1

A Forgotten Planet

When at last he opened his eyes, it was because he was falling. That meant he wasn’t dead, not yet. The earth below Giovanni was like cinder, slick from an overnight mist and steep as a windswept dune. With each "inch of his body the slope loosed beneath him— a hiss of shale, a rush of gravel— propelling him downward.

A ribbon of lavender broke the darkness, revealing the day’s first glimpse of La Rumorosa, the coil of borderland highway that writhes around the Sierra de Juárez, halfway between Tijuana and Mexicali. The gusts that moan through the rusted canyons and granite crags have given La Rumorosa its name: the Whispering Woman. In the span of fourteen miles, Carretera 2D

twists more than seventy times, corkscrewing as it plunges four thousand feet from shrouded mountaintop to swirling sands. La Rumorosa is a gash in the Baja desert, a white-knuckle trek and a dumping ground. Mythologized in ghost stories and second-guessed by safety engineers, the passage stirs primordial awe—a “forgotten planet,” the Mexican poet Adolfo Sagastume calls

La Rumorosa, a “silent uterus.” A city boy, Los Angeles born, Giovanni had never heard of the place. Now it was swallowing him.

Flailing his arms, pawing at dust, Giovanni felt the scrape of chaparral. He wrapped a hand around a gnarled root. It broke his slide. For a moment he was suspended, the cliff still once more. Blinking away the fog, Giovanni tried to make out the road above him; too high to see. Below, the gorge looked bottomless. He realized then that his shoes were gone, the black-suede Jor-

dans he’d bought with the check from his first honest job. Only socks covered his feet. He stared at his shirt, a white tee with the curly Sean John logo, now stained with vomit. Blood, too, had soiled the cotton. His neck throbbed, so much he could barely turn his head. The skin burned. He thought maybe he’d been shot, until he touched a finger to his throat. A collar of torn "esh, pulpy and raw, branded his windpipe. That was where the rope had seared him, where his killers, before tossing him over the edge, had cinched it tight, yanking like some soul-snatching repo men.

Now he remembered.

Giovanni rolled onto his elbows. His chest heaved. Tears stung his eyes. He tried to replay the previous night, to piece together the whole disastrous week. He was barely eighteen, but in just a few days of 2007, he’d lived a lifetime, from duress to euphoria to revulsion to catharsis, and finally betrayal. He’d been given a jale, a real heavy job. A test of his callousness and credulity. If he had the stomach for it—for dirtying himself in the name of an enterprise that "outed all checks on its power—he might at last earn the one thing he craved: respect. It was an easier word to say than love. If he backed out, he’d confirm every doubt and suspicion. Giovanni didn’t stop to question why he’d been selected, what made him the right candidate for such a foul mission. The

minute they’d put the .22 in his hand on a crowded LA sidewalk, he had no choice but to step up—to prove himself worthy. And then he’d gone and botched it.

News crews were now doing live shots from that same stretch of blood-splattered pavement. Pastors were leading vigils. The Los Angeles Police Department’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division was combing the neighborhood. The most nefarious prison mafia in America was demanding a scapegoat. The city was dangling a $75,000 reward for information leading to the capture

of the suspect—“a threat to everyone,” the mayor declared, “everywhere.”

Hiding out in Mexico hadn’t been Giovanni’s idea, but he’d embraced the melodrama of a run for the border. He was a desperado blending into the jangle of Avenida Revolución, losing himself in a TJ blur of clubs, strippers, booze. In a few months, the heat off him, his penance complete, Giovanni expected to make his return: back to the girl from Subway with the irresistible dimples, whose name he’d inked that summer across his right hand; back to his mom, a janitor at the mall, whose despondence he’d both fueled and fled; and back, if all went well, to his tribe of bald-headed soldiers and slangers, the outlaw capitalists of MacArthur Park, who offered an identity more conse- quential, more urgent, than the routines of a neighborhood whose sweat kept the city scrubbed and fed and prosperous.

Don’t die, he told himself.

