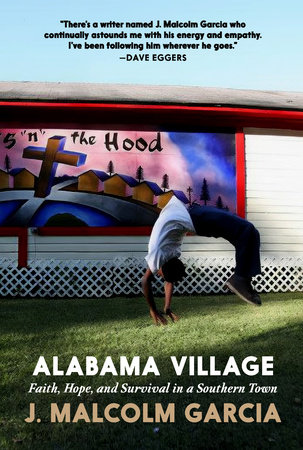

Overture

December 2020. A friend calls and tells me about a feature story he saw on PBS about this neighborhood called Alabama Village. It is one of the most violent places in the country, the broadcast said. The show compared its strife to the civil war in Syria. When I lived in Illinois, people called Chicago Chiraq, because of its astronomical homicide rate—as many as forty shootings on some weekends. But that was Chicago. It was hard to believe that an obscure neighborhood in an equally obscure small Southern town would in its own way be as bad as Chicago, let alone the Syrian civil war.

I search the internet for more information. Prichard, a predominantly Black city of 19,322, according to the 2020 census, is among the poorest in Alabama, with a median household income of just over $36,000 and more than 30 percent of its population below the poverty level.

Prichard was incorporated in 1925, about five miles south of Mobile, and industrial development fueled growth in the city in the decades that followed. The community of Alabama Village was a war housing project within Prichard developed in 1942 for shipbuilders working in and around Mobile. Single-story homes, similar in appearance to enlisted housing on a military base, lined its streets, which were named after Alabama counties.

Following the war, the residences became available for private purchase; many of the workers from the nearby paper mills and shipyards bought homes here, and the white population in Prichard soared to about forty-seven thousand by 1960. Alabama Village thrived as a typical blue-collar community, offering permanent homes for many low-income families throughout the 1950s and ’60s.

Property values began falling in the 1980s and crime began to rise, changes that coincided with white flight and the rise to power of Black politicians. By the 1990s, there were only a handful of families who owned and physically lived in their homes in the Village. Many property owners rented out their houses. Over time, however, collecting rent became difficult, and in some cases dangerous. Unable to sell, many landlords chose to abandon their property. The majority of them made their residences available for government-subsidized housing. Prichard suffered from declining tax revenues as businesses closed or moved. Between 1970 and 2014, the population declined 48 percent. The city’s finances were depleted to such a point that in 2012, according to the

New York Times, Prichard became the first municipality in the United States to stop making pension payments to retired city workers.

Crime continued to grow. In 2008, Prichard was listed as the eighth most dangerous city in the United States. The city’s violent crime rate from 2001 to 2008 was higher than the state and national levels. From 2009 to 2012, the violent crime rate increased to 400 percent of the state and national rates. In 2013, the city of Chickasaw, which shares a border with Prichard, erected barricades across Iroquois Street, which used to link The Avenues, a working-class Chickasaw neighborhood, with Alabama Village.

Political corruption added to these problems. In 2019, former Prichard City Clerk Kim Green was accused of stealing more than $400,000 while working for the cities of Creola and Prichard. Prosecutors put Prichard’s loss at $158,449. Mayor Jimmie Gardner said the city was blindsided by her guilty plea.

One year later, a judge sentenced James A. Blackman, a former chief of staff of Gardner’s, for pocketing about $200,000 from Prichard between January and December 2017.

Predictably, city services suffered from neglect. Fire protection has been hobbled by low and undependable water pressure. In 2018, 93 percent of Prichard’s fire hydrants failed an inspection. The Alabama Department of Environmental Management describes Prichard’s water lines as being in dire need of repair.

With so many problems facing Prichard, the Village’s predicaments festered. About forty-two families live in the Village today. City services barely exist. In the Village, about a million gallons of water once supplied to homes and businesses drains out of decaying pipes every year. The few remaining streets flood for days after a heavy rain because of the drinking water that collects in the storm sewers.

The Village may not be Syria, but its desolation and violence shocked me. I had been a social worker for fourteen years helping homeless people in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. They turned empty buildings into crash pads and crack houses. The hovels I had seen made me nauseous, but what I saw in the Village was on a scale beyond anything I’d ever experienced.

I made the jump into journalism at forty and devoted myself to covering families like my former homeless clients, people who live well below the news radar, and if in the unlikely or unfortunate event they become noteworthy, are generally viewed with disdain. The residents of the Village fell into that category.

I wonder about John and Dolores Eads. What is their motivation? As a social worker, I worked with religious people and found they did not stick around long when their prayers went unanswered. Too often they suggested the homeless men and women I worked with didn’t have faith. John and Dolores, however, had stuck with it for twenty years. Surely, they’ve suffered disappointment. Surely, some of their prayers have gone unanswered. But they stayed. They had to be more than do-good Jesus people.

I call John on a Wednesday morning. Totally cool, he says when I tell him I want to write about the Village. I give him a little of my social services background, how my agency had to endure state budget battles and budget cuts. That’s screwed, he says. Sounds like it sucked. Total crap. We don’t accept government funding. He does not ask if I’m saved, as have other Christians I’ve met. He doesn’t go there. I’m a stranger on the phone interested in his work. Nothing more, nothing less.

He explains that he and Dolores do not restrict themselves to a denomination. When they started Light of the Village, John wondered if he should study theology but a pastor at a Baptist church he attended in Mobile dissuaded him. For what God has called on you to do, do you think the kids care about a degree? No, John said. That settled it. John considers himself a layperson who practices his faith. If someone had to put a finger on it, he would say that he and Dolores are evangelicals. They take the Bible and go verse by verse, story by story, allowing it to speak for itself. They do not push it. They do not cram it. Anyone can come to the ministry. It offers free afterschool programs, meals, and Bible study. Faith or lack of it has no bearing on who can participate.

I’m not selling a product, John tells me.

If I want to visit the Village, I’m more than welcome. He suggests people I should meet, including a guy he calls “Bigg Man.” He’s deep in the street but has good insight, John says. We’ve known him for years.

A magazine editor I know is enthusiastic about a story on the Village so in late February 2021, I throw my duffel bag into my car and leave my San Diego home for Alabama

Copyright © 2025 by J. Malcolm Garcia. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.