Now I have to pay attention, thought Jonathan. Now.

It’s starting now. He laid his trembling hands on his lap

and rubbed the middle of his left thumb with his right in the

hope that it would calm him down. It was his last morning in

jail. Like always, he was alone in his cell. The cell the others,

the guards, called his room. He was sitting on the bed waiting,

staring at the wall. He didn’t know what time it was. It was

early, he knew that much. The first strip of sunlight had just

forced its way through the split in the too-thin curtains. Halffive,

maybe six o’clock. It didn’t make any difference to him

today. I’ve got time, he thought. From now on I’ve got plenty

of time. They’ll come when they come. When they think it’s

the right time, they’ll come. I can’t do anything about that. No

earlier, no later. I’ll see.

Until they came he would watch the morning light push

further into his cell and slowly, imperturbably, move across the

walls in its own orbit, ignoring everybody. It had been ages

since he’d known exactly what time it was. The first night here

he’d immediately fiddled the batteries out of the wall clock. He

couldn’t stand the ticking. Plus the clock didn’t tell him anything

that was any use to him. Day activities weren’t compulsory and

he didn’t sign up for any of them. Walking in circles, education,

sport. Work. If you didn’t smoke, eat sweets or buy expensive

clothes, you didn’t need any money here.

He preferred to watch the position of the sun, the fullness

of the light, the way it caught the clouds drifting over the

watchtowers. That told him how much longer it was going to

last, how long till dark. How much longer he’d have to put up

with the racket: men’s voices creeping up from the exercise

yard, music through the walls. Shadows across the floor of his

cell, across the bed and the small table. But now it was going

to be different. “Everything will be different,” he whispered.

He waited. It was still quiet outside. After a while he stood

up, walked from the bed to his table, from the table to the

window, stood there for a moment and went back to his bed.

He sat down again, knees creaking quietly, then stood up once

more. He paused in the middle of his cell, then went back

to the table and looked down at it. On it were his therapy

workbook, his exercise book, pencils and pens. The bookmark

his mother had sent him. He sat down at the table again,

his back straight, and opened the exercise book. A beautiful,

blank page. He used both hands to smooth it out, arranged

it in the exact middle of the table, unscrewed the lid of his

pen and thought for a moment. After what seemed like ages it

turned out he couldn’t think of anything sensible to write. He

nibbled at the inside of his cheek. Why not? Why should he

run dry today?

He stood up again and clenched his fists. Walked from his

table to the window, from the window to the table and back

again. He sat down on the chair. “Nothing,” he wrote. And then,

“Never.” Followed by, “No!” He banged the exercise book shut.

The rest would come tonight when he was back home. He’d do

the next therapy assignment then. A little later he opened the

exercise book again, stared at what he’d written and crossed it

out. “Different,” he wrote beneath it, then drew a line through

that too. “Better.”

He rolled up the exercise book, picked up his pens and pencils

one at a time and put them in his pencil case, and slipped the

workbook into his bag with the rest. Then he sat down on the

bed, hands trembling on his lap, and waited for the moment

when the guard would unlock the door.

Now I have to pay attention, thought Jonathan. Now. It’s starting

now. He was sitting next to the last window, at the back of

the bus to the village. There weren’t any other passengers, but

he’d still walked past the empty seats. There was quite a bit of

morning left to go: the sun was still rising, but it was already

terribly hot. A drop slid out from his hair, slowly, down his neck.

All the way to the small of his back. He shifted on the seat. He

had his bag on his lap, holding it close. He was sweating under

his arms too. The bag was heavy on his knees. He would have

preferred to put it down on the floor, but somehow it seemed

safer like this, his fingers tightly intertwined. He sighed.

Between him and the world was the glass and behind the

glass the coastal landscape. The most beautiful country he knew.