Don’t die like this.Giovanni had a baby face, even with a pencil’s width of fuzz clinging to his upper lip. His grin began sly but soon grew plentiful, and his eyebrows formed twin arches that seemed to scout for approval. Built like a flyweight, all clavicles and ribs, he’d been fidgety for as long as anyone could remember, a rat-a-tat of bouncing knees and rubbing hands. His first-grade teacher noted that Giovanni “needs to learn to stay on task and work cooperatively.” His third-grade teacher predicted that Giovanni “could be outstanding if he were more serious and less distractable.” His fifth-grade teacher found Giovanni “so restless he seldom #nishes an assignment.”

Giovanni’s first great passion was

Street Fighter, the arcade game, which he played at a mini-mall donut shop with quarters filched from his mom’s change jar. He favored the role of Akuma—orange hair tied in a topknot, sculpted arms bursting from shredded sleeves—whose signature move

resembles an act of frustration. Rearing back, the fighter slams his fist down to the earth, a godlike blow that unleashes a lethal shock wave.

In middle school, Giovanni signed up for a different kind of martial experience, a National Guard youth contingent called the California Cadet Corps. He’d started seventh grade the week before 9/11, and with Americans rushing to enlist, he sensed a shared purpose in the program’s starch and creases, a narrative that offered strength and stability. He learned to polish his shoes and center his garrison cap. He marched, heel-first, in formation, pivoting to the column and flank commands, and saluted his major with sharp karate chops to the brow. He wished he’d volunteered for the riffe drills, to learn to port and present arms with one of those triggerless wooden parade models, but he’d been too nervous—afraid of an embarrassing bobble or a breach of some protocol he’d failed to consider. If he’d been asked then what he planned to do with his life, Giovanni wouldn’t have hesitated: join the army. He wanted to belong to something that mattered.

Giovanni’s dad, a sad-faced man from Guatemala, seesawed between sentimentality and affliction. Juan washed dishes and buffed floors and knocked down walls for a demolition crew. Despite five DUIs, he also valeted cars at a Hollywood club; he carried a picture of himself with Jean-Claude

Van Damme from the time the action hero handed him the keys. Before his borracheras blew up the family, before Giovanni’s mom reached for a kitchen knife to silence his rants, Juan had done what he could to guide Giovanni and channel his excitability. He gave his son a pit bull they called Rocky, and together they built a doghouse in their backyard. He strung a sand-filled punching bag from a tree out there too, encouraging Giovanni to pummel it until his arms grew limp. To bulk him up on the cheap, Juan fed Giovanni 99-cent Whoppers, MacGyvering the burgers by slipping a fried egg between the buns.

As the eldest of three kids—he had a brother a year younger and a sister born six years after that—Giovanni took the brunt of Juan’s disappointments, reminding his jefito of his own interrupted dreams. In those moments of shame and frustration, Juan resorted to the old-country discipline he’d been raised on in the mining province of Chiquimula. He’d dump uncooked rice

on the kitchen floor and force Giovanni to kneel, bare-legged, until it felt like fire ants were burrowing into his skin.

It was only by accident that Giovanni learned his dad was his stepdad. Not even the difference in their last names had tipped him off. His mom’s last name didn’t match his or Juan’s; Giovanni assumed everyone could just choose their own. He was thirteen when it happened: rooting in a bedroom closet for Juan’s trove of VHS porn, Giovanni stumbled on a family photo

album. For the first time he saw pictures of another man, a proud father showing off a newborn, and felt a pang of recognition. Mystery dad looked like a swashbuckler—Ray-Bans, acid-washed jeans, ’77 Olds—and in his taut gaze Giovanni glimpsed a stolen past, a stunted future.

The discovery confused and then enraged Giovanni, leaving him with the sense he’d ingested a toxin:

What other lies had he been fed? His mom, Reyna, begged him to understand. She had been so young—a runaway—pregnant at seventeen, and again at eighteen with his brother. She had meant to tell him once he was old enough, but she’d never found the right time or words. It was

a story she wanted to forget, anyway, to bury along with the man in the picture. The explanation she offered her son—that his biological father had fallen ill when Giovanni was barely a year old, that the doctors had given him just months to live, that he had left her and the boys in LA so he could return to Mexico to die—was only partially true.

