria windows, it seemed like a perfectly normal day. The sun was shining. Birds were chirping. A regular day. A beautiful day, even. But inside the cafeteria, things were anything but normal. All around me, kids and adults were screaming. I tried to shut out the chaos for a second and focus on the sunlight. Just breathe, I told myself. Count your breaths. Calm down. One . . . two . . .

“Yaaaaarghhhh!” came the ear-piercing yell from behind me. “My computer is covered in pudding! Pudding!”

I spun around to see Zoe Winters, the most popular girl in my class, standing in front of a display table where her science fair project had once stood. When I had walked into the cafeteria carrying my own project, I’d noticed how neat the whole thing was—the letters that spelled the project title, “Coding and Circuits,” across the top of the board, the computer and circuits and batteries set up in a display at the front of the table.

Now it was a mess that mostly resembled a pudding waterfall. Pudding dripped over the title, smeared across the letters so it said COD CIRCU S. Pudding filled the keys of the computer keyboard. But I really cringed when I saw something even worse than ruining an expensive computer. Zoe hadn’t noticed yet, but there was also—

“PUDDING IN MY HAIR! CHOCOLATE PUDDING IN MY HAIR!”

Okay. I guess she had noticed. Brown, thick, fudgy droplets cascaded from Zoe’s once-perfect curls into her eyes, and she stopped saying words and started making horrible gurgly sounds. “Ayyyaaazzzrrrruuuuggghhhmaaargh!”

I was going to go over and help her when a streak of something yellow flew past my ear. I looked behind me to see that it was creamed corn. It had been launched with the accuracy of a fastball, landing dead center in a huddle of screeching first graders. They were sheltering in the corner with their teacher, screeching and giggling at the pudding waterfall, but now that it was raining corn, they started panicking and running in circles, except for one kid who must have been hungry, because he started trying to catch the bits of flying corn with his mouth.

“Mommy, I don’t like corn!” wailed a kindergartner. She took off running at top speed to try to get as far away from the corn hurricane as possible. “No, stop!” I yelled after her, but it was too late. She skidded on a gross mixture of pudding and corn that was waiting on the floor like a cartoon banana peel, her light-up gym shoes slipping and sliding as she struggled to stay upright. Desperate, she grabbed the nearest solid piece of furniture—the corner of the display table where my best friend Jada was trying to guard the scale model she had built of a suspension bridge. It was a work of art. I could tell Jada must have fussed over it for weeks—it wasn’t any old thing she made out of a kit. There were LEGOs and toothpicks, tiny wires, plastic beads, Popsicle sticks, and even a tiny glowing LED light at the top of the bridge. It was complex and beautiful. The little kid grabbed the table, and Jada froze, seeing her creation in danger but not knowing what to do. She couldn’t push a younger kid out of the way, but I could see by the pain in her face that she was strongly considering it. “Noooooo!” a voice screamed, and when they both turned their eyes on me I realized that the voice was mine.

Have you ever seen one of those videos that shows an avalanche coming down a mountain in slow motion? Imagine that, but replace the snow with LEGOs and toothpicks and beads, and you’ll see what I saw as Jada’s project came tumbling down onto the small girl sitting pitifully on the floor in a puddle of pudding.

Jada stood there, arms hanging at her sides, and watched it happen. For a second she seemed to be in shock. Then she took a deep breath, furrowed her brow, and hollered at the top of her lungs: “THIS! IS THE WORST! SCIENCE FAIR! EVERRRR!” And then she began to cry. First her voice, then her sobs, reverberated around the room, but no one seemed to hear her. Everyone was too busy trying to handle the disaster that was unfolding.

The gym teacher was blowing his whistle for order. But it stopped making any sound when a blob of mashed potatoes flew into his face. He kept blowing, but the whistle only shot out white specks of mashed potatoes with every breath. Ms. Hixon, the cafeteria lady, had transformed into some kind of acrobatic martial artist, leaping from table to table, slapping flying food projectiles out of the air with a huge metal spoon. “You think this is my first food fight? This ain’t my first food fight!” she yelled at no one. In one corner, there was so much creamed corn spilled on the floor that it made a pond large enough for several preschool kids to be sitting in it and having the time of their lives, putting it in each other’s hair and throwing it at each other and grinning like it was a playground sandbox. Near the door, Mr. Samuels, the custodian, was standing forlornly with a bucket, shaking his head. “Nope,” he said over and over. “Nope, nope, nope. No way. I’m gonna need a bigger mop.” Pudding and mashed potatoes and corn were on everything. On the tables, the floors, the walls, in people’s hair. Pudding was splattered on the windows. People were digging mashed potatoes out of their ears and wiping it off their glasses.

And smack dab in the middle of the mayhem, there he was. Whirling in circles at top speed, scooping food out of industrial-sized vats and launching it in every direction. Beeping at a terrible high pitch, flashing multicolored lights, and appearing perfectly willing to spend the whole rest of the day tossing potatoes at people with no sign of stopping. This calamity, the screaming, the mess, the ruined science fair . . . this was his fault.

No, I realized. This was my fault.

After all, he was my robot.

My spinning, beeping, flashing, food-catapulting, going-completely-berserk-in-the-school-cafeteria robot.

Right on cue, I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned around to see Principal Merriweather. She was scowling. I gulped.

“You, my dear, are in big, big trouble,” she said. I opened my mouth to respond, but before I could speak, a glob of pudding hit me right in the middle of my forehead.

I guess I kind of deserved that. And I found out that getting hit in the head with projectile pudding is more painful than it looks.

How did I get here? I didn’t wake up, hop out of bed, and say, “I want to be a troublemaker kid who brings a robot to school and stands by doing nothing while it goes bonkers in the cafeteria, starts a creamed corn apocalypse, ruins the science fair, and makes my best friend cry.” Definitely not my goal. I swear, I’m really a regular person. And at the moment, a regular person who is probably about to get suspended, unless for some reason the principal enjoys wearing a pile of mashed potatoes as a hat.

Well . . . I’m a mostly regular person. A regular person with a robot.

But it wasn’t always that way. If the year had gone how I’d wanted it to, I probably wouldn’t have a robot at all.

It all started on the first day of school.

Copyright © 2021 by Eve L. Ewing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.