The place where he had crawled out of his mother’s womb on

a nondescript Sunday morning some thirty years ago. A place

he would never leave. He looked at the landscape with brandnew

eyes. Not a single detail escaped him. He saw the tops of

the pine trees and the way the sun was very precisely spotlighting

the last row of sandhills, the grass on the side of the road

and the water of the small pools in the distance. The light slid

along the road with the bus, heating the asphalt. It was so hot

it wouldn’t have surprised him to see the tar bursting open in

front of him, starting to crack and melting from the inside out.

Soft, sticky lumps like mud on the soles of his shoes.

He closed his eyes for a moment, reopened them and looked

at the sky again. The light was almost painful, such a glaring

white.

Past the water tower, the bus curved off and down to the

right before slowly climbing again after the next bend. He

knew it all by heart, able to predict every twist and bump in

the road. Just a couple of minutes to the harbour, he thought,

and then the village. He could smell the slight stink of the sea

air through the open roof hatch. Fish, oil, decay, seaweed.

Rope.

This afternoon he would be out walking in these dunes,

maybe within an hour. At last. People didn’t like him; they never

had. But nature accepted him as he was. He squeezed one hand

with the other, held it like that, then stretched the fingers one at

a time until he heard the knuckles crack. His mother would be

home waiting for him. Sitting on the sofa, where else, watching

morning TV. He could almost hear the sound of the set that

had been about to give up the ghost for years now. All those

nights sitting next to her on his regular chair, the smell of the

dog in the room. Her hands clasped together and resting just

under her bosom. Often he’d be reading

Nature magazine but

unable to keep his mind on the words, the TV voices stabbing

into his thoughts. Then he’d let the magazine slip down to his

lap and watch her watch TV.

He thought about the little things, the things he knew so

well. The way the fingers of her right hand curled together and

slowly, absently reached for the thin chain of her necklace, the

way she took the silver cross between thumb and index finger

and began to rub it. That meant that something on TV had

aroused her interest and she was about to draw his attention to

it. The way she let the rosary beads glide through her fingers

when she was praying at night.

His hands were clammy. He felt the warmth of the engine

rumbling away inside the bus. Now and then he looked at his

nails, tugging at little bits of skin. Sometimes he raised himself

up slightly to get a better look into the distance, squinting against

the glare, then sitting down again.

He watched the seagulls gliding through the sky with their

beaks open. Sometimes they hung motionless for a moment as

if frozen in place. He thought of the birds whose flight he had

watched through his cell window. As long as he could. The

powerful beating of their wings. When they sailed past close

to his window, he imagined he could hear the wind whooshing

across their quills. In the back of his exercise book he kept a

list of unusual birds. Kittiwake gulls, lesser black-backed gulls,

fulmars, a guillemot. Tallying them gave him some peace of

mind amid the racket, the endless suffocation. It was unbearable.

Especially the proximity of all those men. The nauseating

smell of food.

But it was over now, as suddenly as it had begun. Despite

everything it had felt sudden. Last week was the umpteenth

hearing: the whole day in the docks, his lawyer’s words going

straight over his head like always.

And yesterday afternoon the official letter from the court

arrived. He had been acquitted on appeal. After all. Despite his

worst fears. That cancelled out everything: the prison sentence,

the therapy, the psychiatric hospital. There wasn’t enough

evidence. They hadn’t been able to find the T-shirt on which,

in the words of the prosecutor, incriminating traces could be

found according to the victim’s statements. “The prosecution

can still appeal,” his lawyer explained, “but I don’t expect

them to.” The case would only be reopened if they could dig

up some more evidence. But that was anyone’s guess. For the

time being he was free.

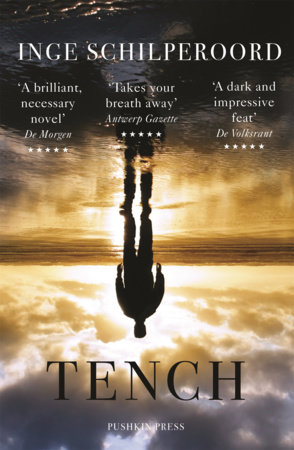

Copyright © 2018 by Inge Schilperoord. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.