With adolescence came the freedom of skating: a license to turn obstacles into exploits. Giovanni pored over the California Cheap Skates catalog, a universe of coastal-cool regalia that promised style and status, even if Reyna’s paycheck couldn’t possibly stretch that far. His first board, a Darkstar, came to him hot. A dude rolled by in a van, asked Giovanni if he liked to skate, and

fobbed it off on him for $20. What Giovanni coveted most were Chad Muska shoes. The San Diego freestyler had a scraggy, fearless aesthetic, blond mane flopping as he nose-slid down handrails cradling a boom box. Thee sneakers featured a Velcro compartment—a stash built into the tongue. By the time his mom scraped together the cash to award him a pair, Giovanni had caught

on to the design. He ollied through the hood in pegleg jeans, hair gelled and spiked, Chili Peppers and Metallica on his headphones, and yerba squirreled away under his laces.

Smoking weed made Giovanni’s heart race and his throat tighten. He was fourteen the first time he panicked. His mom took him to Children’s Hospital in East Hollywood, but the EKGs and X-rays showed nothing. Three weeks later he was back in the ER complaining of dizziness and chest pain—and then four more times over the next two months. His mom feared something catastrophic. The doctors diagnosed anxiety and depression, instructing Giovanni to “take deep slow breaths and think of pleasant thoughts.”

As a child, Reyna had been cast north by El Salvador’s civil war and secreted across the border in the trunk of a sedan. It was an uprooting she never quite recovered from, a tale of movement and survival that instead of offering hope left her feeling out of step. She wore her hair in bangs and

applied her eyeliner in feline swoops. She’d worked as a housekeeper and a hotel maid and a server at a late-night pretzel stand. Her Spanish was snappy and insistent, but when she switched to English, her voice grew softer and warier, as if every word were a question. Unlike most of the men in her life, Reyna was not a drinker; she preferred McDonald’s coffee, cut with four sugars and four creamers. There were sorrows she didn’t know how to drown.

One morning in 2004, not long after Giovanni started high school, he poked his head into his mom’s bedroom. In his younger years, he’d creep and then pounce, waking Reyna with a belly flop; she’d muss his hair and call him mono. Her little monkey. This time he found her under the covers, trembling, a bundle of whimpers and wails. “What the—,” he blurted. Then he saw the

mess of pills. He knew he hadn’t done much to make her life easier, but Giovanni couldn’t imagine that his own mom would no longer have it in her to raise her children, to muster worries, to dispense reprimands. He dialed 911. The operator told him to keep her awake until paramedics arrived. Giovanni shook his mom. He begged her to open her eyes, demanded she not

leave him. Reyna arrived at Good Samaritan sobbing. She confessed that she’d been popping ibuprofens for the past day and a half—an overdose of Motrin—maybe sixty-five in all. “I don’t want to be in this world anymore,” she told the doctors. On her chart, they wrote: “family problems.” Giovanni would always remember how he felt at that moment, as if the earth were spinning too fast to hold him in place. He had saved his mom. He was losing his way. It was Giovanni’s fifteenth birthday.

As the sun inched higher, rousing the lizards from their blanched hideouts and stirring the quail that grub seeds in La Rumorosa’s brush, Giovanni saw that he was alone. Nobody was watching to make sure he’d died. Nobody was around to offer help. If he couldn’t scratch his way up, nobody would ever spot him hugging the cliff, not until it was too late. Giovanni dug his feet into the sediment. He lunged and clawed. His neck screamed. The cliff held. Giovanni did it again, squirming faster, reaching higher. He’d been disposed of, and now he’d awoken. Carretera Federal 2D was just above him. He didn’t know where he was going or how to get there or what he would do if he made it. He just knew he had to pull himself out, to rise from this woeful tomb.

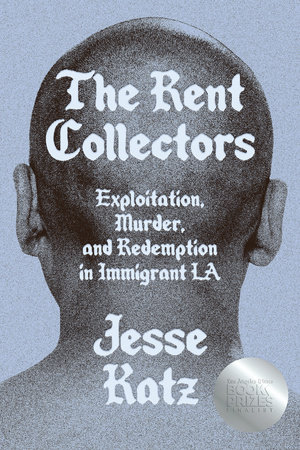

Copyright © 2025 by Jesse Katz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.